We’re kidding—kind of.

Elon Musk’s auto company is ripping through cash at a prodigious clip, at times burning through roughly $100 million a month.

Given that the company has strung together 10 straight quarterly—not to mention growing—losses, that’s a recipe for incessant infusions of new capital.

No problem. At the moment the markets seem to more than happy to hand over the money that Elon Musk needs to build out the vertically integrated auto behemoth of the future. (The so-called gigafactory in the Nevada desert where Tesla will build advanced lithium-ion batteries is expected to cost around $5 billion.)

But some, such as Barclays auto analyst Brian Johnson, suggest that the market might not totally appreciate the scope of cash that would be needed to complete the build out of Tesla’s ambitions. In a research note today he wrote:

We believe it cannot be understated how radically retro Tesla is in its approach of vertical integration, an approach which was last embraced by Henry Ford 100 years ago. This approach differs from the current approach of other OEMs, who have a largely outsourced value chain (we suspect Apple may also pursue this strategy when it enters the auto business). Vertical integration comes with very capital intensive machining and engineering costs – e.g., for tooling, forging, casting, and product design functions. While Tesla believes vertical integration is a competitive advantage, it is also unquestionably a significant drain of cash. While Tesla is likely to significantly improve its capital efficiency per unit in the coming years, we suspect the market is under-appreciating how significant the cash burn will be through the end of the decade, and likely for the next ten years

Again, at the moment, there doesn’t seem to be much of a problem.

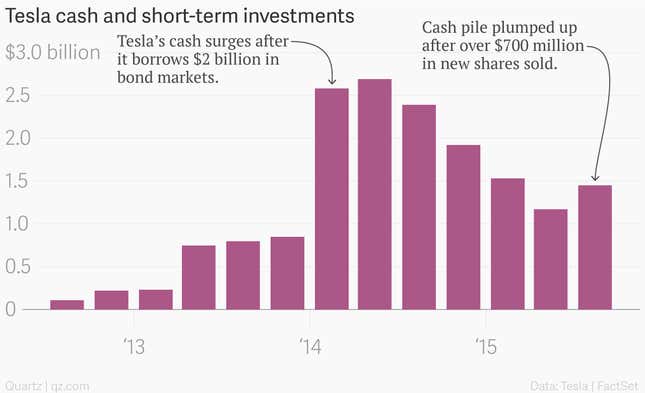

True, Tesla shares are no longer surging the way they were a couple years ago. They’re even down about 6% so far this year. But that’s far from an indication that investors have serious doubts about Team Elon. Moreover, the company has borrowed in excess of $2 billion since 2013, both in the bond market and through establishing lines of credit with banks. The company also raised more than $700 million by selling new shares in August. Given Tesla’s reception by investors, it’s hard to see why Tesla shouldn’t exploit this new—and seemingly inexhaustible—financial resource.

In fact, if anyone should be worried, perhaps it should be Apple’s shareholders. After all, Tesla is providing pretty compelling proof of just how expensive auto manufacturing would be. And Apple is also weighing entry into the world of capital intensive car production.

It’s one thing if shareholders at Tesla sign onto such industrial adventure. It’s another for Apple investors to watch the the company’s $200 billion pile of of hard-won shareholder capital potentially be eaten up by such an old school manufacturing effort.

Correction: An earlier version of this post said that Tesla’s ”gigafactory” will make both batteries and cars; it is only batteries.