Gabriel Zucman is on a mission.

The 28-year-old French economist, currently at the University of California, Berkeley, has built his career remarkably quickly, and in the process has made a place for himself among the most influential economists working today.

Zucman decided, in part, to pursue a career as an economist after his experience working as an analyst for a French bank during the peak of the 2008 financial crisis. He remembers the shock of Sept. 15, 2008, the day US investment bank Lehman Brothers declared bankruptcy, the market chaos that followed, and the inability of both he—and more experienced colleagues—to understand the crisis as it caught fire.

To get a better grasp on what was going on, Zucman began digging into data from the Bank for International Settlements, the Basel, Switzerland-based entity that serves as a sort of “central bank for central banks.” As he sifted through the numbers, he was struck by something: Trillions and trillions of dollars in loans and deposits pouring into the tiny Cayman Islands, a well-known tax haven.

“So I had heard of this. And I knew that, in some sense, it existed,” said Zucman, during a sitdown with Quartz in Washington, D.C. earlier this month. “But [when] you see it in the data, it’s like, ‘This is so weird. Nobody is talking about this.'”

Increasingly, people are now talking about the importance of tax havens like the Caymans. In part, that’s due to Zucman.

After encouragement from his PhD. thesis advisor at the Paris School of Economics, Thomas Piketty, Zucman undertook an effort to assemble the sort of long-term data sets that have become a tool-in-trade for the explanatory economics Piketty and Emmanuel Saez have pushed to the fore in recent years. Such data-driven analysis was at the heart of Piketty’s surprise 2014 best-seller Capital in the 21st Century, which sought to describe how the distribution of wealth and income have shifted, leaving the developed world with the most unequal distribution of the fruits of the economy since the gilded-era that preceded the first World War.

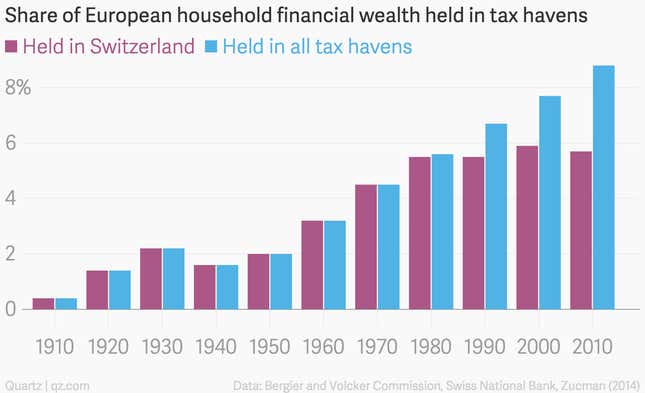

Stitching together data sets that chronicle roughly a century of offshore banking, Zucman shows how wealth in tax havens has grown to account for roughly 8% of total global household financial wealth, or roughly $7.6 trillion in 2014. About one-third of that is held in Swiss accounts. (Because Zucman’s numbers focus on assets such as stocks and bonds, and not real estate, he argues that, if anything, his estimates understate the share of all offshore wealth.)

Armed with those figures, he makes the case that tax avoidance and evasion are at the core of the issues such as inequality and financial stability. Here’s our chat, edited for clarity and concision.

Quartz: The heart of your book essentially tries to count up what we know about global financial liabilities—obligations such debt, stocks, mutual funds—and global financial assets, where we should find an equal number of bonds, stocks, and mutual funds as investments. You find that they don’t match up.

Zucman: Yes, there is a big mismatch between the financial assets that you can identify at the global level and the financial liabilities. But this gap has been known for quite a long time. In particular, IMF statisticians knew about that as far back as the 1970s. What was lacking was an understanding of what this means, where this comes from, and the reason.

So they identified the gap, but they didn’t have an explanation for it.

Exactly, they didn’t have an explanation. I mean, there were a number of potential explanations and nobody was really able to say this or that was causing the gap. I think I was able to make little bit of progress here in particular.

The point is that a large fraction of the gap—not all of it—but a large fraction of the gap actually comes from the fact that we don’t record the assets that individuals own through offshore bank accounts in, you know, the Cayman Islands, Switzerland, Hong Kong, Singapore, and so on.

So the title of the book is “The Hidden Wealth of Nations,” which is a not-too-subtle reference to Adam Smith. Even in the title you’re making the case that hidden wealth should be considered as a core part of economics. Why does it matter that this money is in Swiss banking accounts rather than just somewhere else?

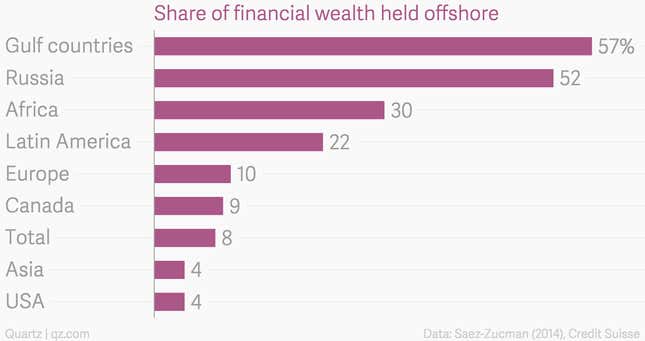

Well, this matters for a number of reasons. One is inequality; this is wealth that belongs to very rich people. If you are to have accurate measures of income and wealth inequality you need to take that into account. So, 8% of the world’s financial wealth, you could say, “Well, you know that’s not so much.” Except that it’s an average that masks a lot of heterogeneity.

For the US, maybe it’s as little as 4%. But for Europe as a whole it’s about 10%. And for some southern European countries, you know, think Greece, think Spain, Portugal, Italy this will be much more than 10%. For Latin America maybe 25%, Russia 50%. So if you want to study the distribution of wealth in those countries, it’s a first-order element to take into account.

The other reason is, it’s important to have accurate economic—in particular, macroeconomic—statistics if you want to monitor financial stability and if you want to conduct meaningful macro policies. Tax havens distort macro data in substantial ways.

We’ve been talking about household wealth and tax avoidance, but corporate avoidance is a bigger deal in terms of actual revenues, especially for the US. Correct?

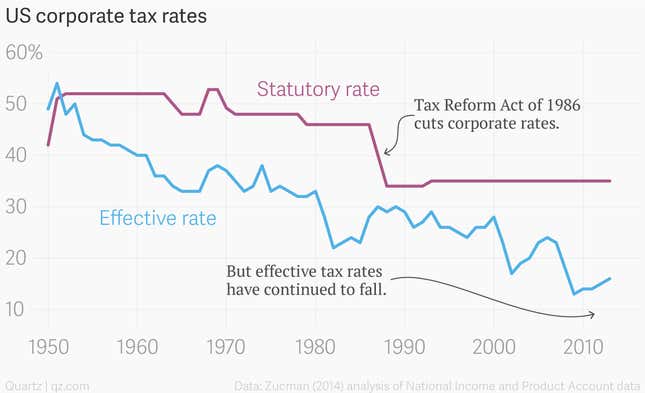

I think that’s the main reason why the US should be really concerned about tax havens. I mean, maybe there’s less US [household] wealth that’s hidden, compared to African wealth or Latin American wealth. I think that’s true. But if you look at the corporate income tax, the effective tax rate that used to be 30% in 1990s, has declined today to 20%—despite the fact that the statutory federal corporate tax rate has been stable at 35%.

Not all of this decline is due to tax avoidance in tax havens. But about two-thirds of this decline is due to artificial profit shifting. The revenue implications are big.

One of the things that I was really surprised at in the book: As tax rates came down a bit from the relatively high levels in the postwar era, US usage of offshore havens increased rather than decreased, which seems counterintuitive.

Social norms, in particular relative to taxation and tax progressivity, have changed a lot over time. For instance, if you were a CEO in the US in the ’60s or ’70s, or CFO, you were not going to try to minimize the corporate income tax as much as you could. People did not feel that this was their mission. Now, if you ask US CEOs or CFOs, they will tell you, “This our mission, if we can, to reduce the corporate income tax.'”

So the way that top executives think about their role, whether they have a fiduciary duty to society as a whole or to shareholders only, has changed enormously. And that explains how you have both a decline in top tax rates and and also a increase in tax avoidance and evasion.

You give a nice, concise summary on the development of tax havens and how they essentially originated in Switzerland after World War I, when tax rates went sharply higher in neighboring countries such as France in the aftermath of the war. You talk a lot about Switzerland, but it seems like your strongest writing is reserved for Luxembourg. Why does Luxembourg matter?

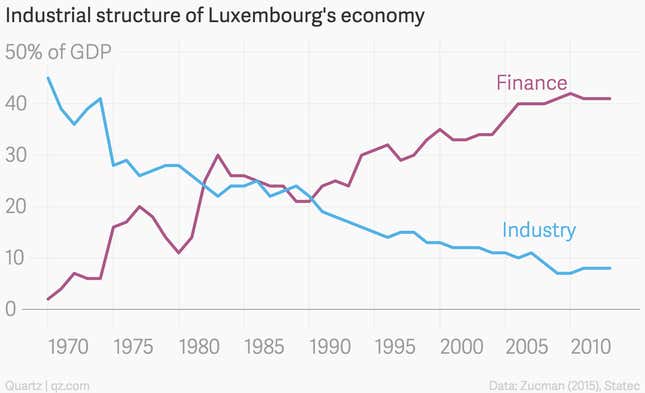

It’s hard to realize from the US and to understand what’s going on. But it’s very clear when you live in Europe because Luxembourg, like all other EU countries, has veto power on anything related to taxes and many other things. And they also have a clear interest. You know 40% of GDP in Luxembourg is finance, not all of which is related to tax evasion or avoidance, but a large fraction of which is. So they have a huge interest in preserving the status quo, preventing real reform, and it is just a big problem for the European construction.

It’s not very complicated to deal with the problem and solve these problems of tax evasion. Some people believe that nothing can be done. Cayman Islands? How can you make them change their policy? How do you influence Luxembourg?

Look the Cayman Islands are tiny islands. Luxembourg is 500,000 inhabitants. Europe is 500 million inhabitants. These are very small, in some cases, unpopulated countries. It’s very easy to lean on them and to make them cooperate and enforce taxes.

You tell the story in the book, which I had never heard before, of De Gaulle essentially cutting off Monaco in the 1960s to enforce the collection of taxes.

There is one road between France and Monaco, and this was shut down. And look what happened. Before that, French nationals who lived in Monaco paid zero income tax. Just because they lived on this side of the fence. On this side, you pay zero and on the other side you pay 50% or 60%. And after this, they became subject to the French tax law—which makes sense.