Paleoanthropologists have it hard. Their entire careers can be spent working on a femur or a mandible in the hopes that the bones may reveal some secret about our ancestors.

But Lee Berger of the University of Witwatersand in South Africa has had amazing luck. In 2008, in Malapa cave in South Africa, he discovered two full skeletons of a new species of ancient human. ”We have no other collection of fossil skeletons, until the Neanderthals just over 100,000 years ago, that are so articulated, so complete,” another paleoanthropologist remarked on Berger’s findings then.

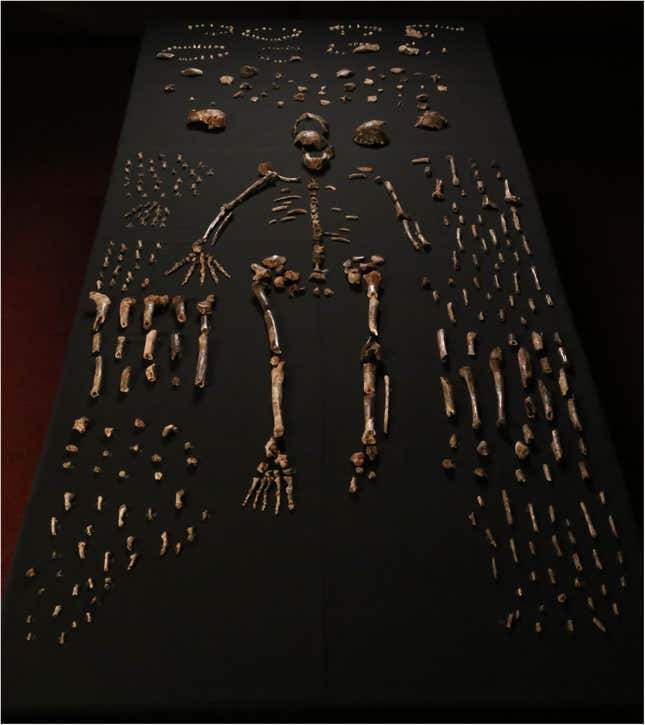

And, now, Berger has broken his own record. In the Rising Star cave, also in South Africa, he has unearthed more than 1,500 bones belonging to 15 individuals of another new species of ancient human, which include a range of male and female adults, elderly, and infants. “To find one complete skeleton of a new hominin would be hitting the paleoanthropological jackpot,” remarked science writer Ed Yong in The Atlantic. “To find 15, and perhaps more, is like nuking the jackpot from orbit.”

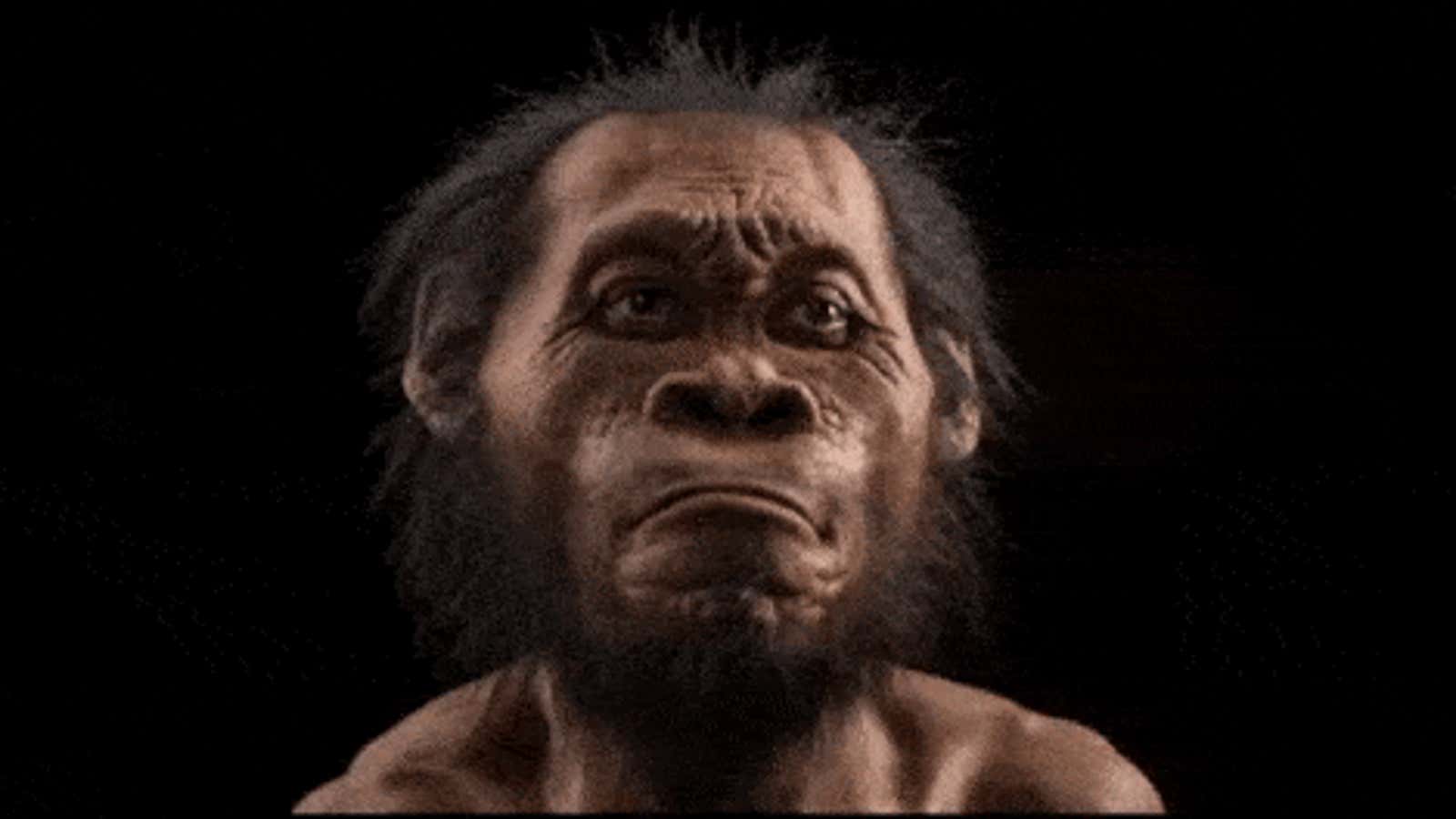

The species has been named Homo naledi—where naledi means “star” in a local language. The upright ancient human would have stood at about five feet tall in adulthood. The feet seem to have been built for long-distance running. The arms are ape-like, and hands human-like. The skull is tiny—only a third the volume of a Homo sapien’s brain.

The other intriguing find is that, apart from those 15 skeletons, the hard-to-reach cave was bare. “We found nothing else, and the only time you ever find just one thing is when humans deliberately do it,” Berger told The Atlantic.

The speculation is that the species may have “buried” their dead, which is something that isn’t seen in most ancient human species. Of course, speculation is all that is because we know don’t know any more about H. naledi.

Berger and his colleagues haven’t even dated the bones yet. The species could be millions of years old or only thousands of years old, and that would mean very different things for where it fits in the human tree.

There is also a chance that the skeletons don’t represent a new species. Some past claims have not held up under more detailed scrutiny. Still, Berger’s find will go down in history as a remarkable discovery—and one that made a lot of paleoanthropologists very jealous.