A severed finger points to the difficulty that Paris faces after the terror attacks that killed more than 120 people on Friday. The finger belonged to Omar Ismaïl Mostefai, a 29-year-old of Algerian origin who was one of three suicide bombers to storm the Bataclan theater on Friday.

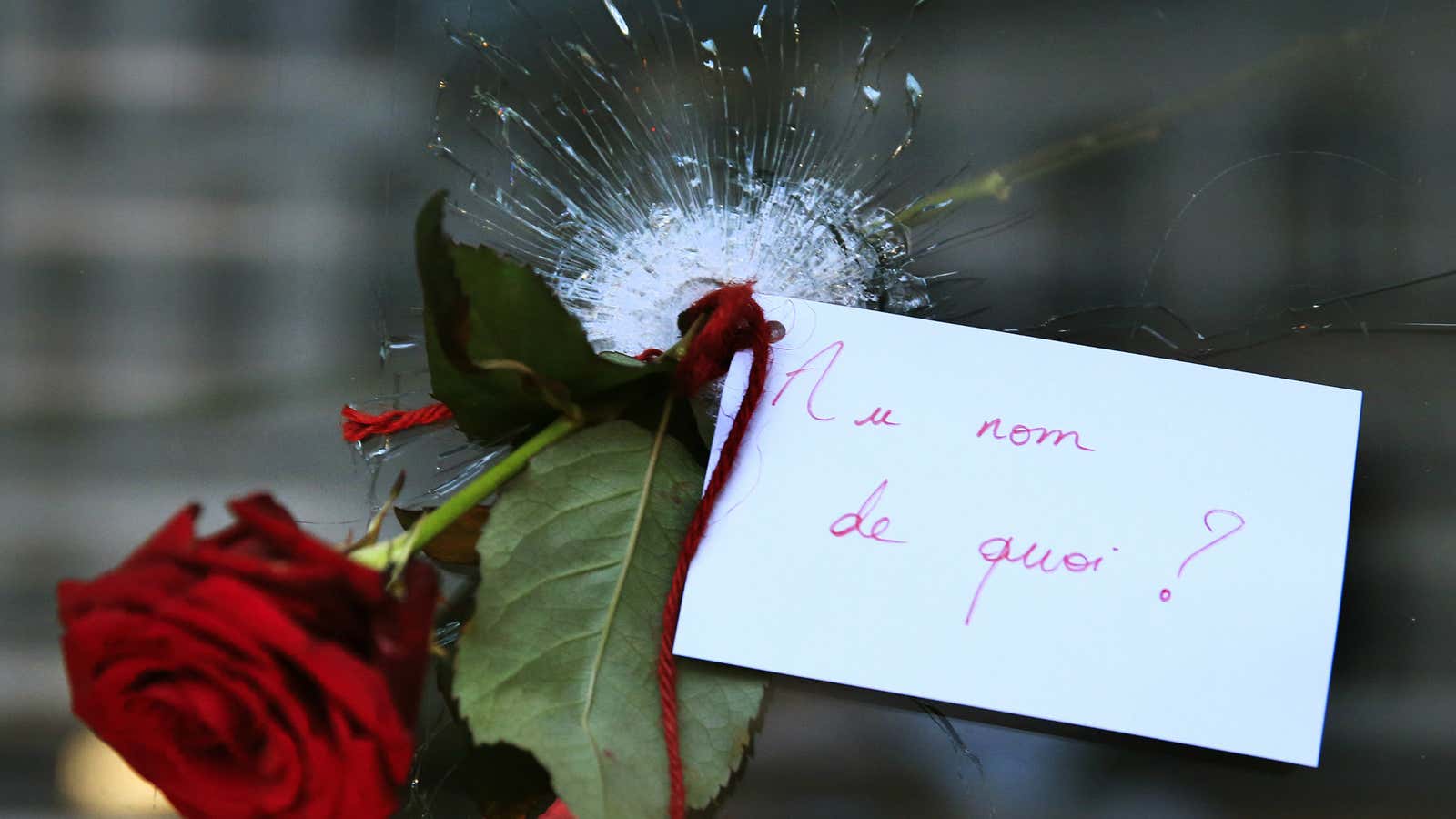

The attack confirmed the country’s worst fears over the radicalization of its own citizens, coming less than a year after Charlie Hebdo. And as the country reels from the news that the Syria-visiting Mostefai was known to authorities and arrests his friends and family, France is now moving on to questions of why the French authorities failed to prevent the attack.

Mostefai was on the so-called “fiche S” (link in French)—a government register of individuals who are suspected of being radicalized but have yet to perform acts of terrorism. The “S” stands for their potential to “endanger the security of the state.” The register is sub-divided into further categories, from S1 to S16, which encompass everyone from soccer hooligans to anti-globalization protesters. But S14 is the category that has the most attention at the moment—it stands for fighters recently returned from Iraq and Syria.

Prime minister Manuel Valls has now revealed that 10,500 people are marked under fiche S (link in French). Those on the list aren’t constantly monitored, as the register only serves as a warning to authorities. Mostefai’s name was renewed on the register as recently as on Oct. 12 (link in French), though authorities hadn’t had any concrete proof at that point that Mostefai was involved in terrorism.

It’s not just Mostefai. The Kouachi brothers that attacked Charlie Hebdo (link in French) as well as Ayoub El Khazzani, the man that attempted to carry out a train attack in France in August, were also all known to intelligence services. The French intelligence services are now under renewed scrutiny, with many questioning the usefulness—or limitations—of fiche S.

Former president Nicolas Sarkozy, who is seeking re-election, has called for those on the list to be placed under house arrest (link in French) and tagged electronically. ”All those who left for jihad and came back should be immediately put in prison,” he added. Sarkozy even added anyone looking at jihadist websites “should be considered a jihadist.”

France now finds itself embroiled in a debate on the ability of French authorities fight terrorism without compromising civil liberties, a debate that the West has been struggling with. Following 9/11, the US passed the controversial Patriot Act, opened and has been unable to close Guantanamo Bay, and has grasped with difficult cases like Jose Padilla’s—a US citizen declared an enemy combatant and imprisoned without trial by the US government for four years.

(The French passed their own version of the Patriot Act earlier this year.)

In the UK, the home secretary dismissed “airy fairy” fears over civil liberties after 9/11 as the government pushed for sweeping laws that allowed foreign terror suspects to be detained indefinitely without a formal public trial. That law was struck down by the country’s highest court in 2004.

It is worth noting, as this year is the 800th anniversary, that the Law Lords cited provisions against detention without trial in the Magna Carta (pdf), the ancient English document on rights that dates back to 1215, in their ruling. ”Indefinite imprisonment without charge or trial is anathema in any country which observes the rule of law,” one judge said.

This post has been updated with the number of fiche S suspects.