This item has been corrected.

MUMBAI—India has the world’s largest mobile phone market after China. Yet the amount of money mobile networks make per user is among the lowest in the world: around $2 per month. Chinese carriers such as China Mobile make five times as much. AT&T rakes in $65 per user per month in the US.

The most obvious reason is that Indian carriers operate on razor-thin margins, charging customers $0.01 per minute. Smartphone users spend more but penetration remains low. Half of Indian smartphone owners don’t have a data plan anyway, according to Prashant Singh of Nielsen. But there are other things that make India unique.

Unlike many markets, Indian carriers derive most of their revenues the old-fashioned way: from people making calls. Non-voice revenue is just 11% of the total. That’s about half as much as in Britain and just under a third of American and Chinese operators’ non-voice revenues (pdf). Only one in two Indians send text messages, much lower than the 62% in its class of what the World Bank defines as lower-middle-income countries. Considering the zeal with which Indians have taken to mobile phones, what explains their reluctance to embrace their use for other things?

A big obstacle is language (bhasha or vasha in Hindi). Most phones sold in India come with English-language operating system software. Despite India’s reputation as an Anglophone nation, only a tenth of its 1.2 billion people count English as their first, second or third language. In any case, one out of four Indians cannot read or write. But unlike linguistically homogeneous Russia or China, India’s 22 official languages (and several hundred unofficial ones) in 11 different scripts make it a difficult market to crack.

As a result, carriers looking to flog extras, or “value-added services,” are forced to interact with their customers through automated verbal instructions. Bharti Airtel, India’s largest network, earlier this month introduced “Apna Chaupal” (“our community center”), a voice-based marketplace for value-added services such as cricket scores and prices for produce. According to the press release, Apna Chaupal is “especially designed for the rural and semi-urban market.” That makes sense: more than 70% of Indians live in rural areas. Yet only 38% of subscribers (pdf) are to be found in its villages.

The effect of English-only input may affect voice revenues too. Abhijit Bhattacharjee, a retired army signals engineer and founder of Panini Keypad, a multilingual input app, cites the very real example of domestic help who ask for assistance in feeding in numbers into their phones. Bhattacharjee suggests that if people were able to add names to their phonebooks, they might make more calls. As it stands, illiterate and non-English-speaking users tend largely to call numbers they have memorized.

A few phone-makers, notably Nokia, have tried adding Hindi, India’s most widely used language, to their operating systems and physical keypads. It didn’t catch on, in large part because with three dozen consonants, 10 vowels, assorted symbols and innumerable combinations thereof, Hindi is not very user friendly on just 12 keys.

Hindi is only one of India’s many languages. To produce phones for every one would be madness. To not would be to miss the point. (Neither Nokia, Samsung or India’s Micromax responded to requests for comments.)

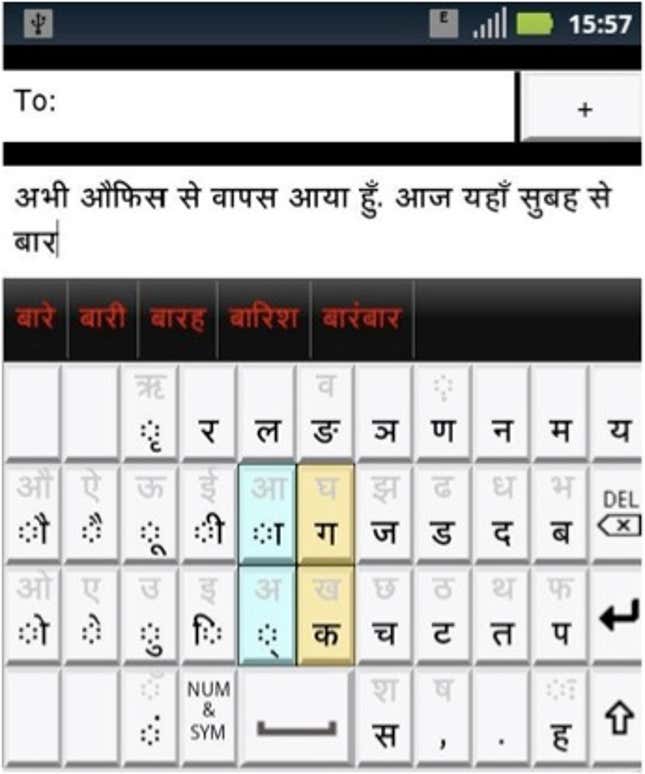

Bhattacharjee’s solution is ingenious. Panini Keypad, named for a Sanskrit linguist, turns the screen into a virtual keypad corresponding to the 12 buttons on older phones. After a user types in the first character of a word, the phone displays a set of letters in a 3×4 grid corresponding to the keypad. An algorithm picks the characters it thinks will most likely come next, based on a corpus of literature from that language. Instead of clicking repeatedly until the right character is displayed, the user can pick one from that set or go on to the next screen. The first phone embedded with Panini shipped earlier this month in Bangladesh.

Another start-up, Reverie, has grander ambitions. Its founders, who between them have 40 years of experience working with language and computing, are tackling the problem from every angle. Reverie makes fonts for better local-language rendering, produces virtual keypads for input and is working with carriers and manufacturers to embed its software into chips and handsets. Arvind Pani, Reverie’s co-founder and CEO, points out the overwhelming majority of print and television consumption in India does not happen in English, making mobile a strange anomaly.

Bhattacharjee and Pani are hardly the first people to cotton on to this. The government funds the Technology Development for Indian Languages program as well as the Center for Development of Advanced Computing, which works on multilingual computing (and where Pani’s co-founders worked). Last year, the Indian arm of the World Wide Web Consortium ran a conference focusing on language and the mobile web for cellphone networks and manufacturers. And IBM has long been working on a spoken web project in India. Yet none of these efforts has so far led to mainstream use.

The problem, says an executive from one of the top three carriers, is one of misaligned incentives. Telecom companies have the most to gain from users sending more texts and buying more value-added services. But mass adoption of services like Panini or Reverie depends instead on the device manufacturers to ship the phones with language support built in. “But they are not keen on doing it and we cannot make them do it,” he says.

With India’s subscriber base declining for the first time—though that is partially a result of networks trimming inactive users—the need for growth is rapidly becoming apparent. Just as the proliferation of mobile phones created hundreds of thousands of jobs and spurred the creation of an entire industry for ancillary services, an explosion in value-added services would benefit entrepreneurs and startups too.

India is often cited as a place where wireless telephony has changed life beyond all recognition. But the real mobile revolution is still to come.

Correction (Feb. 27): An earlier version of this article incorrectly named the founder of Panini Keypad as Abhijit Banerjee instead of Abhijit Bhattacharjee.