You may think that you’ve seen this film before. If all you see is the poster, trailer or Google promo for Yann Arthus-Bertrand’s stunning latest opus Human, it’s easy to dismiss the production as yet another beautifully photographed but unstartling documentary—the kind you might play in the background as you do some chores, or later fall asleep to. But within a few minutes into this film, you’ll realize that the subject of the film is actually you—and that you cannot look away.

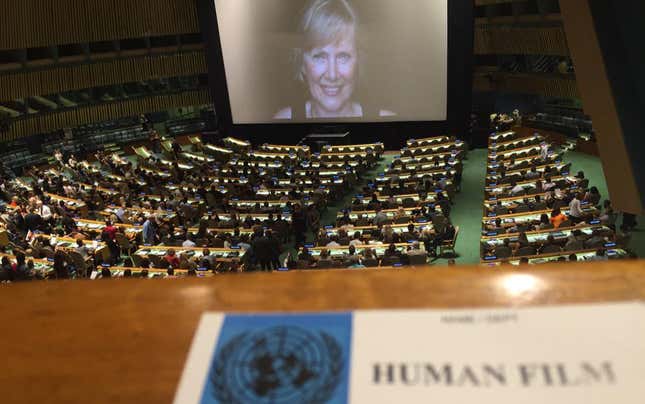

With UN Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon in attendance, Human premiered on Saturday (Sept. 12) at the refurbished United Nations General Assembly Hall in New York City.

The setting alone should be a clue to this film’s worldwide resonance. Stirring, sad, and funny, a string of first-person interviews filmed in over 60 countries delivered an expansive meditation on universal questions: Why are our differences so great? What is the meaning of life? What is love?

“This is movie is not about answers,” Arthus-Bertrand later told Quartz. “It’s really about the questions.”

No special effects needed

Human must be among the most ambitious testimonial projects in film history. Over the course of three years, the celebrated French director and photographer has assembled a rich montage of over 2,000 stories. Vignettes about love, forgiveness, violence, remembrance, longing, regret, anger, and joy, are loosely pieced together in untitled thematic sections.

Each subject is presented on a plain black background with no details about their identity or locale. The camera never moves. There’s no musical score to amp up the emotional torque of the interview. The power of each person’s story is spectacular enough.

A Syrian woman glows when she speaks about love—and leaving her husband.

Uruguay’s former president José Mujica, looks ruffled as he reflects on his life.

An Afghan refugee delivers a sobering testimony on the pain of displacement.

At times, an interview teeters into polemic, like when the occasional subject chooses to address the audience directly, imploring world leaders for action or begging for aid. But the film’s greatest strength is its restraint. Just as a photographer works with light and shadow, Arthus-Bertrand is a master at balancing gravitas with levity; intimacy with expanse.

The “human effect”

The film is long, but perhaps necessarily so. At interludes, slow motion shots of landscapes and crowds are set to the score by Arthus-Bertrand’s long-time collaborator, Armand Amar. These extended segments showcase the director’s longtime métier—aerial photography.

Shot high above, the big-screen perspective is so stunning that it induces that perspective-shifting “overview effect” that astronauts say they experience when looking at the Earth from outer space.

From its premise, the scope of Human is monumental. The film was fully financed by the Bettencourt Schueller Foundation, which backs entrepreneurs in science and culture, as well as humanitarian projects. Produced in collaboration with Arthus-Bertrand’s ecology-focused foundation GoodPlanet, Human appears conceived as a sort of public service; according to the film’s website, its distribution is designed to be made under “the freest conditions to the widest possible audience.”

Arthus-Bertrand, who has been knighted and medaled many times over in France but is less well-known in America, says he hopes that the film will be seen by as many people as possible.

This masterful work, with extended segments available for free via YouTube—should not be missed. To see Human is humanizing.