The idea that Dell’s planned $24 billion leveraged buyout is basically about avoiding America’s pesky global tax regime isn’t as far-fetched as it may sound at first.

Like most American tech companies, Dell carries a lot of cash overseas. If it brings it home, it will pay US corporate income tax on it, generally at a 35% tax rate. This discourages Dell, like its competitors, from paying dividends to investors. With a leveraged buyout, the company’s private buyers borrow money in the United States and give that to shareholders, providing more value than if the company had paid them a dividend out of repatriated—and taxed—money.

Even better, the company can now deduct interest payments on all that new debt from its taxes. So if Dell’s new owners—led by current chairman and CEO Michael Dell—do bring that capital back from abroad in order to invest in reviving the company, they could offset the tax on repatriating their overseas cash with significant new tax deductions.

Such an approach would be a further buyout-enabled arbitrage on the US tax regime. Dell would effectively pay less tax to bring overseas cash home. And the private equity firms and banks will have made money financing the deal. Everyone wins, except Uncle Sam.

It’s not certain that Dell’s buyers planned the deal this way—we’ve reached out to the company for comment and will update with their reply—though there are hints that it plans to bring overseas cash back as part of the deal. And does it make sense to go through such convolutions for the sake of avoiding taxes? Two charts—and two wrinkles in tax law—make the case:

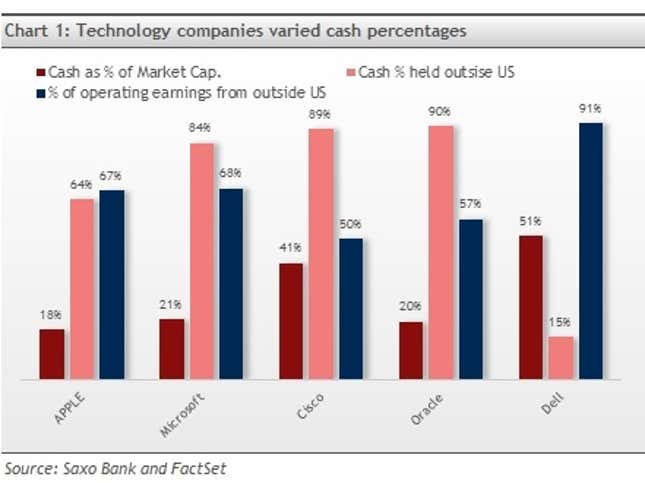

The first, above, compares the financials of Dell and several other tech firms. It’s from a research report on how the sector keeps cash overseas to avoid taxes. Though Dell keeps a relatively low percentage of cash abroad (and that number, from March, is likely understated) its cash reserves make up over half the company’s value, and most future earnings will come from overseas. Particularly relevant, as the analyst notes, is that Dell’s shareholder buyback program is an off-shoot of this incentive to avoid tapping into overseas cash for dividends. This buyout could be thought of as the reductio ad absurdum of that approach to bringing value back to shareholders.

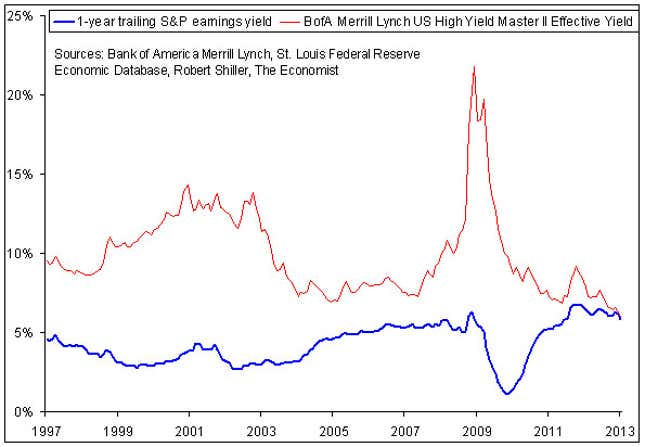

The second chart, showing the yield on junk bonds coming closer to that of the S&P 500, comes from The Economist. The magazine’s economics blog notes that the market conditions for buyouts are just right: Corporate debt is cheaper than equity. This makes it possible for private equity investors to perform an arbitrage, issuing debt to buy public companies and ride their growth—and the tax advantage America gives to debt financing—to profitability. But these conditions are somewhat unusual:

You might think that corporate debt should yield less than shares because debt has a higher place in the capital structure than common stock. However, equity owners have a claim on the bulk of any growth in profits over the lifetime of the company. This claim is generally worth more than enough to offset the junior status of equity holders in the event of bankruptcy, especially for firms that are not already on the brink of collapse. As a result, the earnings yield for a firm’s shares is usually lower than the yield on its bonds.

Besides the Federal Reserve’s efforts to keep interest rates down, another potential reason the situation is reversed today is that so many of the firms driving the S&P 500—we’re looking at you, Apple—keep much of the value of their companies overseas to avoid taxes, lowering the expected return on equity investments.

Absent tax reform that either forces companies to bring more of their profits back to the US or eliminates the duty entirely, American tech companies—and other multinationals that divert money abroad for operational or financing purposes—will face pressure from shareholders to deliver value in more roundabout ways. And if private equity investors can harness that incentive, the tax deductibility of interest, and an attractive spread between financing options, there may be more big buyouts in the offing.