What does it mean when your child starts questioning authority and criticizing the government? Is it typical youthful rebellion? The awakening of a political conscious? Or a sign that he or she is on the path to violent extremism?

Parents in London have been warned that it could be the latter.

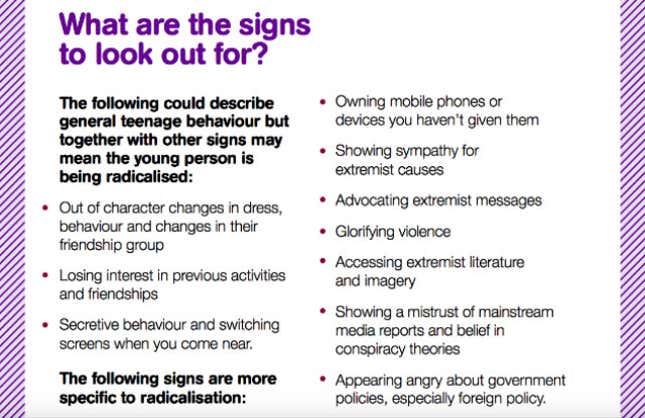

An anti-radicalization leaflet recently distributed by a local child protection agency cautions parents who are worried about their children’s ideology to be alert for signs of typical teenage rebellion: changes in friends, dress, or behavior; acting secretive when parents approach.

Then it lists other signs that could indicate a potential extremist in the making. These include: Mistrusting mainstream media reports, supporting conspiracy theories, and criticizing government policy, particularly foreign affairs.

Those characteristics are also typical of Alex Jones fans, but it’s pretty clear that’s not the kind of extremism the Camden Safeguarding Children Board is worried about.

UK civil rights groups have criticized the brochure’s apparent conflation of engaged citizens with terrorist sympathizers.

At the very least, the awkward language, similar to warnings issued in France in the wake of the Charlie Hebdo attacks last January, shows how difficult it is for programs and parents to effectively counter violent radicalization.

At least 700 Britons have traveled to join the conflict in Iraq and Syria. Most are believed to have joined the Islamic State. Many of them never did anything to draw the attention of UK security services before they left.

ISIL’s appeal to the British Muslims it has recruited from all walks of life highlights the failure of a key element of the UK’s counterterror strategy specifically designed to counter such grooming.

Preventing Violent Extremism—Prevent for short—has been an official part of the UK’s counterterror strategy since 2003. The program has struggled over the years to find effective programs and battle its own credibility problems.

After 12 years and more than £40 million ($60 million) in funding, the program is viewed with deep suspicion by many British Muslims, who see it as a government-sponsored effort to spy on and criminalize their communities.

This summer the UK government expanded the law to give school employees—along with those at prisons, hospitals, and local governments—a duty to report people who appear sympathetic to “extremism.”

Even before schools were included, UK public employees referred more than 4,000 British children to the government’s anti-radicalization program since 2012. Most were Muslim. The youngest child was 3.

“I feel I am being watched,” a British Muslim mother told the Guardian. “You worry that they could take your children into care.”