This is quite literally a very big deal.

The merger announced today between drug giants Pfizer and Allergan is valued at roughly $160 billion—or $146.5 billion if you exclude the debt portion of the deal.

Not only does that trounce Anheuser-Busch InBev’s announced $117 billion purchase of SABMiller earlier this year, it is the second-largest deal of all-time.

The biggest was British telecom giant Vodafone’s takeover of Germany’s Mannesmann in 2000. That merger clocked in at $172 billion, when it was announced back in 1999, according to market research firm Dealogic.

(For the record, these figures aren’t inflation-adjusted. So the Vodafone-Mannesmann deal would be something like $245 billion in today’s greenbacks.)

So what’s the business rationale for this large-scale redeployment of capital? Untapped consumer markets? Technological synergies that could speed new, profitable, socially valuable new drugs to market?

All that remains to be seen. But one thing is clear. This is financial engineering at its finest, helping Pfizer lower the amount of tax it pays to the US government.

According to the Wall Street Journal this would be the largest ever tax inversion, a specific type of deal that allows a US company to move its headquarters abroad in order to benefit from a lower corporate tax rate. The Journal reported that by merging with Allergan—which is based in low-tax Ireland—Pfizer could cut its tax rate to less than 20% from its current 25%.

Earlier this month, the US Treasury Department announced new rules aimed at clamping down on the practice. But Treasury secretary Jacob Lew said there was only so much the Treasury Department could do to stop such deals, without additional legislation from Congress.

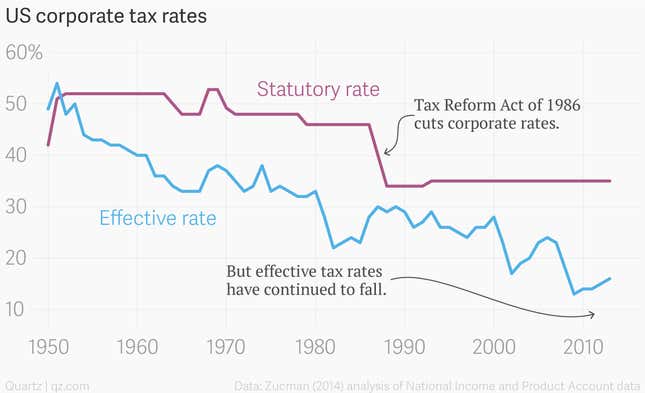

Critics of the US tax system say its corporate tax rate is simply too high, at a statutory 35%. (Ireland’s is 12.5%.) But few US companies actually pay 35%.

In fact, the effective tax rate—a fuzzy figure that shows what corporations, in theory, would be obligated to pay, if they repatriated certain portions of earnings made abroad (which many don’t)—has been steadily declining to 20%, according to French economist Gabriel Zucman.

Zucman, who studies tax avoidance, suggests the decline shows that companies have become increasingly efficient at skirting tax laws. The rash of inversion tax inversion deals over the last couple years would seem to reinforce his point.