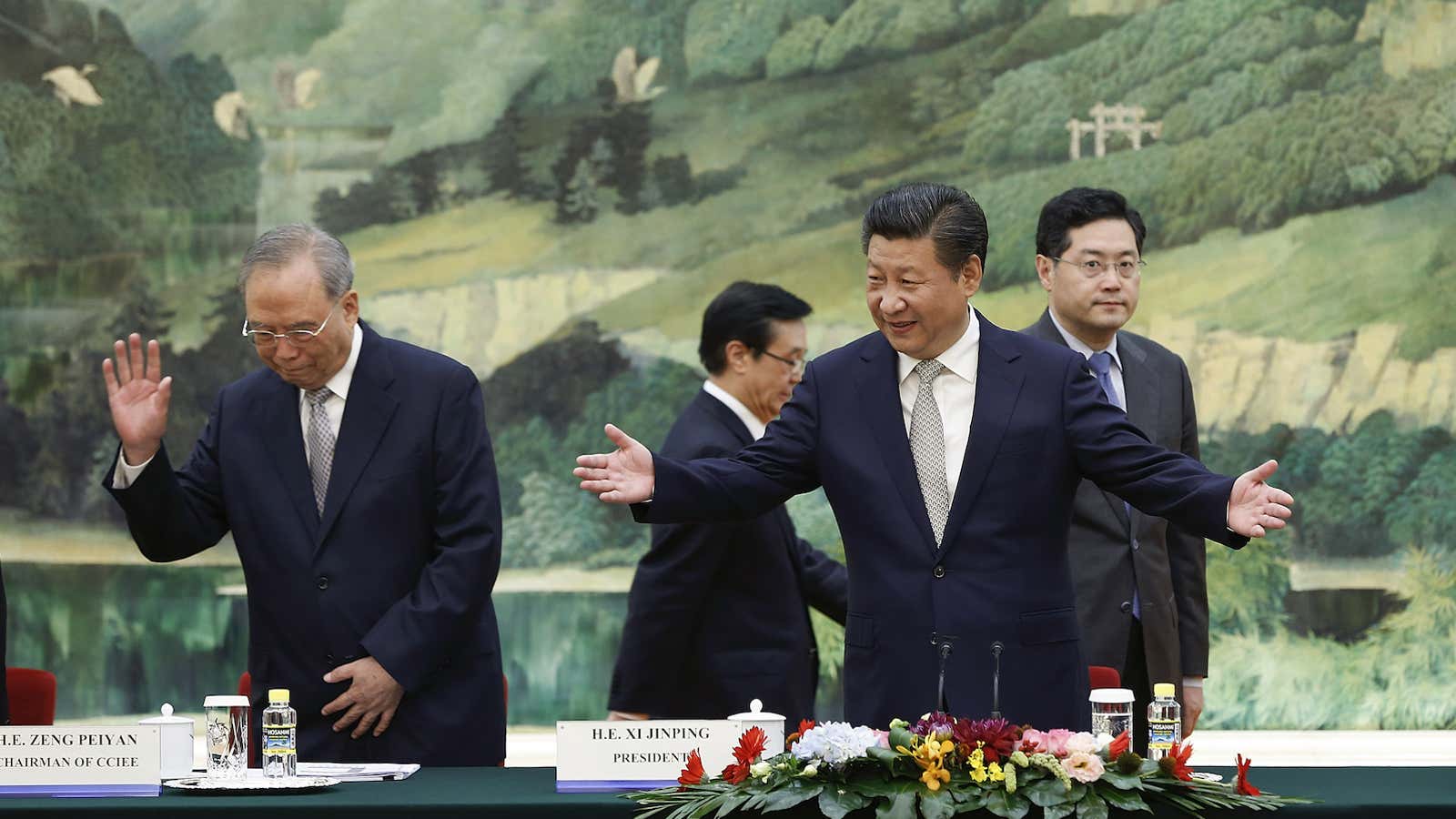

Much of the high-gloss diplomacy surrounding Chinese president Xi Jinping’s state visit to Washington next week will be familiar to observers. There will be the photo ops, a state dinner, a wooden press conference featuring Xi and president Obama. As Xi struggles with a slowing economy and embarrassing disasters such as the Tianjin chemical explosion, Chinese leaders are especially eager for the summit to be a success—and, as is the case in China—using all means necessary to ensure that there is no criticism.

Xi Jinping’s brutality is less well appreciated than that of other leaders like Russia’s Vladimir Putin. But in his two years in power, Xi has reintroduced hardline rhetoric and retrograde tactics: stressing ideological purity for Communist Party members, reviving the practice of public confessions and sentencing rallies, and disappearing critics. His government detains peaceful activists for months at a time with virtually no due process rights while blithely proclaiming adherence to the rule of law. China increasingly hunts people seeking refuge from Beijing’s persecution overseas and, of course, remains the only government in the world to imprison a Nobel Peace Prize winner.

Some of the usual features of a high-profile state visit can’t help but remind one of the bare-knuckle tactics China employs at home. Chinese state media outlets will run advertising supplements in US media just as rosy and scrubbed as the propaganda featured domestically. China might use the visit to request the return of citizens wanted on corruption charges, causing one to ponder whether they can get humane treatment, a fair trial, or indeed any trial in China. Lafayette Park—just opposite the White House—will be closed on the days of the visit, perhaps for security reasons, perhaps for public relations reasons and perhaps at the request of China, which locks down critics and routinely sweeps public gathering places of any possible protest for major events.

But Chinese authorities are also preparing for the visit in ways that aren’t so visible. Some Chinese students will no doubt be compelled to cheer Xi’s arrival (though some may also do so willingly). Activists and their family members in China and in the US have been told by Chinese authorities not to participate in protests during the visit, threatening unspecified consequences. Radio Free Asia correspondent Shohret Hoshur, a US citizen who reports from Washington on developments, including human rights abuses, in his home province of Xinjiang, knows this problem all too well: his brothers are being prosecuted in Xinjiang in clear retaliation for his work.

Two other events reflect growing sophistication by Beijing in selling the Chinese government’s version of reality to a well-informed and powerful audience. On Sep. 17, Washington’s high temple of policy discussions, independent bookstore Politics and Prose, hosted Chinese Ambassador to the US Cui Tiankai and a “very senior Chinese government official not yet specified” for a discussion of President Xi’s book on governing China.* To be clear, there’s nothing wrong with Politics and Prose hosting such an event, but the fact that Chinese government officials sought this venue reflects a far more nuanced understanding of how to influence policy-savvy Washingtonians—who should bear in mind no such event could happen in China.

Similarly, some of the most powerful technology companies in the US, including those who have been vigorous opponents of American surveillance practices, are dispatching their CEOs to a Seattle meeting with Lu Wei, China’s senior Internet czar, who who oversees the “Great Firewall” of censorship inside China. Unless they are prepared to make clear statements in defense of privacy rights and the freedom of expression in China, these CEOs will in effect lend their prestige to Beijing’s ever more powerful internet censorship and surveillance.

Everyone involved in the visit—from President Obama to the National Park Service, from newspaper marketing departments to progressive bookstores to the CEOs of Apple and Google—can help combat Beijing’s impulse to censor and intimidate critics.

Now is the time to encourage and enable peaceful protest and debate, to invite cheerleaders and critics alike of the Chinese government into the Oval Office and salons. With the clock winding down on his term, President Obama has little to lose in taking a tough stance on human rights with President Xi—and in so doing setting an example for the next president of the United States. To do any less would not only betray those in China struggling to achieve the human rights so many observers of the visit enjoy every day, but to encourage Beijing to step up complicity in repression both at home and abroad.

*Correction: An earlier version of this article stated that the Politics and Prose event would be held on Sep. 23, when in fact it was held on Sep. 17. The sentence has been corrected.