San Salvador, El Salvador

Juan José Gómez is exhausted. As one of 12 funeral directors working in San Salvador, he is on call 24 hours a day, seven days a week. On a humid Monday afternoon, he waits outside the city morgue, cell phone in hand, waiting for a tip-off from police or paramedics. “I’ve got connections”, he says with a wink. “Whoever arrives first on the scene, gets the job”.

A bloody rivalry between two gangs—Mara Salvatrucha (known as MS-13) and Barrio 18—has pushed the murder rate to levels not seen since the 1980s civil war. El Salvador has now overtaken neighboring Honduras (pdf, in Spanish) to become the most homicidal country on earth, not counting war zones. Having recorded 4,930 murders (Spanish) in the first nine months of this year, it’s on course to finish 2015 with a homicide rate of 102 per 100,000 inhabitants, more than 20 times that of the US.

The city’s police wear balaclavas to avoid recognition—some have had their families targeted after being identified by the gangs. Locals are killed for being in the wrong place at the wrong time, or for wearing the wrong clothes or sneakers (MS-13 sport Adidas Superstars; Barrio 18 Nike Cortez).

And as a result, the funeral business is booming. “The cheapest service we offer is $300, but it can rise to $2,000 depending on how much work needs to be done”, Gómez says grimly.

Beyond the heavily protected gates of the morgue—officially, the Institute for Legal Medicine—pathologists in pea-green gowns bustle from building to building. “Jesus Trusts In You” reads the sign above the double swing doors that lead to the autopsy room. Inside, five bodies lie on steel gurneys, wrapped in white plastic bags. One is lumpier than the others. “They chopped him into pieces”, says Raymundo Flores, a forensic technician. “They sawed his body around the neck, arms and waist.” Flores has worked in the morgue for 21 years. “I’ve seen it all,” he says, darkly.

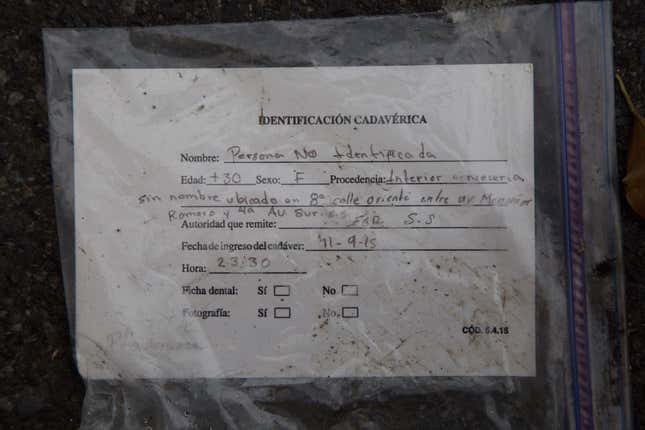

Once the autopsy is complete, the bodies are wheeled out and placed in a large bank of refrigerators. One side is reserved for corpses discovered not long after death, while the other is for those in a more advanced state of decomposition. Each is labelled with the victim’s name (if known), age, and the location where the body was found. The victims’ clothes are removed and placed in an industrial drier, to prepare them for use as evidence. In the corner a stack of jars filled with formaldehyde contain specimens which pathologists keep for further reference.

Raymundo Sánchez, a forensic anthropologist, works with the corpses in an advanced or total state of decomposition. Often killers will help locate the corpses of their victims in return for a reduced sentence. “Quite often we only find pieces of the body,” Sánchez says.

He and his team use dental records to try and identify victims. They also speak to families who are desperate to find and trace of their loved ones. “We interview mothers looking for sons. It’s very hard when they ask me, ‘Have you found my child? Have you found anything?’”, he says, sadly. “Families are being ripped apart.”

Staff are overwhelmed by the sheer quantity of corpses. Bodies left uncollected are buried in an unmarked grave on the edge of town. With the morgue running at full stretch, in August staff had to place an emergency order for the plastic bags used to shroud the bodies. In September the morgue’s director, José Miguel Fortín, told reporters that his employees are “going crazy” with the amount of work they are being asked to do, describing the country’s gang violence as “a national emergency.” “Only those who use bulletproof cars are safe,” he said.

Gómez’s business is doing well. His funeral company, Luz Funeraria de Israel, makes around $8,000 a month. Half of that covers his costs and the wages of his six staff.

It’s not a bad profit margin, but it doesn’t begin to compensate for the risks. After attending the scene of the crime, Gómez has to track down the victim’s family—to break the bad news and to get their business. Driving through gang-controlled neighbourhoods, he risks being confused for a rival gang member, or an investigator. Twenty undertakers have been killed across the country so far this year.

Outside the morgue, the victims’ relatives wait patiently to collect their bodies. “There is no justice here,” spits Mariana de Jesús Martínez de Contreras, “only impunity.” A week earlier her son Juan Carlos had been playing soccer in a neighbourhood on the flanks of Quetzaltepec, the volcano that looms over the capital. “Someone just came and shot him”, she says. “They didn’t know him, but they shot him in the head, neck and chest.”

Back at the funeral parlour, Gómez washes and embalms the body, working to make it as presentable as possible to the family. It can be a traumatic experience. He spends much of his time with the bodies of young men, many around the same age as his 15-year-old son. “Half of them belong to gangs but the other half don’t. Some are killed because they don’t want to be part of the gangs,” he says. Most show signs of having been executed—forced to kneel with their hands tied behind their back before being shot in the head. “I see a lot and it hurts”, he says, solemnly. “But I’m a witness.”