Before the introduction of the euro as a continental currency, euro zone nations agreed in 1997 to the Stability and Growth Pact, setting limits on member countries’ debt and deficits based on each nation’s GDP. The agreement stipulated that the signatories keep their debt below 60% of GDP and their deficits under 3% of GDP. Some nations have met the requirements every year. Most have not.

The Council for Economic and Financial Affairs, a body including finance ministers from every member nation, is the only organization permitted to sanction out of compliance nations. It has never done so.

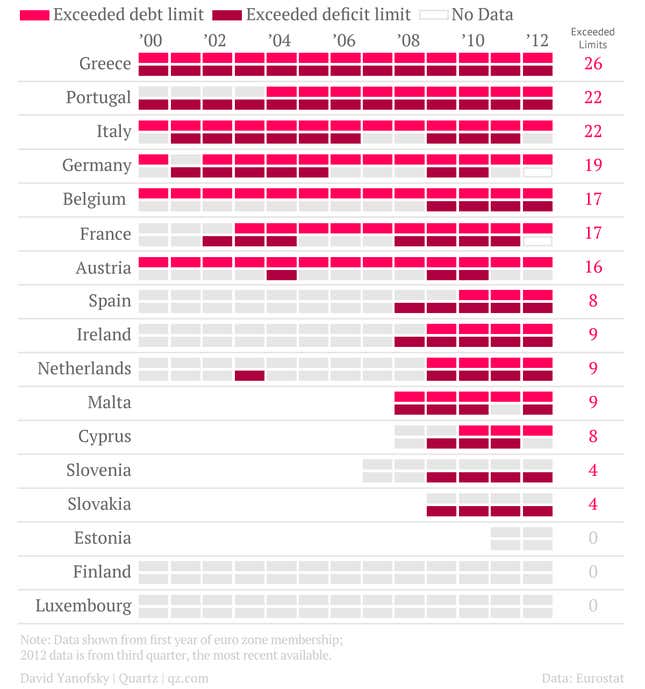

Here’s an illustration of how many times each country has exceeded one or the other of these limits:

Luxembourg, Finland and Estonia are the only nations to meet both requirements every year of their euro-zone membership (though Estonia, to be fair, has only been in for two years). Greece has never met either requirement. Five other nations—Portugal, Italy, Germany, Belgium, and Austria—have never met both requirements in the same calendar year.

The body charged with monitoring the limits estimates that this situation is not likely to change soon. On February 22, the European Commission released projections for the next two years that forecast 10 countries–Greece, Portugal, Belgium, France, Spain, Ireland, the Netherlands, Cyprus, Slovenia, and Slovakia–exceeding the deficit limit in 2013, and 9 countries exceeding it in 2014.

Europe’s inability to observe or enforce its self-mandated fiscal restraint hasn’t been worrying global markets as much as it used to. Since August, investors have been driving euro zone nations’ bond yields lower, reaching levels similar to 2010, revealing a confidence in the nations’ commitment to servicing their debt.

Looked at in aggregate, the euro zone is better at meeting its limits. Since 2000, the combined euro zone has only exceeded budget deficit limits four times, three of them in the last three years.