If you subscribe to Playboy, you’ll no longer need to hide your magazines under the bed. The New York Times reports that starting next March, the company will cease to publish nude photographs of women.

The decision marks a landmark shift in direction for the publication, which became a cultural touchstone for its trademark mixture of racy images with top quality journalism.

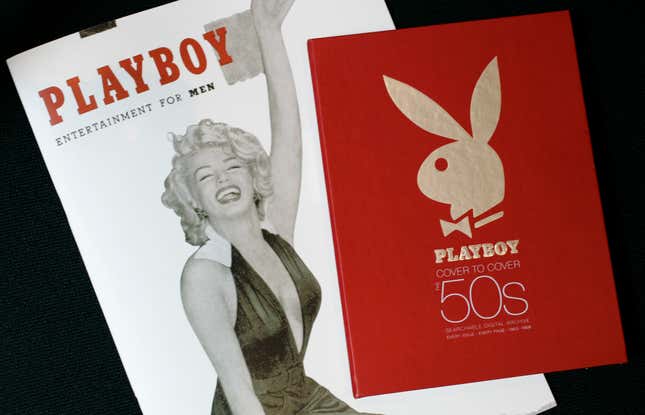

The very first issue in 1953 featured a nude photo spread with Marilyn Monroe, taken before she became a star, and laid out a commitment to meshing curves with class that helped elevate Playboy beyond the realm of mere smut.

As the first issue explained:

Most of today’s ‘magazines for men spend all their time out-of-doors, thrashing—through thorny thickets or splashing about in fast flowing streams. We’ll be out there too, occasionally, but we don’t mind telling you in advance—we plan on spending most of our time inside. We like our apartment. We enjoy mixing up cocktails and an hors d’ouevre or two, putting a little mood music on the phonograph, and and inviting a female acquaintance for a discussion of Picasso, Nietzsche, jazz, sex.

Throughout the sixties, seventies, and eighties, Playboy published fiction from Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Ian Fleming, and Raymond Carver, just pages away from scantily clad models and celebrities. In some cases, a Playboy photoshoot helped emerging stars grow even more popular, as was the case for Jenny McCarthy, who went on to become a 90’s cable TV staple after appearing in the magazine.

Now, though, naked photos are “passé” the company’s CEO told the Times. With free pornography of all types just clicks away, and magazine advertising plummeting, Playboy has lost its main selling point and a profit center. The magazine’s circulation dropped from 5.6 million in 1975 to just 800,000 today, the New York Times reports, citing the Alliance for Audited Media. Lackluster sales led Hugh Hefner, Playboy’s robe-clad founder, to de-list the company in 2011 at a $207 million valuation.

Cory Jones, an editor at Playboy responsible for the brand’s re-embrace of garments, said he hopes a gentler, hipper image will appeal to male urban millennials. He references the current enfant terrible of publishing as a partial inspiration: “The difference between us and Vice is that we’re going after the guy with a job,” he told the New York Times.