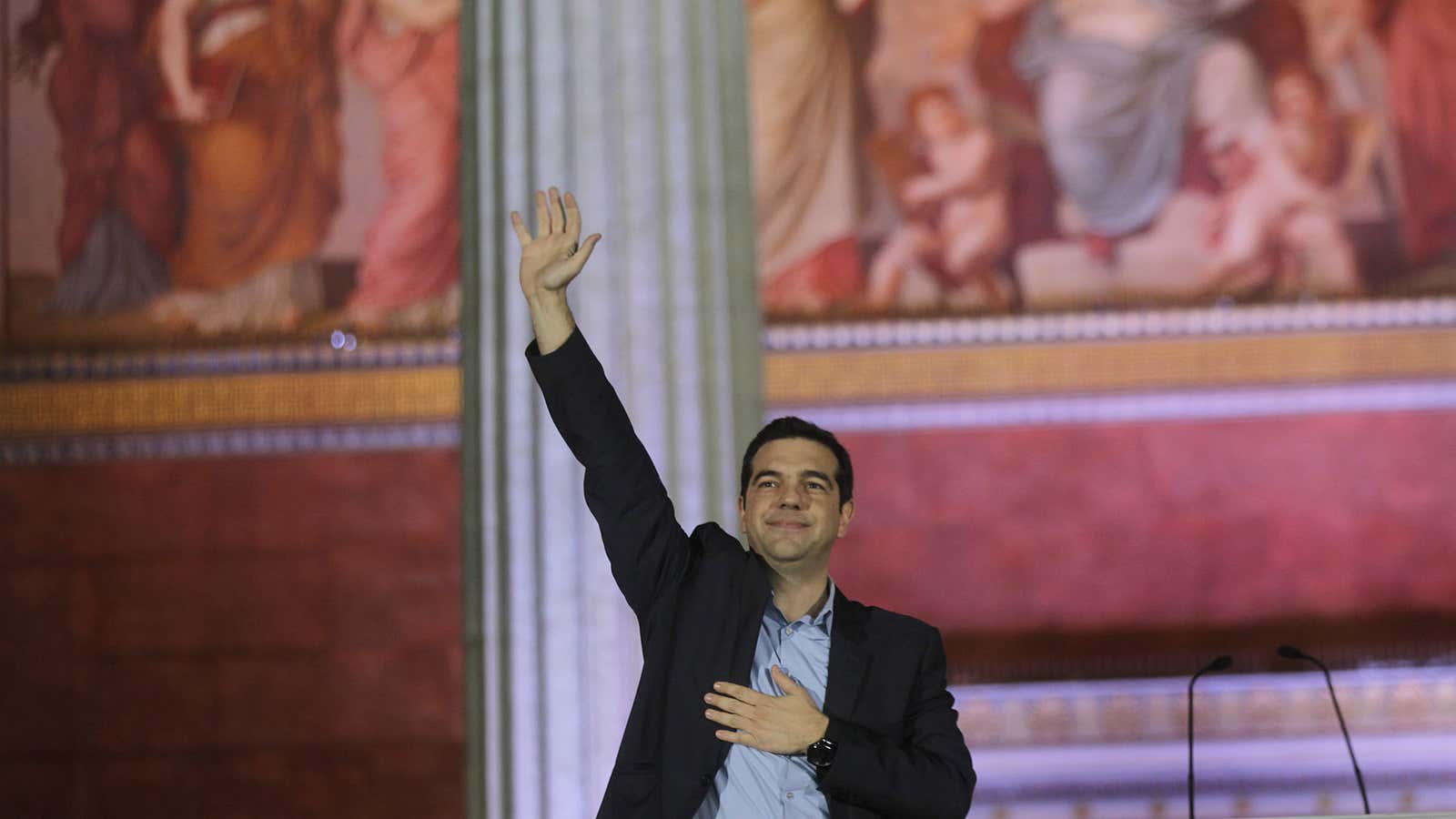

Last month, Greek prime minister Alexis Tsipras nearly derailed a new bailout for Greece by calling a national referendum on the rescue’s proposed terms. In the end, voters rejected the measures, but Tsipras was forced to agree to creditors’ harsh conditions anyway.

Now, voters are set to go to the polls again, this time for a general election next month. Tsipras, who was elected in late January, has resigned in order to trigger a snap election, as he seeks to solidify his power by ejecting rebels from his own party, Syriza.

“The people will have to decide again,” he said in a televised address. “You will have to decide whether we represented you with courage… We have done everything in our power to save Greece.”

European markets are showing their usual jitters at the prospect of yet more instability in Athens. At least this time the prime minister waited until the bailout deal was done, if only just: Greece got its first dollop of aid from the €86 billion ($96 billion) bailout deal today (Aug. 20).

Like the previous poll, this vote will change little. In essence, Greeks will be deciding who they want to implement the conditions that are already spelled out in the country’s latest bailout deal. Creditors have shown little appetite for compromise, leaving whatever government emerges from the election with no room for maneuvering.

To recap: Syriza rose to power by campaigning against the austerity required for a new bailout deal. It later campaigned against the terms of said bailout deal in a referendum, which it won. It will now have to campaign on its record of signing and implementing a rescue deal that it first pledged to scrap and then fought to reject.

Nevertheless, Tsipras remains popular and Greeks generally support the bailout as the price of staying in the euro zone. Wrenching reforms and painful austerity are unpopular, of course, but if the naysaying hard-left faction of Syriza decides to split from the party, it is not clear that it can become a meaningful force in parliament on its own.

In recent weeks, around a third of Syriza’s 149 MPs in the 300-member chamber have defied their prime minister in successive parliamentary votes on terms demanded by Greece’s creditors. Tsipras is betting that he can swap out these rebels for more amenable allies, and maybe even take some seats from the fractious and disunited opposition to win an outright Syriza majority, instead of being forced into another coalition government with an outside party.

The biggest risk is that in the run-up to the vote, all of the momentum and goodwill that Greece has won from creditors—crucial if Athens is to win much-needed debt relief down the road—will erode. A caretaker administration led by a judge can hardly be expected to implement far-ranging reforms and pass complex budgets while the politicians are out on the campaign trail. The deadlines set by creditors to pass laws and hit targets could slip, but frankly—what else is new?