US Energy Secretary Steven Chu confirmed that he will leave his position a few weeks into President Barack Obama’s second term. Chu is something of a nerd hero: A Nobel-prize-winning physicist for his work on how lasers affect cooling atoms, he was a professor at Stanford University and then the director of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. At Berkeley, Chu led the lab to focus on biofuels and solar energy, while warning against the negative effects of climate change.

When Chu was appointed in the heady days after Obama’s inauguration, he became the aspirational vessel into which the nation poured its green energy hopes: Who could be better qualified to develop US energy policy in the new century? He also symbolized the Obama administration’s belief in science—not something that might need emphasizing in other developed countries, but in America, a pointed contrast to the increasingly anti-scientific mindset of the Republican party.

Alas, it was not to be. The bulk of policy decisions are made at the White House, and after a major climate-change bill failed in the spring of 2010, Washington’s priorities changed from climate change—which before the 2008 election was a bipartisan affair—to a partisan battle over the economy.

Thus Chu’s common-sense idea to paint more roofs white was derided. His efforts to use green energy stimulus money to boost important research was succesful, by the standards of Congressional legislation, but conservatives made the failure of one funded company, Solyndra, a political bludgeon for the administration. Ultimately, his legacy is mixed: He helped make cleantech a growing economic sector, but also leaves behind an energy department without a clear strategy.

Whatever his qualities as a visionary and manager, Chu was a great symbol of what the Obama administration wanted to do for energy. As his colleague in the cabinet, the also-outgoing Secretary of Transportation, Ray LaHood, told him early in their tenure, “Look, you’re window dressing. You’re more of a prop. But it’s part of what we have to do.”

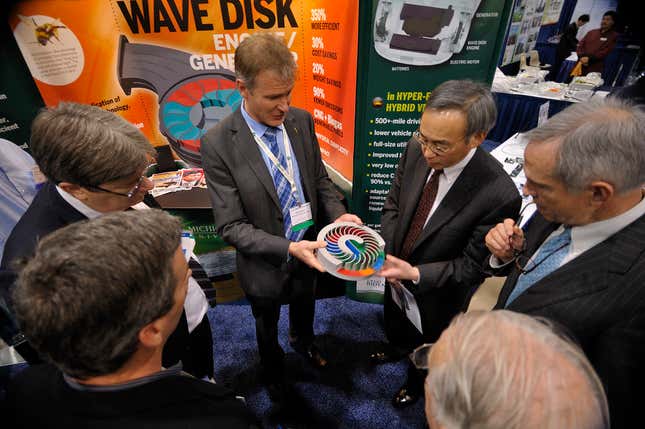

In short, a key part of his job was to go around visiting researchers and energy entrepreneurs, be seen looking at their work, and thereby invest it with his personal authority and that of his office. So here are some pictures of Steve Chu looking at things.

And if you’re wondering who might replace Chu, here’s one speculative list, ranging from the wildly unlikely (Elon Musk) to the much more feasible (Susan Tierney). An insightful wrap up of Chu’s legacy at our sister publication, National Journal, suggests that former North Dakota Senator Byron Dorgan and former Colorado Governor Bill Ritter are front-runners for the post—a belated acknowledgment that, next time, perhaps a politician will do better than a scientist in the job.