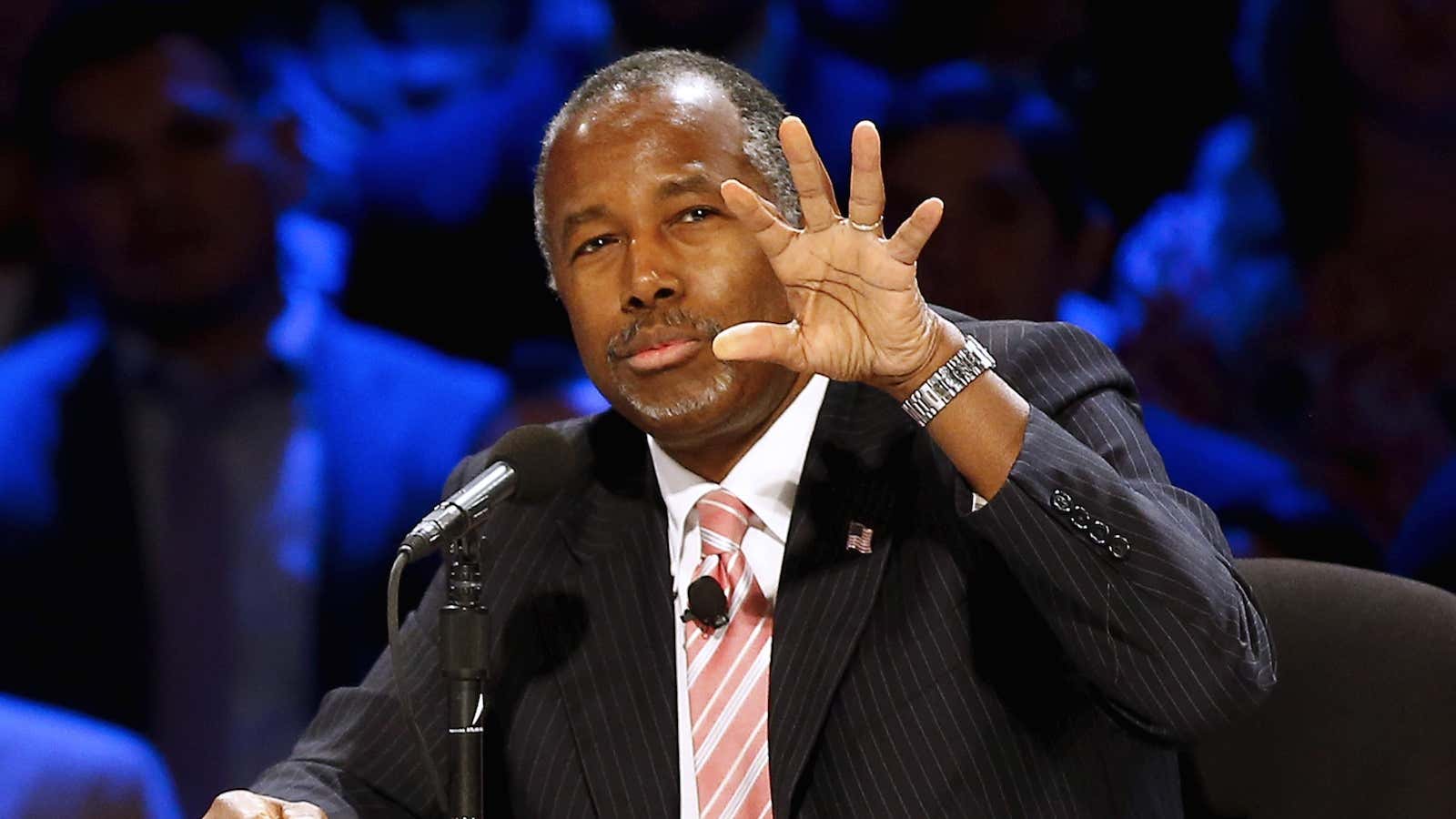

The numbers are in. Georgia’s newly instated Peanut Poll, which at 28,000 votes weighs in as the largest straw poll in the United States, has former neurosurgeon Ben Carson leading the conservative pack Oct. 19.

Though national polls still indicate that reality-television star and real-estate mogul Donald Trump is enjoying a lead as primary season approaches (though only by 3%, according to NBC and The Wall Street Journal), Carson’s substantial appeal among conservative voters is undeniable. And it has pundits and analysts on both coasts positively stumped.

“He’s appealing to a significant amount of Republicans,” writes Janell Ross, a reporter for The Washington Post who writes about race, gender, immigration, and inequality, but “they just might not be exactly the ones people suspect.” She breaks down the polling data behind Carson’s swift ascendance, debunking theories that he has been propelled solely by evangelical-Christian conservatives, or conservatives of color.

Ross insists Carson’s support base is too scattered to extract any discernible demographic pattern of preference—he appeals to Republicans of all shapes and sizes. This suggests the attraction is more general than candidates who have staked their electability on marquis issues (Trump on immigration, Carly Fiorina on Planned Parenthood, etc.). And this, of course, makes his popularity all the more difficult for the media and primary opponents to parse.

One theory relies on the ostensible strength of his outsider status. As a former neurosurgeon who has never held political office, he appeals to a broader dissatisfaction among conservatives with “career politicians” and “Washington insiders”—terms often pejoratively thrown at Democratic frontrunner Hillary Rodham Clinton, who has served as a first lady of both Arkansas and the United States, a senator from New York, and president Obama’s secretary of state. One-time Republican frontrunner Jeb Bush—former governor of Florida, younger brother to former president George W. Bush, and son of former president George H. W. Bush—has seen his numbers drop precipitously in the polls, perhaps as a result of voter fatigue with veteran politicians like himself.

But Carson’s campaign is largely run by definitive Washington insiders. His campaign manager, Barry Bennett, has worked for a slew of big-name legislators; and his senior strategist, Ed Brookover, is a three-decade veteran of the political communications-industrial complex. A quick glance at the rest of his campaign roster reveals a brain trust of political operators conservative voters outside the Beltway are convinced they loathe. He’s an “outsider” in name only; it’s establishmentarians who are orchestrating things behind the scenes.

There is also Carson’s race to contend with. As the only African-American candidate in the 2016 field, he no doubt reassures overwhelmingly white GOP voters that their opposition to groups like Black Lives Matter is not fueled by any sort of racial prejudice (an extension of the “I have black friends rationale.”) He’s a black man who only talks about issues important to black people when he’s minimizing them (i.e., “Of course all lives matter. I don’t want to get into it, it’s so silly,” as he remarked at a rally on Capitol Hill in August).

In that vein, Carson is the ideal candidate of color for a conservative voter—a superficial symbol of supposed antiracism. He’s not defined by the color of his skin, which his supporters probably appreciate—that is, until they are called on to disprove accusations of prejudice. Then, suddenly, his blackness becomes important.

The fact that these rationales are so flimsy yet nonetheless applicable probably says more about conservative voters than they do about Carson’s appeal. His soft-spokenness and overall flavorlessness, personality-wise, ultimately provide a kind of blank slate on which to project (hazy, unidentifiable) political frustrations.

Ben Carson is the conservative candidate for voters who don’t know what they want, who are too lazy to look beyond televised speeches or soundbites regurgitated by CNN and Fox News. And when he does speak with anything resembling forcefulness, it’s to offer bizarre opinions comparing the United States to Nazi Germany, and invoking the ghost of Adolf Hitler—always a sure bet in conservative America.

In a way, Carson’s popularity is demonstrative of the widening gulf between American ideological factions. Some have likened him to Bernie Sanders—a surprisingly popular, one-time fringe candidate who could direct his more radical partisans to support a moderate nominee assuming he doesn’t garner the nomination. But whereas Sanders’s supporters pride themselves on being intensely informed and skeptical of what they see and hear in the mainstream media, Carson’s supporters are looking for a security blanket. They want a candidate who will indulge their paranoia and latent prejudices rather than, say, the more cerebral Ted Cruz, who might force them to be cognizant about the reverberations of their vote.

Ben Carson is a people’s conservative candidate, to be sure, but the people in this case, despite apparent frustration with the status quo, haven’t got much will. They are exhausted by the politics of recent decades and the much-talked about “gridlock in Washington,” which might be why they support a candidate who seems to not want to think too much about anything at all.