This item has been corrected.

On Sept. 25, for the second time in her young life, Pakistani activist and Nobel Prize laureate Malala Yousafzai addressed the United Nations assembly.

From the balcony of the UN General Assembly room, the 18-year-old told the world leaders seated before her to “look up, because the future generation is raising its voice.”

Flanked by 193 young people from around the world—one for each current seat in the United Nations—Malala demanded safety and education for all children. Then she introduced a few of her “sisters”—other young women who are working with the Malala Fund, a non-profit promoting education for girls inspired and led by the young Pakistani activist.

At a time when too many public female figures casually disavow feminism and gender politics, these fierce young women have traveled across the world to call for gender equality on a global scale. Quartz met each at the UN:

Kainat, 22, Pakistan

At 12, Kainat was gang-raped by four men, who then kidnapped her and kept her hostage for three days.

After she managed to escape and get back home—without shoes, or a dupatta to cover her head—she told her parents, who filed a complaint with the police. Kainat told Quartz that she and her family went on a 19 day hunger strike, refusing to eat until the police accepted her report.

That was just the beginning: Under threat, her family had to move from their original Dadu district in Pakistan to Karachi. Nevertheless, her refusal to drop charges against her attackers led to the kidnapping of two of her brothers, and one was murdered. Kainat, now 22, currently lives under police protection, and has only recently been able to resume her studies. Her rapists have yet to be convicted.

By challenging the system and refusing to hide, Kainat says she demands justice not only for herself but for other rape victims who do not report the crimes against them for fear of retribution.

Salam, 15, Syrian refugee in Lebanon

Fifteen-year-old old Salam and her family were smuggled from Syria into Lebanon two years ago, where they settled on the periphery of a refugee camp in the Bekaa Valley. Salam was only able to resume her studies July 2015, when she enrolled in a school financed by the Malala Fund.

“No one is paying attention to the lost Syrian generation,” said Salam, who has lost hope of going back to Syria anytime soon, to Quartz. She spends her free time convincing other refugee girls, including her own sister, to join the school, which is now attended by 100 girls, while 50 more are enrolling.

Aansoo, 21, Pakistan

Aansoo has had to overcome difficulties that would prevent even the most determined to continue studying, and now runs a primary school in her home village of Umerkot, Pakistan.

Born into an illiterate family in a Hindu minority, Aansoo lost her father in 10th grade. She suffers a walking disability, but nevertheless, completed her BA in the neighboring town of Kunri. In June 2014, before she even graduated, she had already decided to open a local school for young children. From 10 students with classes in a chicken pen to 336 students—200 boys and 136 girls—aged four to eight, Aansoo’s school has expanded quickly.

The 21-year-old is now helped by six other teachers, and counts disabled kids among her pupils. She teaches deaf and mute children using clay figurines she made, or using gestures. “You have to be innovative,” she told Quartz, explaining that her personal experience has committed her to providing everyone with equal opportunities.

Aansoo believes education is the only way to achieve a safer environment for girls. ‘There are a lot of rapes in the area,” she told Quartz, “and education is the only way for women—and men—to stop them.”

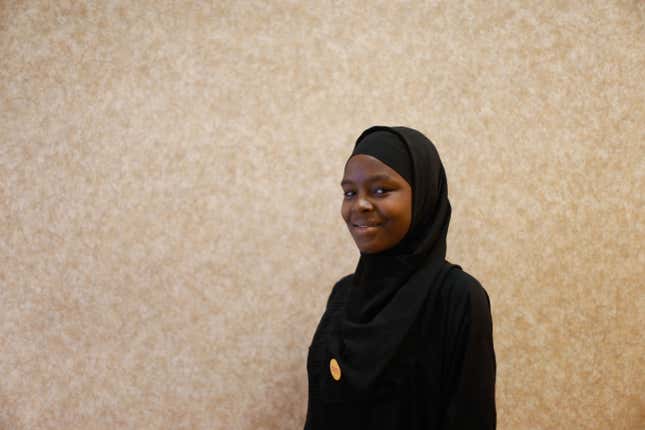

Amina, 19, Nigeria

Living in the north of Nigeria, where many girls become child brides, Amina is one of the very few young women attending secondary school. The 19-year-old campaigns for education around her community: after 276 schoolgirl were abducted in 2014 by terror group Boko Haram, she says, parents began withdrawing their children from school. She is vocal about the importance of education for girls, and also about changing disciplinary methods employed by some teachers in the region.

Children are routinely beaten or flogged if they are late, Amina told Quartz, and the physical punishment drives already low attendance down.”We need qualified teachers and equipment for people to enjoy learning,” she told Quartz. Amina also mentors more than a dozen girls aged 11 to 14 from her community, teaching them what she learns in school—from literacy and numeracy all the way to reproductive health.

Kainat, 17, Pakistan

Kainat, 17, was shot in the arm when the Taliban attacked the bus she was riding with Malala Yousafzai in October 2012.

After Malala became the focus of international attention, Kainat, too, became a target of the Taliban. She eventually moved to the UK with Shazia (a third girl who was injured in the attack). Kainat told Quartz that she is happy to study in a place where her family doesn’t worry for her safety when she wears a school uniform. She is planning to become a doctor and then return to Pakistan.

Before the accident, Kainat was aware of Malala’s efforts to promote education for girls, but, she told Quartz, “I didn’t expect that I could do this [being an advocate herself].” Now, promoting girls’ right to education has become her mission: She is still in touch with her community in Pakistan to help raise the number of local girls attending school, and participates in international events, including addressing the UN. In 2014, she accompanied Malala to Oslo, Norway, to accept the Nobel Peace Prize.

Shazia, 17, Pakistan

Shazia, too, was shot in the Taliban’s 2012 attack on a school bus in Pakistan, which she calls “the Malala accident.” After recovering from injuries in her shoulder and hand, Shazia left for the UK and attends boarding school with Kainat.

Like Kainat, she returns to Pakistan twice a year, despite the continuing danger of retribution for their activism. Shazia was in Oslo with Malala when she received the Nobel Peace Prize and is aware of her public role as the representative of a larger movement to promote education.

Despite threats to her safety, Shazia plans to return to Pakistan after her studies. “I want to do something not selfish,” she told Quartz. Acknowledging her luck in studying abroad, Shazia says it would be unfair if she didn’t give back to her original community. Malala, she says, taught her not to “wait for anyone to speak up for you.”

Correction: The women’s last names have been removed due to concerns about their safety.

![“Education is the only way for women—and men—to stop [rapes].”](https://i.kinja-img.com/image/upload/c_fill,h_900,q_60,w_1600/f98fc3fcf4831a6bcb19063bc7291a29.jpg)