Among the many nasty side-effects of the European debt crisis, bigotry’s return to pleasant conversation may be the least-commented upon, and the nastiest.

Granted, few actually say Germans are power-hungry, scatologically-obsessed skinflints. And it’s only usually hinted broadly that Spaniards are hot-blooded, undisciplined spendthrifts; and Greeks shiftless tax-dodgers. Those people, you know?

Likewise, Ireland’s debt-fueled housing boom and banking bust—which eventually dragged the entire country under—is often dressed in ethnic livery. The Irish went on a bender and they’re dealing with the hangover. They’re guilty, have confessed their sins and willing to years of painful austerity budgets as penance.

That last bit, the submission to painful remedies demanded by foreign authorities, has earned Ireland something of a starring role in the ongoing European morality play: that of “the good debtor.” (“Greece has a role model and the role model is Ireland,” Jean-Claude Trichet, former chief of the European Central Bank, famously said back in March 2010.)

But this overlooks a few uncomfortable details. Ireland’s homeowners are the European and perhaps the world champions in not repaying mortgages. The country’s national debt has increased fourfold in about as many years. Its banking system is being kept afloat by borrowing from Europe. And while a change in the law may soon force the banks to start cleaning up their balance sheets, nobody is quite sure how bad a mess they will find there when they do.

Welcome to Ireland, where the hangover is in fact just beginning.

The Rising

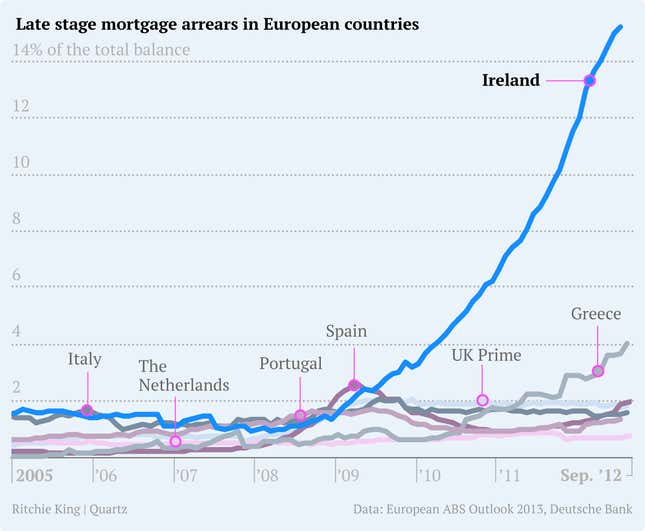

In the last few years, a staggering number of Irish homeowners have simply stopped making mortgage payments. The Irish central bank says that at the end of December 2012, 11.9% of Ireland’s mortgages were late by more than 90 days, up from September’s 11.5%.

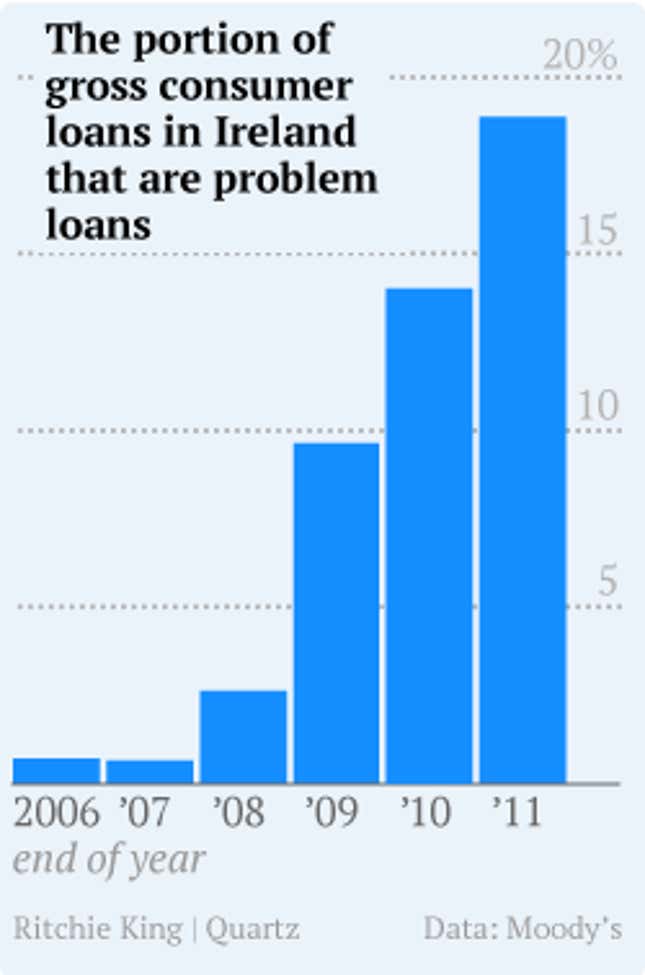

And the truth is probably even worse. The chart above, which was produced by Deutsche Bank using Moody’s data, pegs the percentage of Irish mortgages that are three months late somewhere closer to 16% in September. S&P analysts argue that 25% of Ireland’s home loans are in some kind of trouble, either behind on payments, or in foreclosure, or in forbearance, which is when the bank just isn’t collecting payments. (We’ll get to why later.)

Why? To be sure, things are tough in Ireland. The recession has driven unemployment from less than 5% at the end of 2007 to more than 14%. Incomes have crumbled.

But Greece is in an even worse economic crunch. Unemployment is at 27%. The economy has shrunk by 25% since the end of 2007. Newly impoverished people are turning to firewood because they can’t afford heating oil. And even so, the amount of Greek mortgages in late-stage arrears was only 5.1% in November, according to Fitch Ratings.

What’s going on here?

Safe at home

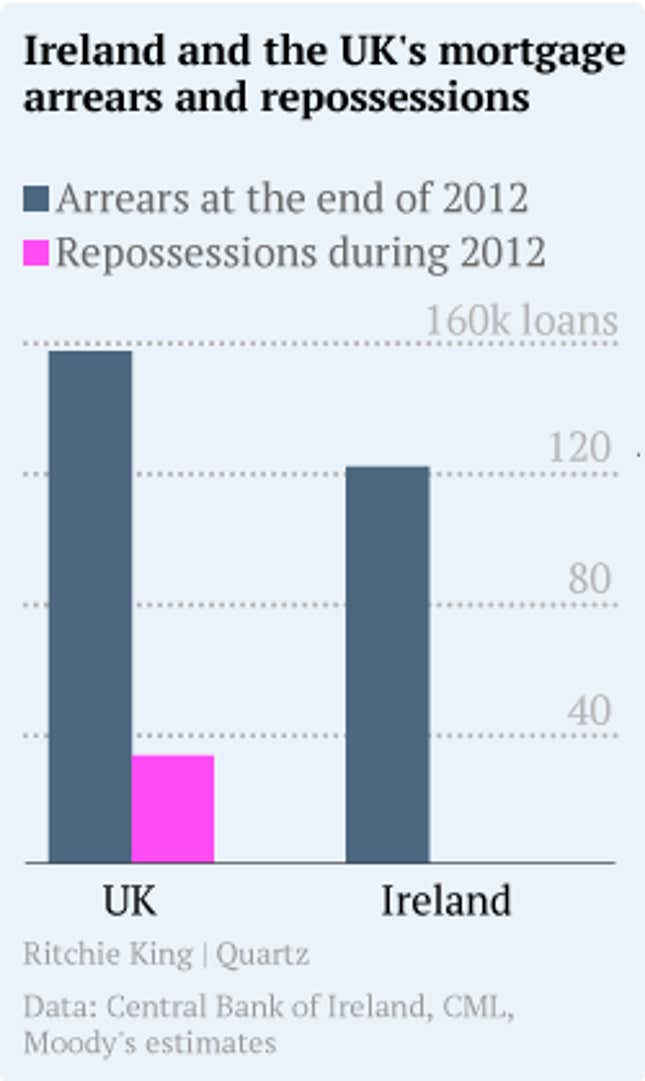

The simple answer is that Ireland is one of the hardest places in the world to drive a family from its home. Though thousands aren’t paying, repossessions of Irish homes remain ”negligible relative to the level of arrears,” according to a recent report by Moody’s analysts.

The most recent update on repossessions from the Irish central bank shows that during the entire fourth quarter of 2012 only 38 houses were repossessed by court order. At a pace like that, it would take more than 620 years to get through the backlog of nearly 95,000 mortgage accounts that are at least 90 days behind on payments.

The chart to the right is a look at the levels of problematic loans—that is, loans in arrears—in Ireland and neighboring Britain. In Ireland, repossessions are effectively non-existent.

In fact, Moody’s analysts note that the number of Irish delinquent on their mortgages shot higher in 2012, just as political discussions centered on the possibility of a large-scale debt forgiveness plan. (It never materialized.) Moody’s suggested that the increase was driven—at least in part—by some who are gaming the system. “The current dearth of repossessions and the recently proposed personal insolvency legislation is starting to result in higher defaults due to moral hazard,” the analysts wrote.

That’s financial-speak for “people think they can get away without paying their mortgage because they know they’re not going to lose their house.” Gregory Connor, a professor of finance at the National University of Ireland in Maynooth, estimates that about 35% of those who have fallen into arrears on their mortgages have done so “strategically.” That is, they can afford to pay, but just aren’t.

Birthplace of the boycott

There are any number of explanations for the dearth of Irish foreclosure. For one thing, Irish courts ruled in July 2011 that Ireland’s recently revamped foreclosure law contains a massive loophole. Long story short, the judge found that the law allows lenders to foreclose only on mortgage loans made after Dec. 1, 2009, when the new law went into effect. After the judgement, arrears shot higher.

The legislature could fix the the problem by passing a new law. But it hasn’t (although one is expected soon). And that’s likely because any Irish politician introducing such a bill would be brave indeed, given long-standing antipathy towards foreclosure and evictions among the Irish public.

After all, modern Irish patriotism first coalesced as a revolt against unfair evictions during the so-called land wars of the late 1800s. The period gave Ireland some of its earliest and most enduring political heroes—Charles Stuart Parnell, Michael Davitt—and villains, such as Charles Boycott, an unpopular, English-born magistrate and collector of rents from Irish tenant farmers. He gave his name, or rather he had it given for him, to the method of organized, non-violent shunning of which he was the subject until he was ultimately driven from the island.

Ancient history? Perhaps. But the notion of the sanctity of the family home still carries considerable weight in Ireland. In fact, the inviolability of a citizen’s dwelling is laid out starkly in article 40, sub-paragraph 5 (pdf, p. 158) of the constitution. So present is Ireland’s unpleasant history with eviction that Irish prime minister Enda Kenny felt compelled to give it a nod when he introduced a new personal insolvency bill last year. “There is probably no time, since the Land War, when the Irish people have felt so stressed, so anxious about their home and their family’s future security,” Kenny said. Given such historical and political backdrops, it shouldn’t be a surprise that Ireland’s legal and regulatory system is, as Moody’s put it in a euphemistic moment, “borrower friendly.”

You really owe it to yourself

But historical roots or not, Ireland’s arrears mess is a real problem. It means somebody lent money and is at increasing risk of not getting it back. So who might not get paid back if Irish homeowners continue on their current path of flaky repayment? Here, things get a little bit circular.

You see, during the boom years Irish banks made the bulk of house loans that are now going bad. But the Irish government—that is, the taxpayers—now owns a large share of those banks, thanks to the roughly €64 billion ($82 billion, or 40% of GDP) it has poured into them since 2008, according to S&P analysts. So in a sense, Irish homeowners owe this money to Irish taxpayers, who are one and the same.

But wait, there’s more.

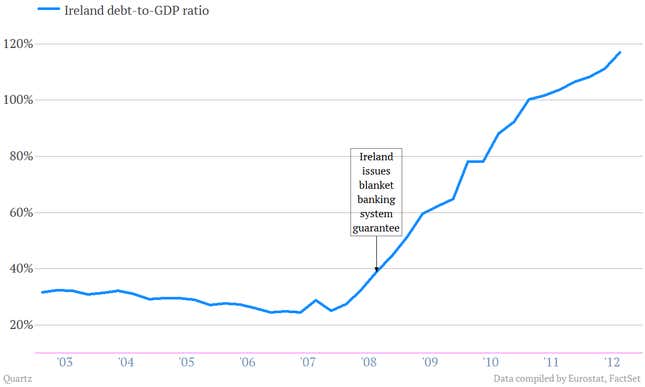

You see, Ireland itself didn’t just happen to have €64 billion lying around. It had to borrow it. Here’s what that did to Ireland’s debt-to-GDP ratio, which has surged since Ireland issued a blanket guarantee on bank deposits and debt in 2008:

High Irish debt levels spooked the markets, as investors lost faith Ireland would ever be able to manage under the burden. Ireland ultimately had to itself be bailed out by a €67.5 billion line of credit from the “troika” (the ECB, the IMF, and the EU) on Nov. 28, 2010. And in a sense, that means that some of the risk of Ireland’s derelict homeowners is being born by its European neighbors.

Bad banks

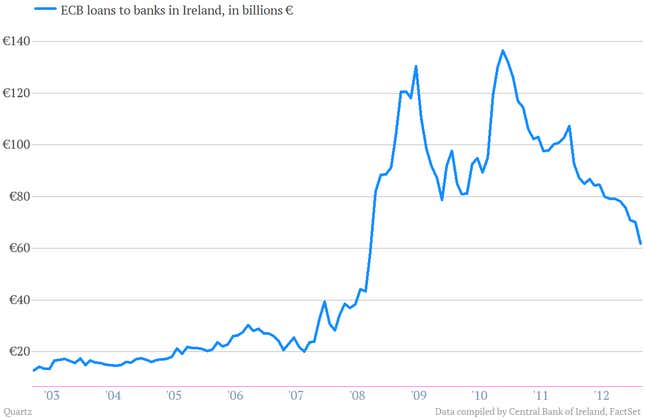

Nor did Ireland’s bailout mean its financial system was magically returned to the good graces of the markets. Its partially nationalized financial institutions still depend largely on borrowing from central banks to keep the lights on. The banks post some of their assets as collateral and get cash in exchange. Here is a chart of ECB lending to Irish banks, and you can see it surging as Ireland’s financial crisis worsened. It has fallen quite a bit over the last couple of years. But there were still €61.88 billion in ECB loans out to banks in Ireland at the end of February.

The Europeans have noticed

Ireland’s European lenders—the EU, the IMF and the ECB—know that the surge of bad mortgages is exposing them to increasing amounts of risk. And they don’t like it. In fact, in their latest report card on Ireland’s bailout program, they laid out steps the Irish government had to take to update the loophole in the 2009 foreclosure law, the one blamed for holding up foreclosures and repossessions. Those changes to the law are to be made “so as to remove unintended constraints on banks to realize the value of loan collateral.” In other words, the troika is telling Ireland to make it easier for banks to repossess and sell properties. Irish legislators are expected to pass a revamped law removing the loophole this summer.

So what’s the real risk here?

Nobody really knows.

Despite the fact that the Irish government yanked a ton of toxic assets out of Irish banks and put them into a “bad bank” known as the National Asset Management Agency (NAMA), and despite the fact that the Irish government has stuffed about €64 billion into the bank’s cash cushion, “the Irish banking system has not yet fully stabilized,” wrote Moody’s analysts in a January report. Short version: Irish banks own a ton of bad mortgage assets. (See the chart to the right.) But these are just the bad loans that we know of. Some think the true position of Irish banks may be even worse.

Worse?

Yeah, worse.

Some suspect it’s not just legal haziness keeping foreclosures low. Irish banks may also dragging their feet on restructuring or foreclosing. That’s because if they dealt with those problem loans by foreclosing or restructuring them it would, through the magic of accounting, transform hazy “problem” loans into real losses. In fact, there’s a well-documented history of banks procrastinating on recognizing bad loans in the aftermath of financial crises. Such widespread “evergreening” of bad loans was an insidious side effect of Japan’s financial collapse in the early 1990s.

And even if Irish banks do start dealing en masse with problem loans, it’s unclear how it could play out. On the one hand, it could mean more people in Ireland start to pay their mortgages, for fear of losing their homes. But a large wave of bank foreclosures could also “throw up evidence of under-reserving by banks as they start to close out some nonperforming mortgages,” according to a January report from Standard & Poor’s banking analysts.

In other words, it could reveal banks to be in worse financial shape than everyone thought. By extension, Irish taxpayers, the Irish government and its European rescuers would have to admit they face more risk than they knew. That would be a major embarrassment for both the Irish government, as well as its euro-zone sponsors, which have built up Ireland’s reputation as a debtor nation doing everything right.

The bottom line

But the growing pile of defaulting home loans holds other risks for Ireland. For one, it’s choking off the flow of capital to the economy.

Let’s remember why we even bother putting up with banks. They’re supposed to be good at doling out capital efficiently. They take the unused savings of society and channel it toward productive uses—at least in theory. But if banks coming out of a financial crisis start practicing widespread forbearance and evergreening of loans, they become less and less efficient at their job, because so much of their capital is tied up in bad loans instead of getting put to good use.

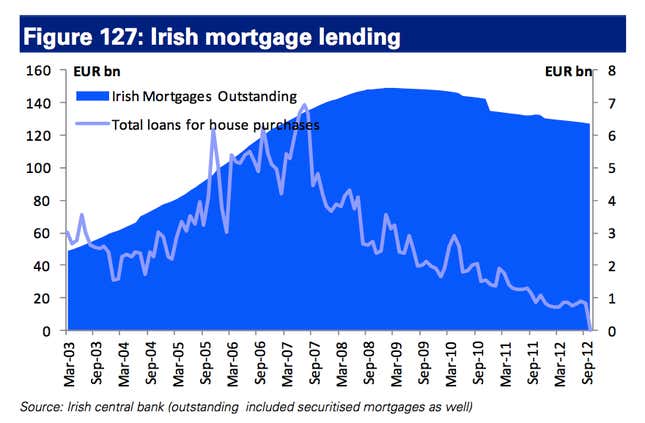

That’s part of what’s happening in Ireland right now. You can see, mortgage lending has pretty much collapsed.

Now, lending would logically fall after a financial crisis triggered by too much debt. But it will have to stop falling before the domestic economy starts growing.

That’s why Ireland must overcome its anti-eviction tendencies and clear the backlog of bad loans. And it’s not just the homeowners that will feel the pain through necessary foreclosures and repossessions. Banks must fess up to their losses and restructure bad debts.

It won’t be pretty or easy. But for the Irish government—so often dominated by the European powers that bailed the country out—it’s one of the few areas where it can still act. As for the European officials who have built Ireland’s painful austerity push into the “model” response for troubled European countries? They’re going to have to admit even supposedly virtuous Ireland is having serious difficulties making austerity work.