When Jana co-founder Nathan Eagle needed to connect to a cell carrier in the developing world, he’d come to meetings with a duffel bag full of cash and say that he wanted to buy airtime. For carriers who were taking on more customers than ever, but struggling with declining revenue per user, it was an irresistible sales pitch. The result, two years later, is that Jana is now the largest payment platform in the world.

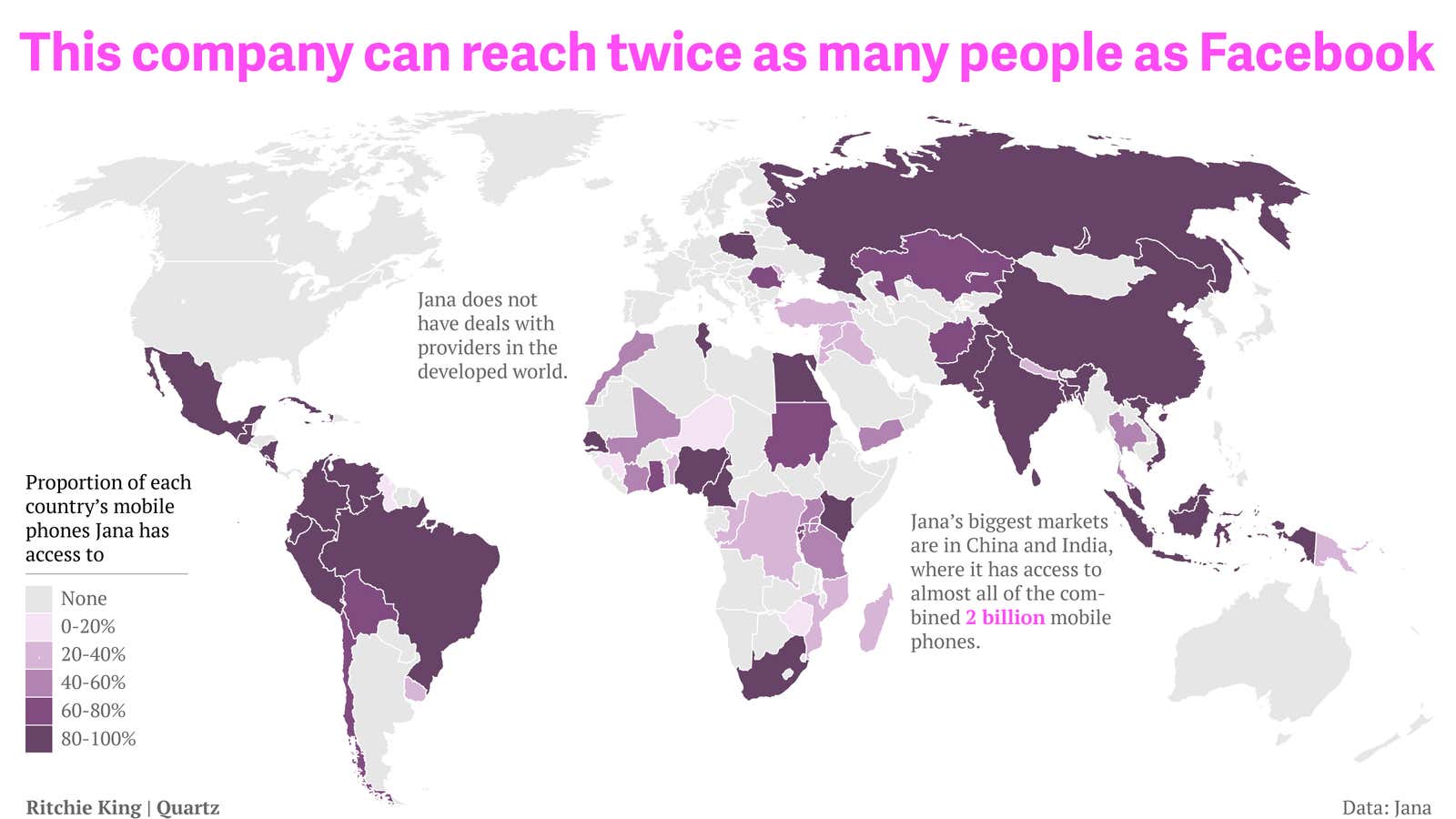

Eagle describes Jana as an “opt-in mobile network” that pays users to fill out consumer surveys and try products. The company has access to 100% of the users on 237 cell carriers in 101 countries throughout Asia, Africa and Latin America.

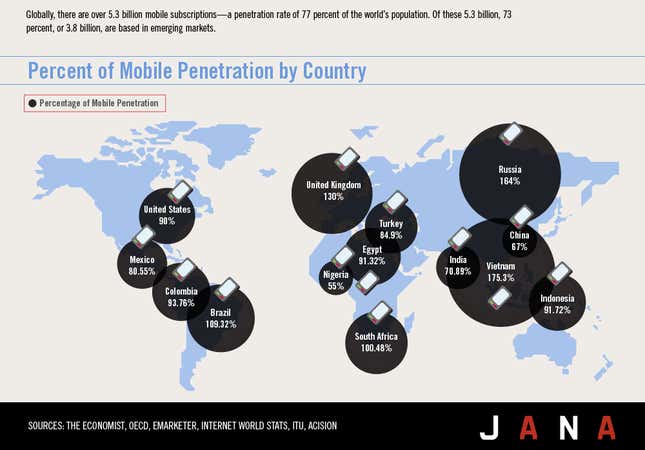

By 2004, there were more mobile subscribers in the developing world than in developed countries, and the gap has been widening ever since. In 2012, Jana estimates that of the 6.5 billion mobile subscriptions on Earth, 5 billion are in emerging markets. The World Bank estimates that 75% of the people on Earth have access to a mobile phone. According to the McKinsey Quarterly, three billion people are projected to move into the middle class in the next twenty-five years. Right now their mobile devices are in some respects the most direct way to reach them.

Eagle comes from an academic background—he has appointments at Harvard and MIT and once more than a year as a Fulbright professor in Kenya—and his roots lie in using technology for development and social good. Jana was born, in part, of Eagle’s success in setting up a network in rural villages in Kenya for nurses to text in status reports on supplies of hospital blood banks.

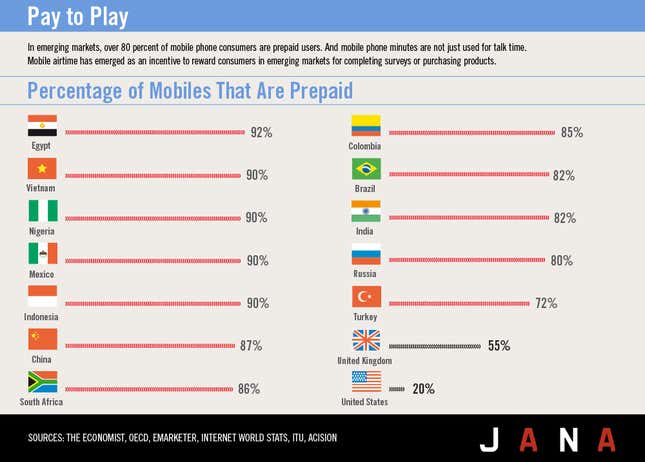

Jana’s network, which is connected directly to the computer systems used by mobile carriers around the world, doesn’t send actual money; instead, it gives mobile-phone credit. In emerging markets, where, according to Eagle, the average user spends 8%-12% of his or her income on prepaid mobile service, that’s almost as good as cash.

From his office in Boston, Eagle can credit money into the prepaid accounts of more than 2 billion handsets around the world, instantly. “We know the 850 million prepaid phone numbers in India,” says Eagle. “We can pick one at random, tap in ’50 rupees,’ and when I push enter, no matter where it is in India, whether it’s an old school Nokia or an iPhone, that rural subscriber is going to say “Hey I just got 50 rupees.”

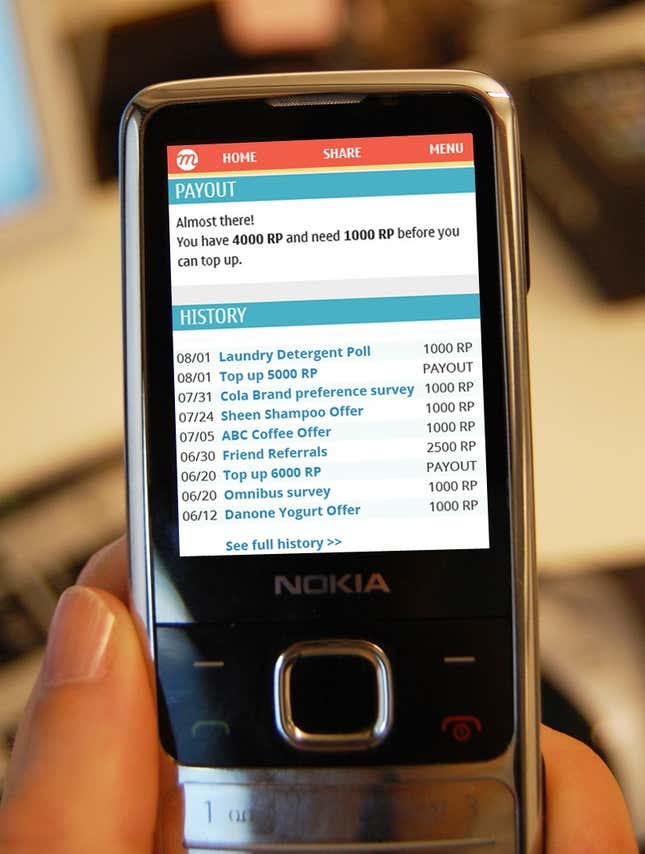

Jana mainly reaches users through a mobile-friendly website or—for the minority of its users with full browsers on their phone—a Facebook app. Users can choose from a list of tasks they can perform in exchange for credits: For example, Microsoft once asked Jana to have its users answer questions about an interface Microsoft was testing.

Often, Jana links its promotions to purchases in the physical world. ”In the Philippines, if you go out and buy a particular brand of candy bar, if you get three of your friends to also buy it, all of you get it for 50% off.” says Eagle. “We can validate the purchase because 7-Eleven is now printing Jana IDs on every receipt they have. At any of 713 7-Elevens, it’s on the receipt.” In another promotion, consumers in Indonesia who purchased two or more Danone yogurt products got 5,000 rupiahs ($0.52) worth of airtime directly on their phones.

Marketing to the millions

Of course, Jana is not the only firm enticing mobile-phone subscribers to answer marketing surveys and redeem coupons; it merely has the biggest reach. But reach is not the only thing that matters, says Donald Fitzmaurice of Brandtone, one of the few companies with ambitions as broad as those of Jana. Advertising is an extremely local phenomenon, tuned to regional tastes and trends, he notes. ”If you were to compare us with Jana,” says Fitzmaurice, “Jana claims access to everyone in the world. What we do is we combine total access with the ability to work closely with brands to provide the platform that customers actually need in that market.”

Compared with Jana’s, Brandtone’s technological approach seems relatively low-tech. Instead of a mobile website, it mostly reaches its customers via text messages and voice call. This is necessary, says Fitzmaurice, because the average user in emerging markets is on a “three year old gray-market Nokia that only does voice and text.” But Brandtone combines this technique for reaching mobile subscribers—which will be in the “top 11 developing and emerging markets in the world by 2013,” says Fitzmaurice—with teams of marketers in every country in which the company operates.

So in South Africa, for example, Brandtone set up a promotion that offered mobile-phone credit to anyone who bought a particular brand of washing powder. A code was printed inside each bag of powder, and buyers who texted the code to a certain number were called back with a recorded message from Nkanyiso Bhengu, a popular South African radio celebrity, followed by a three-question marketing survey. The promotion ran in six languages and reached millions of people.

Moreover, while Jana has most of the emerging world covered, it isn’t present at all in rich countries. That part of the world is the preserve of firms like Velti, a 12-year-old, publicly-traded mobile advertising firm based in the US. Whereas Jana and Brandtone tend to focus on cheaper phones, Velti sends 75% of its ads to apps on high-end smartphones and tablets, because that’s what rich-world customers are using.

But Eagle seems to have a different set of ambitions. His ultimate goal for Jana, he says, is to divert a significant chunk of the $200 billion that consumer-goods companies spend on advertising in the developing world into consumers’ pockets. These firms are betting that a consumer just coming into the middle class is going to be worth a lot of money over the course of her lifetime. Companies like Unilever, which makes most of its money in emerging markets, want a service that can connect them with customers all the way from asking them questions in marketing surveys to giving them coupons to following up with them after they buy.

“We have built a technology that can add value to lives and increase disposable income, and ultimately the goal is to have users cut their mobile spend in half,” says Eagle. For people in the developing world who are spending a tenth of their income on mobile service, that represents a 5% raise—good both for them, and for the companies that sell to them.

Next: read why people people can’t be bothered to use their smartphones to pay for things.