We know China is big. By some measures, China is now a bigger chunk of the global economy than the US.

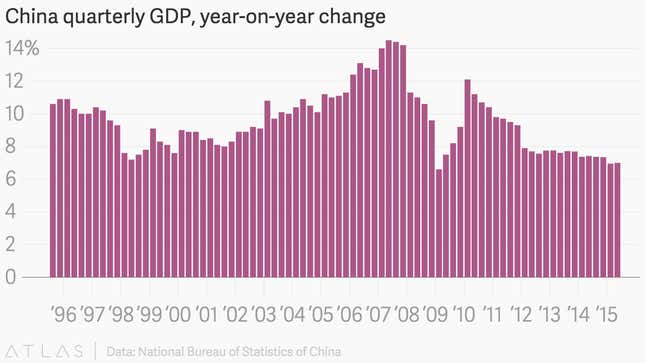

But it’s also slowing.

This slowdown matters. A lot. China is the world’s largest consumer of—in no particular order—copper, steel, iron ore, automobiles, aluminum, mobile phones, nickel, rice, tobacco, meat, Swiss watches, television, rubber, potash, energy, robots, beer, machine tools, red wine, flavored milk, rare earths, wheat, coal, as well as plenty of other raw materials and products.

And because of China’s seemingly endless demand for such sundries, companies—and entire countries—have built their business and economic strategies around catering to the People’s Republic.

That means China’s problems are the world’s problems.

Brazil Beware

Look at Brazil. China is its largest trading partner, buying up tons of Brazilian iron ore and soy beans. Weak Chinese demand has hammered prices of such commodities. For example, prices for iron ore—the key ingredient for Chinese steel mills—are down more than 60% over the last two years.

Predictably that has meant Brazilian iron ore export revenues have fallen, too.

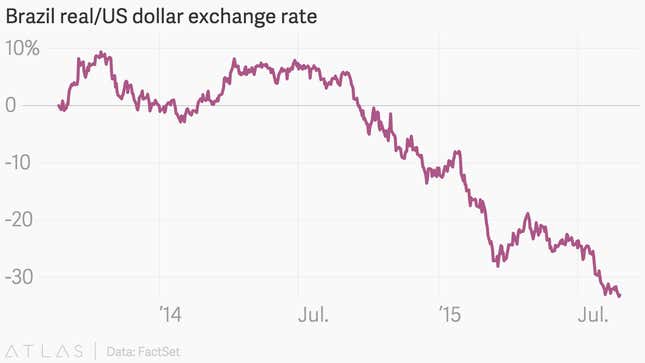

Here’s the thing about buying Brazilian commodities. To do it, you need Brazilian money. In general, rising exports push up the value of a currency. On the other hand, falling exports push a currency down. That’s what happened to the Brazilian real. It lurched lower by more than 30% against the US dollar over the last two years.

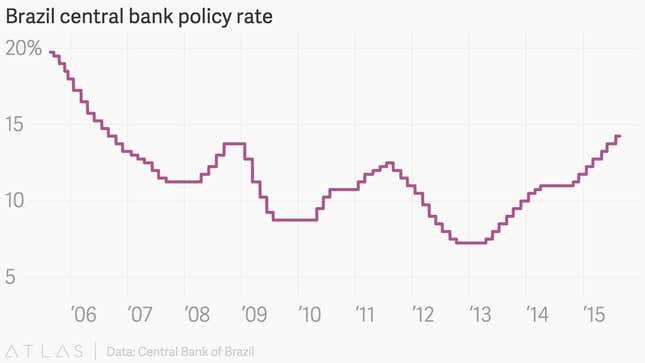

The feeble currency, in turn, has set off inflation in the country…

… which prompted the central bank to start raising interest rates…

… which has slowed down the economy. Brazil might have entered a recession in the second quarter.

Germany

China, of course, doesn’t just import raw materials; it also imports finished goods.

For instance, China imports a ton of the automobiles and machine tools that Germany specializes in making. And over the last decade, that’s been a huge boon to the German economy.

But there have been signs of cracks. BMW recently reported declining sales in China last quarter for the first time in a decade. And share prices for German auto giants Daimler, BMW, and Volkswagen have all moved sharply lower in the aftermath of China’s devaluation on Aug. 11. After being up as much as 40% earlier this year, these companies have lost all their gains.

Japan

China is what the Japanese like to call a “double bummer.”

Like pretty much every other economy on earth, Japan exports a ton of stuff to China, essentially as much as it does to the US, its top trading partner. So weak Chinese demand is a drag on its economy.

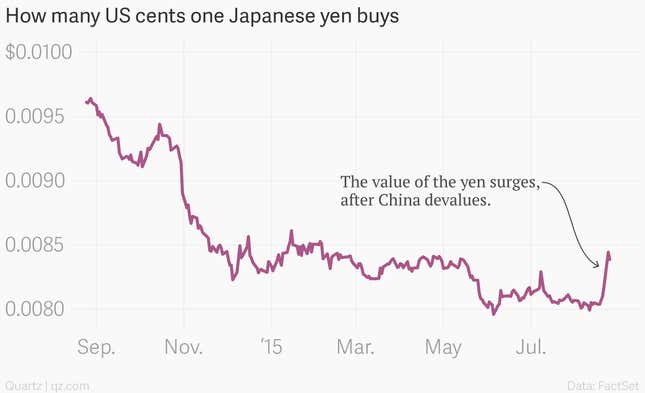

On top of that, the China-driven global market panic—set off by the devaluation—had driven Japanese investors back into the safety of the yen, pushing up the value of the currency.

That’s a problem, as Japan has spent the better part of the last few years trying to weaken the yen as a way to help its exporters. A strong yen is the last thing the country needs as its efforts to revitalize economic growth show little sign of catching fire.

US

The US economy is not built around supply exports to China. So, in that sense, the country enjoys a bit more insulation from China than many others.

But the US does import a lot of stuff from China, and one of the most important imports—at least lately—has been deflation.

Because of slack conditions in the Chinese industrial sector, producer prices—prices of goods as they leave the factory gate—have been tumbling.

That, along with the devaluation of the Chinese currency, should put further downward pressure on US import prices.

Ostensibly that’s a good thing for consumers.

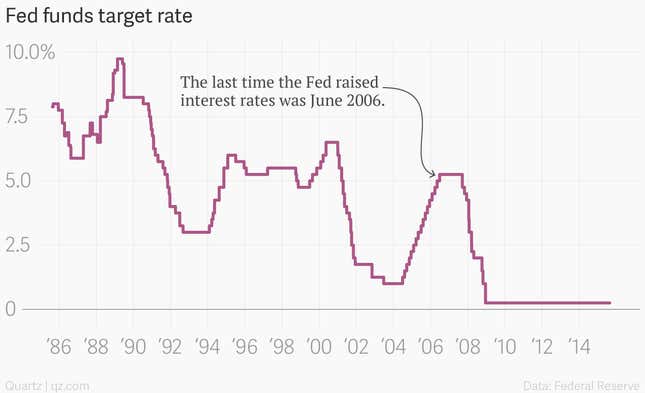

On the other hand, that deflationary pressure will make it even more difficult for the Federal Reserve to achieve its goal of getting inflation up to a level where it feels like it can raise interest rates. Inflation remains abnormally low, largely due to low oil prices. But the Chinese situation won’t help matters either.

Markets are now much less sure that the Fed will finally start raising interest rates for the first time in roughly nine years in September.

And there’s more

What about New Zealand? China’s voracious appetite for dairy products means the People’s Republic now rivals Australia as a top trading partner.

The UK? Its commodity-heavy stock market has been hit especially hard among European indexes.

Not to mention all the other commodity exporters such as Russia (oil), South Africa (metals), and Australia (iron, coal) that also find themselves in a similar spot.

The possibly-ending story

As sophisticated as they may seem, financial markets run on narratives. And the clear takeaway from recent events is that markets—that is, investors—have lost their faith in the reassuring notion that Chinese growth will always be there to give a helpful upward nudge to the global economy. And that changes everything.