Chinese firms are buying control of a string of struggling US electric-car and battery makers—tarnished trophies of America’s exuberant but so far disappointing foray into the industry. But while critics assert that the Chinese shopping spree reveals the failures of US energy policy, it actually says more about how some of the world’s biggest fortunes of the last three decades have been earned: namely, thanks to a sharp eye for an unrecognized bargain.

Steve Jobs’ 1979 pilferage of the mouse from Xerox PARC, which led to the Macintosh computer, is perhaps the most famous example of such scavenger-hunting. (Here is a video of Jobs fessing up.) So it has gone in the battery business. US scientists have invented almost every major advance in contemporary batteries—alkaline (Lewis Frederick Urry), nickel-metal hydride (Stan Ovshinsky), and lithium-cobalt-oxide (John Goodenough). Yet it has been Japanese companies that have done the commercializing. Today, they dominate the battery market along with South Korean and Chinese companies.

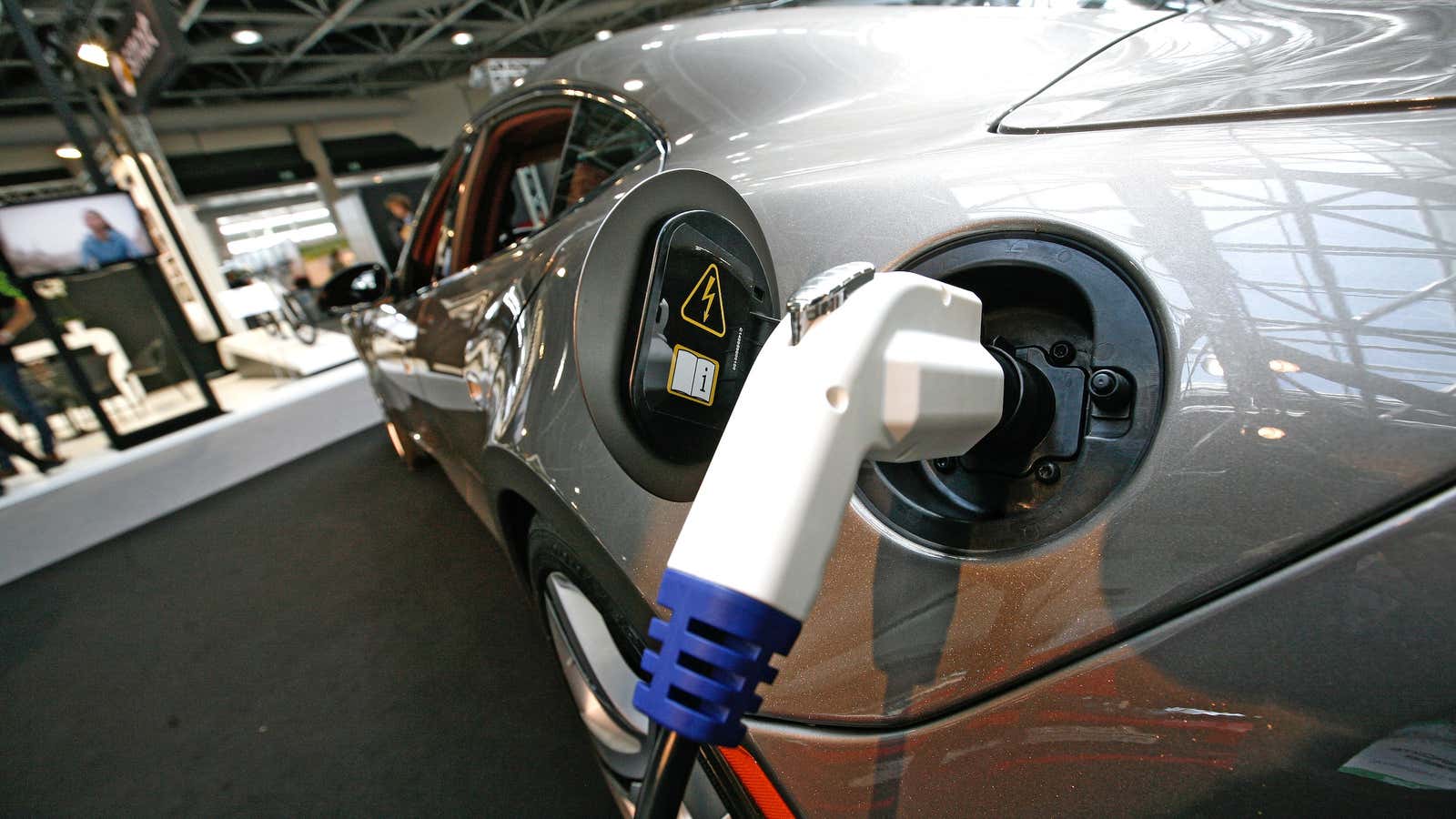

China is expressing its ravenousness

The companies China has snapped up are mostly the beneficiaries of large federal grants. This has gone over poorly in today’s aggressive political climate. One such firm, Fisker Automotive, the recipient of $193 million in US government loans, is examining two Chinese bids for a majority stake in the company—one of them from Geely, which already owns Volvo.

That comes after the US in January approved the sale of A123, which received $123 million in US government money, to Wanxiang Group for $257 million. Last year, Wanxiang made a $25 million investment in Smith Electric, which manufactures electric transport vehicles. And California’s CODA Automotive, along with its investor Lishen Power Battery, obtained a $394 million line of credit from a Chinese bank. (Hat-tip to Gigaom for collecting the data.)

This largesse goes back to then-president George W. Bush, who in 2007 linked electric cars with national security, and signed into law $25 billion in federal loans for carmakers, some of which went into electric-car development. Bush met in the Oval Office with the executives of A123, and gave the company a $6 million grant. President Barack Obama showered more than $4.4 billion on the electric-car and battery-makers.

The Fisker and A123 acquisitions have generated the most criticism. On Feb. 19, two US senators said Fisker’s technology should not be sold to Chinese companies.

The hyperbole bubble has burst

Batteries and electric cars have experienced a global hyperbole bubble over the last four or five years. There was much confidence in Europe, Asia and the US that the cars were on the cusp of a commercial breakthrough. But few motorists turned out to be willing to pay more just to feel green. Similarly, there was excessive confidence that scientists could quickly invent improvements to make electric cars substantially cheaper.

On top of that have been public-relations setbacks. Most recently, authorities grounded the Boeing 787 Dreamliner because of smoke and fire problems attributed to its lithium-cobalt-oxide batteries. On Feb. 15, Airbus said it will drop lithium-ion batteries in its next jet, the A350, in favor of heavier, workhorse nickel-cadmium batteries (which were invented in 1899).

Now comes the smart strategy

So why is China so interested in these American firms? Because it has a smart long-term strategy. Facing the same reality as the rest of the world—laggard technological development and consumer demand—Beijing has stretched out (paywall) its goals to give it more time to own the enormous electrified market it believes is coming.

To get there, it will have to eclipse Japan, which is by far the world leader. Japan achieved first-mover status in 1991 with Sony’s commercialization of the lithium-ion battery (using a combination of American patents by John Goodenough and Bell Labs). Then, Toyota launched the hybrid Prius in 1997, and now expects to sell 1 million of the vehicles this year and next (paywall). South Korea, which has seized the lead in other products that Japan once dominated, such as big-screen TVs, is likely to challenge Japan in electrified vehicles as well.

But China’s acquisitions attest to the fact that America still has an advantage in both pizzazz and pure research muscle. Elon Musk’s Tesla continues to dazzle as the world’s sexiest electric car, despite controversy over its potential. And on Feb. 7, outgoing US energy secretary Steven Chu announced a five-year, $120 million joint government-industry initiative to make a big, next-generation breakthrough in advanced battery-technology.

All of these rivals are waiting for a big leap in the laboratory that will make batteries cheaper and more powerful. Until then, most of the action will be in marketing, design, sharp practices in mergers and acquisitions … and of course, politics.