Cambridge, England-based ARM Holdings just released its annual report, and two facts stand out: The first is that the company is on track for explosive growth. The second is that most of ARM’s future revenue, all of which comes from royalties, will almost certainly derive from licensing deals the company has already locked in.

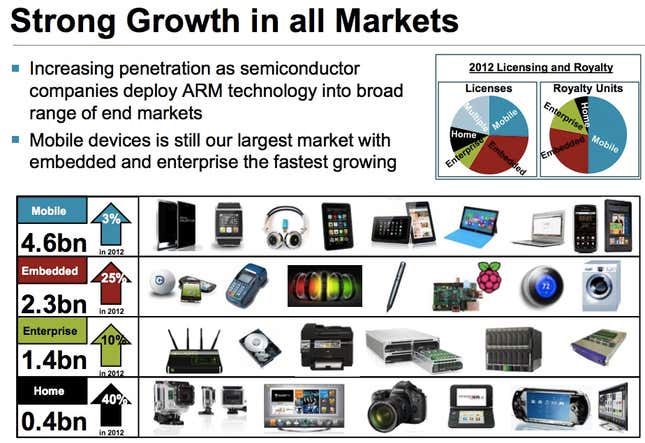

ARM does one thing exceptionally well: Design the innards of the microchips that appear in almost every smartphone or tablet you’ve ever laid hands on. Their licensees, who take ARM’s reference designs and modify them for their own needs, include Apple, Samsung, Qualcomm and countless other manufacturers of fast but power-sipping microchips. But it’s not just mobile devices—ARM chips also show up in the boxes that pipe content onto our TVs, the infrastructure that enables our internet connections, and even an increasing share of the servers in data centers with which we communicate every time we open a web browser or stream a movie.

It’s worth noting that ARM remains a shockingly small company, given its influence. Its value on the stock market is only $20 billion (ailing PC maker Dell just went private for $24 billion). Its fourth quarter revenue was up 19.2% from the same period last year, but was merely $164.2 million. Compared to giants like Samsung and Apple or even mid-sized technology companies like HP and Dell, ARM is small fry, indeed.

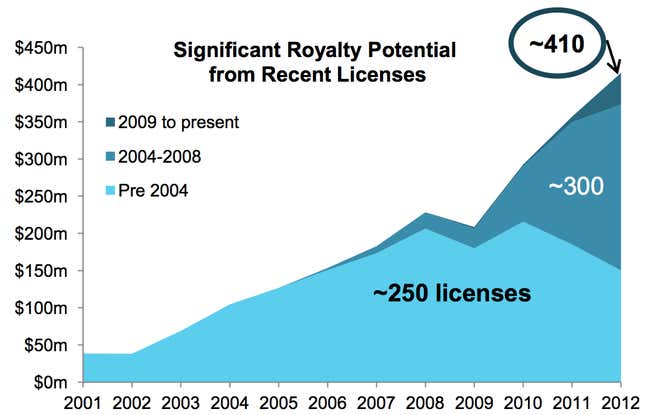

And yet more than 90% of its income came from licenses it signed with manufacturers before 2008, according to its annual report. Of its approximately 960 licensees (some, like Apple, the company does not publicly acknowledge) 410 signed with ARM since 2009. It’s not clear that those licensees will sell as many chips as the first 550. But if they did, ARM’s revenue could be expected to increase proportionally in the coming years.

Aside from global explosion of sales in smartphones and tablets, ARM’s projected growth comes from the sheer ubiquity of processors made by its licensees. As our world becomes ever more computerized, ARM is becoming a de facto standard. It’s not an exaggeration to say that ARM chips are in everything from your smartphone to your washing machine, and that future gadgets will in some sense be uniquely enabled by the combination of power, small size and low electricity use that is the trademark of ARM’s designs.

It is perhaps this commitment to staying specialized, and relatively small, that is the secret to the company’s success. Unlike Microsoft, which is now making its own hardware, ARM does not compete with its licensees. Its competition includes Intel, which is five times as large and a great deal more profitable. But unlike ARM, Intel has so far pretty much missed the mobile revolution, and it manufactures its own chips and has enormous investments in the “fabs” required to do so.

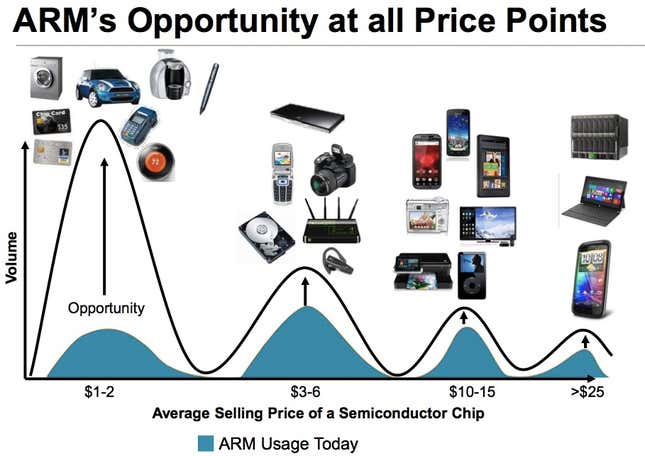

One reason ARM has pushed aside Intel in many applications is that while Intel is very good at creating some of the world’s fastest chips, it hasn’t been as good at creating lower-power chips for mobile devices. Another reason is that ARM’s licensees make very low margins on their chips compared to Intel, so their microprocessors sell like commodities, for as little as $1-$2 a chip.

While those margins might be low, the variety of places that ARM shows up means it will be in tens of billions of devices, from the microcontrollers that run a city’s wastewater infrastructure to the in-dash computers in cars.

On the other hand, some of ARM’s projections for its high end microchips strain believability. As mobile analyst Benedict Evans pointed out, if ARM is right about the size of its “opportunity” in this area, it would imply that by 2017, iPhone sales will triple. There are, of course, threats to ARM: Intel is getting much better at making the chips that go into smartphones, and has already started showing up in devices like Motorola’s well-reviewed Razr smartphone. And companies like MIPS, which has almost the same business model as ARM, do quite well selling the same kind of cheap-but-effective designs for chips for telecommunications infrastructure and other “embedded applications.” But it’s hard not to look at its latest annual report as anything other than the proud report card of a company that, perhaps unexpectedly, finds itself at the center of a sea change toward mobile devices and ubiquitous computing.