Bhim, a small town in Rajasthan, was witness to a poignant protest on Mahatma Gandhi’s birthday last year. Girls at the local government school chose to honour the father of the nation not by garlanding his photo, but instead practicing what he taught—satyagraha or civil disobedience. Hundreds of girls sat outside the school gate to make a basic demand—they need more teachers. At that time, their school with an enrollment of 700 girls had just three teachers. Since then, the number of teachers has gone up by only two.

The children’s struggle highlights the challenges that India, and many other countries, will face in meeting the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) adopted by the United Nations (UN) last week.

If the transition from the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) to the SDGs is to be anything more than a name-change, India has to grapple with a paradox. It must pursue gross domestic product (GDP) growth, and at the same time, redefine growth to equate it with actual well-being instead of the size of the economy in terms of money.

A combination of economic growth and aid programmes has so far resulted in dire poverty being reduced by half across the world. In India, the poverty headcount ratio, which was estimated at 47.8% in 1990, had been reduced to 21.9% by 2011-12, four years ahead of the MDG target (pdf).

However, India is still home to a quarter of the world’s undernourished population. Over a third of the world’s underweight children and nearly a third of the world’s food-insecure people live in India.

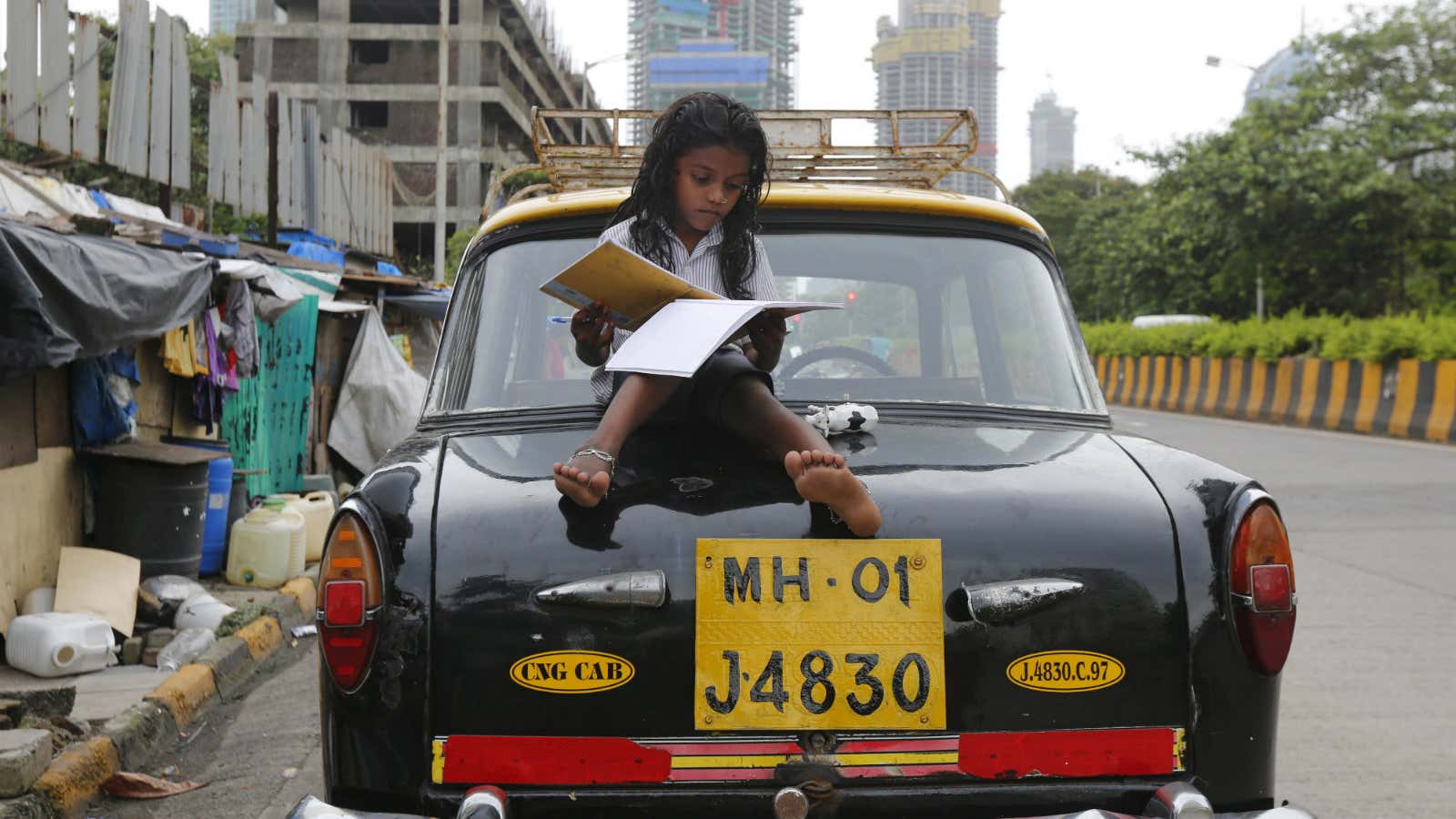

Outcomes in the sphere of education are equally grim. The completion of primary education by all children was one of the MDGs. The net enrollment rate in primary education, of children from age 6 to 10 years, has gone from 84.5% in 2005-06 (pdf) to just 88.08% in 2013-14. Even more significantly, the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER), an Indian civil society initiative, has shown year after year that even among children who are in school actual, learning rates are abysmally low.

In the case of child mortality, India has made substantial progress—reducing it from 125 deaths per 1000 live births in 1990 to 42 deaths per 1000 live births in 2015. Maternal mortality rate has declined from 437 per 1,00,000 live births in 1990 to 167 in 2011-13. These are substantial gains, even though India has missed its MDG target in both cases by a small margin.

While the MDGs were entirely focused on improvement of rather basic indicators of human well-being, the SDGs have a more multi-dimensional and ambitious framework. Apart from aiming to eliminate poverty and hunger, while also ensuring health and education for all, the SDGs commit all nations to crucial institutional goals—such as peace, justice and strong institutions, reduced inequalities, responsible consumption and production, climate action, decent work and economic growth.

All of the above will not be possible unless nations and the UN move towards redefining growth. Higher GDP remains the primary goal of economic policy across the world. The UN’s Human Development Report is taken seriously but remains a poor second in terms of importance.

Among governments, Bhutan with its gross national happiness measure remains an exception for instituting a holistic measure of achievement. Otherwise, it is the global civil society sector that has been more creative and inventive. The New Economics Foundation in the UK annually puts together the happy planet index, which tallies for each nation people’s experienced well-being, life expectancy and ecological footprint.

The Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI)-Atlantic, a Canadian NGO, produces an index that shows all depletion of natural resources, including fossil fuels, in the negative column. Social problems like ill-health, lack of education also show up as negatives—thus keeping the focus on actual well-being.

While GDP measures nothing more than the sum total of money that has changed hands, GPIs shift the emphasis from accumulation of monetary assets to regeneration of the natural resource base and creation of human well-being through better schooling, health care, sanitation, and cleaner air.

India is already consuming natural resources at 70% above its bio-capacity annually. Thus, a good deal of what currently shows as GDP growth is actually the equivalent of drawing on the principle and showing it as income.

In the absence of a structural shift in what is measured as income and what shows up as a loss in national accounts, any comprehensive attainment of the SDGs might be impossible—not just for India but for most countries.

Prime minister Narendra Modi’s speech at the UN on Sept. 25 indicated that India’s strategy for meeting the SDGs is a combination of economic growth and public welfare programmes. He specifically highlighted programmes for welfare of the girl child as a key element of this strategy.

However, as the protest by the school girls in Bhim show, the litmus test for this will be neither the number of operational schools nor children enrolled—both of which are neatly captured by GDP data. What matters is whether both the children and sufficient teachers showed up and effective learning actually happened—something ASER attempts to map.

The key challenges going forward are volume of money globally committed to fulfilling the SDGs and the equation of how markets will intersect with public spending. But nothing is more critical than replacing the supremacy of GDP with a more holistic measure of both economic dynamism and social-environmental well-being.

This post first appeared on Gateway House. We welcome your comments at [email protected].