More than six years after the end of the Great Recession, America’s middle class is still waiting for its recovery.

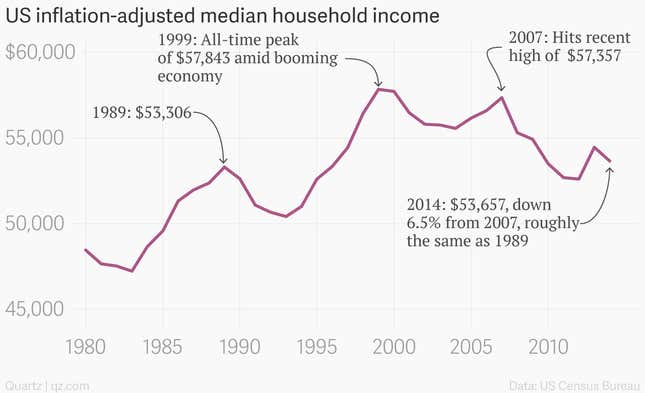

Inflation-adjusted US median household incomes suffered another flat year in 2014. In newly-released data, the Census Bureau pegged real US median household incomes at $53,657, statistically flat from the previous year. (The median income is the exact midpoint of US income distribution—half of households in the nation have incomes that are higher, and half have incomes that are lower.)

Over the long term, the picture is pretty clear. Effectively, inflation-adjusted US median household incomes are still roughly where they were in 1989, when they hit $53,306. That means the American middle class hasn’t made durable progress for 25 years. And median household incomes are still more than 6.5% below the peak back in 2007, when they were $57,357.

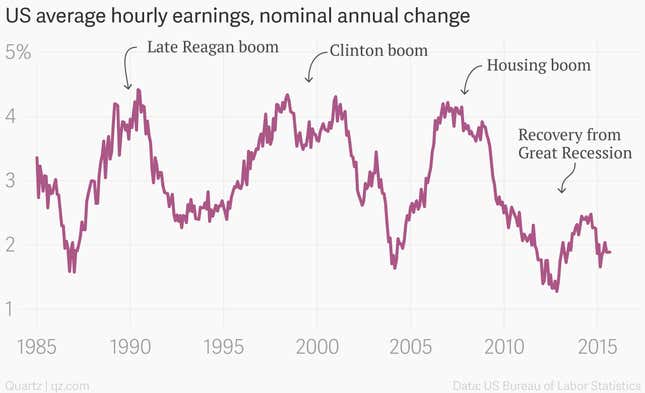

It should come as little surprise that household incomes have stagnated in recent years. After all, nominal wage gains this time around have been downright puny by the standards of other recent economic recoveries.

The stubborn refusal of household incomes to rise remains a frustrating hangover from the Great Recession, the worst US economic downturn since the Great Depression. But the data shows American standards of living began falling long before Lehman Brothers went bust seven years ago this week. Aside from a brief increase during the worst of the housing boom that preceded the Great Recession, US household incomes have been on a downward trend for around 15 years.

Why?

As per usual, economists have a number of different explanations. Some, such as MIT’s David Autor, point to increased polarization of the US labor market, where so-called “middle-skill” jobs—such as sales, office and administrative and factory workers—are increasingly being replaced by automated technologies. Such jobs represented roughly 60% of US employment back in 1979. By 2007 these jobs only amounted to 49%. By 2012, they were a mere 46%, Autor wrote in a 2012 paper. Unsurprisingly, wage growth for these types of jobs has been much slower than it has been for professional, technical and managerial jobs.

Increasingly, researchers are also looking at trade as a culprit. Trade—while beneficial to consumers buying cheaper goods—has hammered blue-collar wages in the US. An influential paper published last year found that workers who were forced to switch from manufacturing to lower-skill jobs between 1983 and 2002 saw real wage declines of anywhere from 12 to 17 percentage points. Some six million US manufacturing jobs were lost over that period. An update to that paper, which pulls results forward to 2008 finds an additional two million lost manufacturing jobs.

In other words, the benefits of trade are unevenly spread. Consumers with safe jobs win by getting access to cheaper products. Workers who compete with lower-cost foreign factory workers lose their jobs at the plant and have to take more fragile, lower-paid positions.

But there’s one class of American workers who seem blissfully unaware of the deleterious aspects of trade: politicians. Democrats and Republicans have found precious little to agree on in recent years. But free trade is one of the things they seem to be able to get together on.

And there’s probably a good reason for that: They usually don’t spend their time with the blue collar crowd. (Reports have put the percentage of millionaires in Congress at more than 50%.)