Shortly after the world celebrated Nigeria’s success in going a year without a single diagnosed case of polio on July 24, disturbing new outbreaks crippled children in Ukraine and Mali. Two cases in Ukraine turned out to be ”vaccine-derived,” feeding local fears of the vaccine, and providing fodder to anti-vaxxers worldwide.

On Sept. 2, The Washington Post published an article titled: “Outbreak of rare, mutated poliovirus that originated from vaccine in Ukraine leaves two children paralyzed.” This, although true, framed the issue in a way that led to misunderstanding; the article has since been (mis)quoted by people who believe that immunization is actually responsible of a resurgence of polio.

There is no cure for polio, a highly contagious disease that once left hundreds of thousands paralyzed around the world. However, since the 1950s, there is a vaccine for it. Two, in fact. And even despite the possibility of “vaccine-derived”-infections, universal immunization remains the only way to ensure that no more children are paralyzed in the future.

Quartz spoke with Dr. Jay Wenger, a former epidemiologist with the US Center for Disease Control, who now leads the Gates Foundation’s polio eradication program. In the interest of clearing any doubt that might cause parents to leave their children unvaccinated and vulnerable, feel free to share the resulting explainer with the anti-vaxxers in your life.

How does the polio vaccine work?

Poliovirus is found in the wild in three different strands: type 1, 2, and 3. The type 2 wild poliovirus has been successfully eliminated through vaccination campaigns, while both type 1 and 3 are found in the wild. Both of them are highly infectious and cause paralysis.

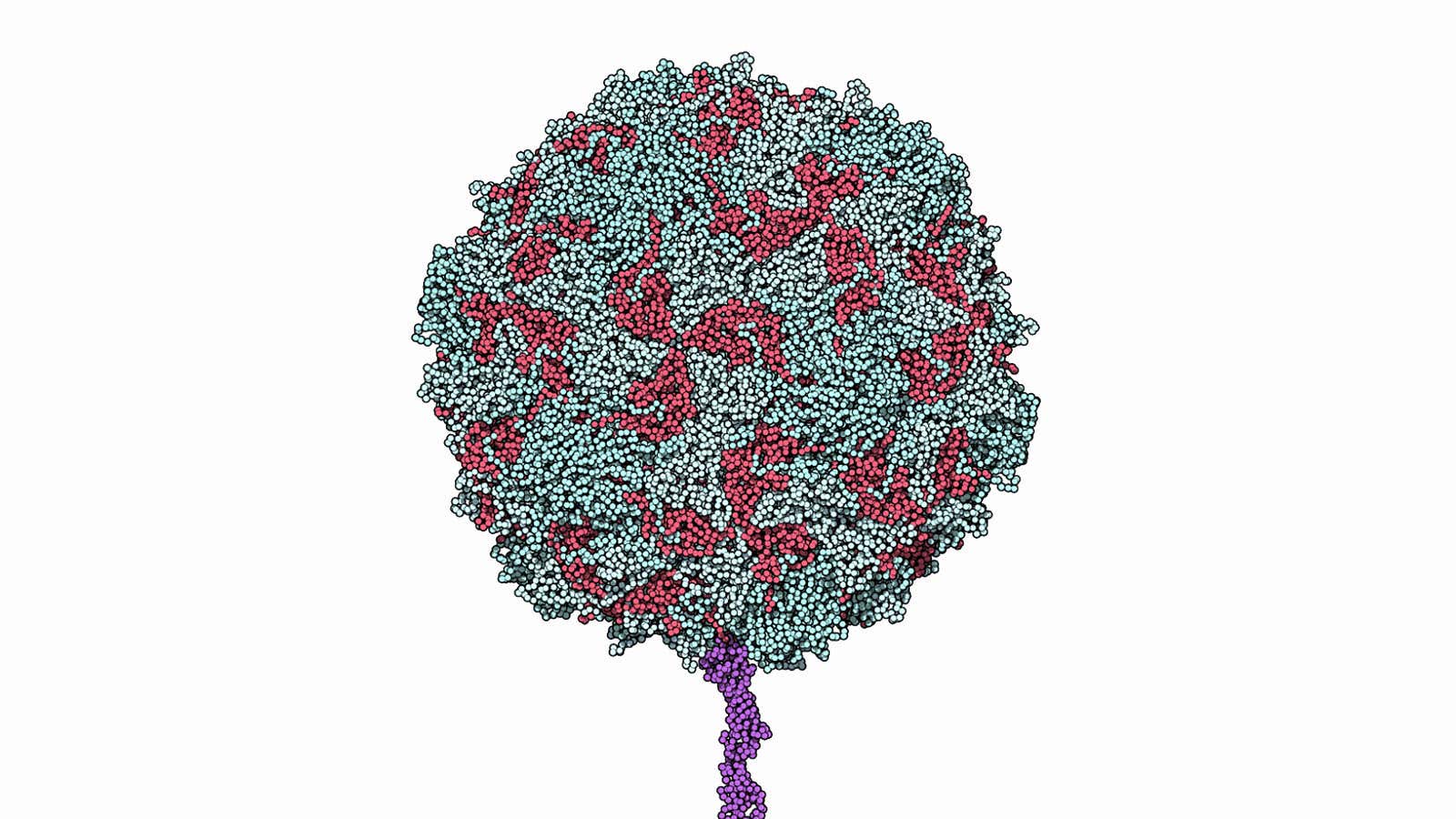

Inactivated Polio Vaccine (IPV): Developed by Jonas Salk, it has been in use since 1955; this vaccine consists of a dose of killed virus. Administered in three to four doses, it requires injections. Its cost would be of several dollars a dose, however it is available at $1 a dose in many countries.

Oral Polio Vaccine (OPV): The OPV was developed by Albert Sabin and has been in use since 1960. It consists of a weakened (attenuated) version of the polio virus, administered orally in three to four doses, through drops. It costs $0.12 to $0.15 and since it doesn’t require injections, untrained personnel can deliver it easily and safely.

This vaccine is the most widely used at the moment, and not only for simplicity and cost: the OPV has the advantage of immunizing the intestine, which is where the virus reproduces. Since the polio virus can’t reproduce outside the human body, areas where the OPV vaccination drives are widespread end up eliminating wild poliovirus. Thanks to the OPV immunization, the wild poliovirus has been cornered to the region of Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Currently, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that countries continue OPV immunization campaigns until their entire population is declared polio-free (that is, three years after the last case), then switch to the IPV or a combination of the two. This is because, in very rare cases, the use of OPV can lead to vaccine-derived outbreaks.

How do vaccine-derived outbreaks happen?

When kids are vaccinated with OPV, the weakened virus stays in their stomach for about two weeks, while the body develops antibodies for it. The virus is excreted through feces, and it can end up contaminating water bodies, especially in areas with poor sanitation, and get in contact with other children, particularly in crowded areas.

When immunization levels are high, that doesn’t matter, because the chances of the virus entering in contact with an unvaccinated kid are extremely low. When, on the other hand, the vaccination levels haven’t been high, the virus might be contracted by an unvaccinated child.

This doesn’t mean that the child will develop polio. However, if the virus spreads from an unvaccinated child to another, or to family members, and the transmission chain continues for long periods (usually at least 12 months, though it can take less), there is a very small chance that the attenuated virus could end up mutating back into an active form.

This is technically known as circulating vaccine-derived polio. It only happens in areas where the vaccination levels are very low to begin with.

How do we handle vaccine-derived outbreaks?

The good news is, vaccine-derived polio outbreaks are much easier to control than wild polio outbreaks, and represent a less serious threat. The immediate response should be to increase vaccination coverage, not scare people away from the vaccine.

In the longer term, once wild polio virus disappears from every corner of the world, OPV immunization can be replaced by IPV, which minimizes the risk of mutations.

Are there any other scenarios of polio infection?

Well, yes. In 0.0001% cases, a child given a first dose of OPV vaccine can develop paralysis. The risk is minimal, however, compared to the risk of not vaccinating children and allowing this highly contagious disease to spread unchecked.

Thanks to global vaccination efforts, since 2000, according to the WHO, over 10 billion doses of OPV have been administered to about 3 billion children. We are now close to a polio-free world. Once that goal is accomplished, there will be no more live virus (in the wild or weakened in the vaccine) and every possible chance of contracting polio will be eliminated.

The only way to get there is the path we’ve been following so far: vaccinate, vaccinate, vaccinate.