China is a bachelor nation, with some 33 million more men than it has women to marry them. The glut of “bare branches,” as these arithmetically unmarriageable men are called, will only begin ebbing between 2030 and 2050.

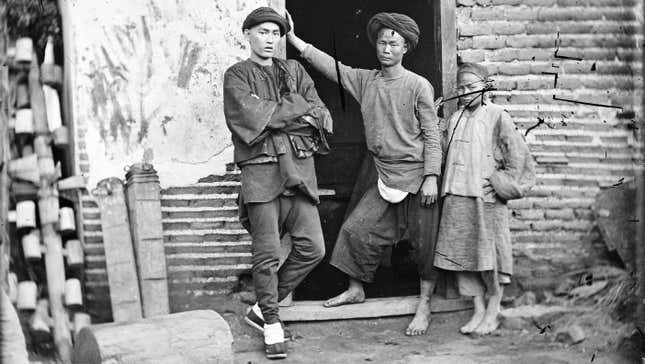

Though the term “bare branches” might sound like modern slang, it actually dates back centuries. That’s no coincidence—from 1700 well into the 1900s, China experienced a similar guy glut.

In fact, in 18th and 19th century rural China, women took two (or sometimes more) husbands. This happened in every province in China, and for the most part, their communities tolerated or even accepted it.

The little-known prevalence of polyandry comes to light in Matthew Sommer’s fascinating history of peasant family structures, Polyandry and Wife-Selling in Qing Dynasty China. Since most peasants were illiterate and the Qing elite regarded polyandry as supremely immoral, there are few traces of the practice. Sommer, a Stanford University historian, draws descriptions from court cases.

Take, for example, the story of a farmer named Zheng Guoshun and his wife, Jiang Shi, in the southern province of Fujian in the mid-1700s. When Zheng suddenly went blind, his wife recruited a younger man named Jiang Yilang (no relation) to move in with the couple and help out on the farm, in exchange for sex. For nearly three decades, relations among the trio seemed to have gone smoothly, and Jiang Shi bore two daughters. When Zheng died of natural causes, 28 years after the arrangement began, Jiang Shi and Jiang Yilang continued their relationship.

Though the Zheng-Jiang-Jiang union did happen to be the longest-term polyandrous relationship Sommer found, the story is hardly unusual. Some polyandrous relationships combusted after a few months (often ending in a crime that landed them in the legal record). But many endured for years or even decades.

So why take two husbands? Contrary to modern-day associations with polyamory, the purpose was to protect the family.

Given how hard it was for peasants to survive, this was no easy feat to pull off. Between 1700 and 1850, the Middle Kingdom’s population tripled in size. Cultivated farmland, however, only doubled—encouraging people to simply work the land even harder. That left more people depending on less productive land for food. Mass famine was common.

Meanwhile, thanks to female infanticide and the Chinese elite’s concubine habit, among other things, the Middle Kingdom was amidst a ”marriage crunch,” as demographic historian Ted Telford put it. The scarcity of demand meant rural men had to pay a heavy bride price—steeper than most could afford. The value of women’s sexual attention, companionship, and child-bearing capacity rose too.

When disaster struck—be it flooding or crop failure, or the personal calamity of injury or illness—two-worker families often earned too little to eat. Some families opted to sell of their children or allow a wealthier man buy the wife.

Instead of having to hock her kid or put the wife on the market, a family could find a second husband to bring in extra income and let families pool resources more efficiently. The primary couple gained economic security from this arrangement, while second husbands got a family and, often, the chance for offspring to care for them in their old age.

Many of these relationships were formalized according to local marriage custom. Some signed a contract, even though it was inadmissible in the Qing court. The two husbands commonly swore an oath of brotherhood (possibly in a bid to protect the first husband’s ego).

Exactly how common was the practice? It’s impossible to know. Since the Qing elite condemned the practice—while at the same time celebrating polygyny—many polyandrous families weren’t always open about the “uncle” living in the spare bedroom. Sommer notes that for every case recorded in the legal records of the time, there “must have been a great many others that left no specific written record.”

Not all of these unions ended well—in fact, many were recorded at all because one spouse wound up murdering another. But there’s a bias here: the literate people in the Qing only recorded their own, very different lives. So it’s impossible to know how stable the relationships were that didn’t end in tragedy, followed by a Qing courtroom. Despite this somewhat sordid skew, what comes through Sommer’s record of polyandry is how resilient these unorthodox families were.

Of course, this example will be of little help to today’s “bare branches.” In pretty much all modern states, polygamy of either sort is deemed threatening to marriage. Polyandry’s prevalence in Qing China, however, suggests that sometimes the way to strengthen a marriage is to make it a little bit bigger.