A deep-seated anxiety afflicts modern life, and it makes a picture like this go viral.

Some of the tirade is against technology, which many claim stops us from making connections with each other. The bigger worry is that, in our attempts to capture memories that we fear may be lost forever, we don’t live in the moment.

Morris Villarroel, professor of animal behavior at the Polytechnic University of Madrid and a life-logger, might have a solution. He claims that, with the help of a notebook to log everyday things and a camera attached to the chest that takes a picture every 30 seconds, his experience of life is more fulfilling and his memories richer.

“When my wife says ‘August just flew by, didn’t it?’ I say that ‘No, it didn’t.’” Villarroel told me at the Quantified Self conference in Amsterdam recently. “I remind her about the holiday we had, the park we went to, the wonderful dinner we enjoyed and so on. And suddenly August doesn’t seem to have gone by so quickly.”

Since 2010, for every day of his life he has made notes in 60-page Muji books. He has filled 180 of them, and wrote down an estimated 1.5 million words. He’s recorded almost every meal he’s eaten, person he’s met, event he’s attended, book he’s read, and even more that I’m not privy to.

He wasn’t sure initially whether he would be able to keep up the activity. But the longer he continued putting down his everyday life in words, the more he found it useful and the more he felt motivated to continue.

“Both my parents are psychologists and in my childhood, dinner table conversations often were around reflecting on thoughts,” Villarroel said. “I’ve had a lingering aspect of thinking about thoughts and feelings, and how thinking and talking about them can change over time. That is perhaps why I’ve always liked writing things down.”

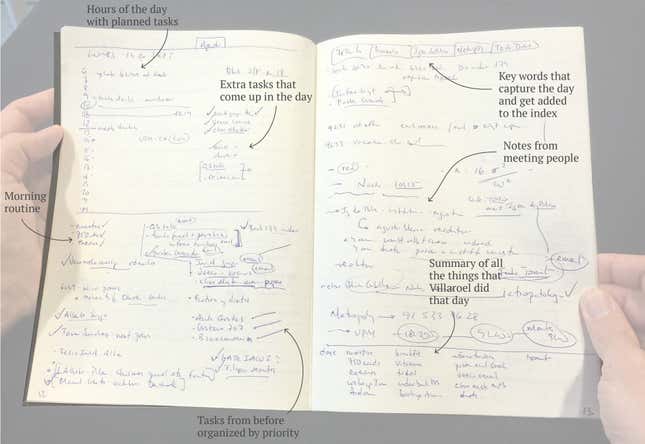

The log book has evolved over years, but here is a typical start to a day in the current form:

A day can fill two pages or 12, Villarroel said, depending on the kind of activity that’s taken place. He uses it for everything, even planning his science experiments.

Each log book has dedicated space for certain things. The inside cover is a two-year, annotated calendar that tells him at a high level how the days ahead look. The first page is for every meal eaten (even snacks), the second page for ideas, and the third page for a weekly calendar with a more detailed view.

Because the log book is not digitized, Villarroel has developed a system to make it searchable. In the back, there is an index which has keywords from each day (which you can see on the top of the right page of the log book). These can be about people, locations, objects, or actions.

Why life-log in the first place?

Villarroel’s life is complicated. Now, he is happily married, but has had five children with three different women. When he began his log book, he had just met his current wife.

“I didn’t start keeping the log book seriously until I turned 40,” Villarroel said. “It was a time where I needed a period of assessment.” And keeping a record of his thoughts was a way to manage what he said was a “chaotic life between his children and work.”

Adding more texture

In 2013, at the Quantified Self conference, Villarroel heard of a wearable camera that could capture even more of his life. He decided to get one.

Since April 2014, when Villarroel finally got his hands on the Narrative camera, he has built a growing library of more than 700,000 photos. They are snapshots of his life, captured every 30 seconds for 12 hours every day from a discreet camera attached to his shirt.

The idea of capturing life passively is not Villarroel’s. Digital pioneers have been doing it in one form or another since the 1990s. For instance, one of the first people to start this, Thad Starner, is now a lead designer of Google Glass.

But Villarroel, as far he knows, is the only person who does both with such dedication. Together they form a powerful combination: daily logging—a slightly more sophisticated form of journaling—helps plan for the future and then captures information after things have happened; and the life-logging camera captures things as they happen.

These two recording apparatuses help him capture different things The journal is a filtered analysis of some visible but many invisible things. The Narrative camera captures whatever the camera can see without prejudice.

Most importantly, they allow him to live in the moment: the camera captures images for posterity and the log book is filled later as a way to reflect. Villarroel reviews his log book when he has time, and the images from the camera once a week on the weekend. And he finds the process of reviewing very satisfying.

But Villarroel is also a numbers guy. He wanted more objective proof that all his effort was actually worth it. Perhaps he could even spot benefits he wasn’t aware of. So he decided to run an analysis. He chose 10 days at random and analyzed what the log book and the camera told him about those days.

On a spreadsheet, for each day, he counted the number of objects, people, actions, and locations that both the apparatuses had recorded.

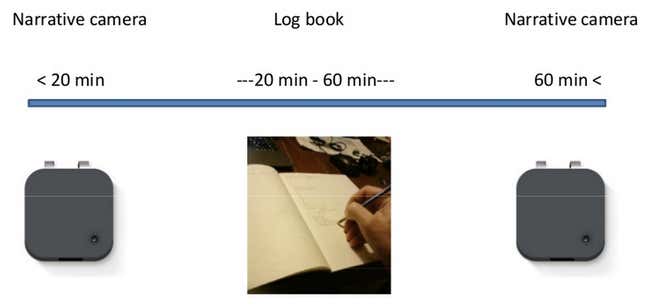

When he delved deeper, he realized that there was a pattern to the kinds of things captured beyond their categories. The log book was catching “events” that lasted between 20 and 60 minutes, where as the camera was capturing those at the other extremes.

For example, the camera captured a meeting with a colleague in the office corridor, but that didn’t make it in to the log book. Or the log book captured a 30-minute task completed on the computer, but the camera missed that.

The result, as he had suspected, was that the combination was helping him capture more of his day. The log book allowed for reflection and the narrative camera added texture to the reflection.

The power of introspection

There is some scientific evidence of the benefits of Villarroel’s practice. “The experience is consistent with mindfulness practices, which have been shown to have great benefits,” Ronald Riggio, a psychologist at Claremont McKenna College, told Quartz. “The perception of time, however, is subjective.”

Although Riggio was fascinated to hear of Villarroel’s experiment, the limitation that the experiment involved only one person means he can’t be sure whether others could benefit from it.

“But introspection and reflection are power tools in psychology,” he said. “There is a possibility that when you are more mindful, you may perceive that time goes slowly.”

Is the effort worth it? “Perhaps,” Riggio said. “This kind of daily activity requires a lot of dedication, but maybe once you form a habit it gets easier.”

Today we capture much of our life through email, calendar, private documents, tweets, Facebook posts, or Instagram images. But how much of it do we actually return to and reflect on?