Italy’s newly elected politicians face an impossible task: lasting the full five years of their term.

And the only way forward might be to borrow a solution from the country’s recent past—a unity government like that formed in November 2011 amid a financial crisis and the resignation of Silvio Berlusconi—and then go through another election exercise.

All over again.

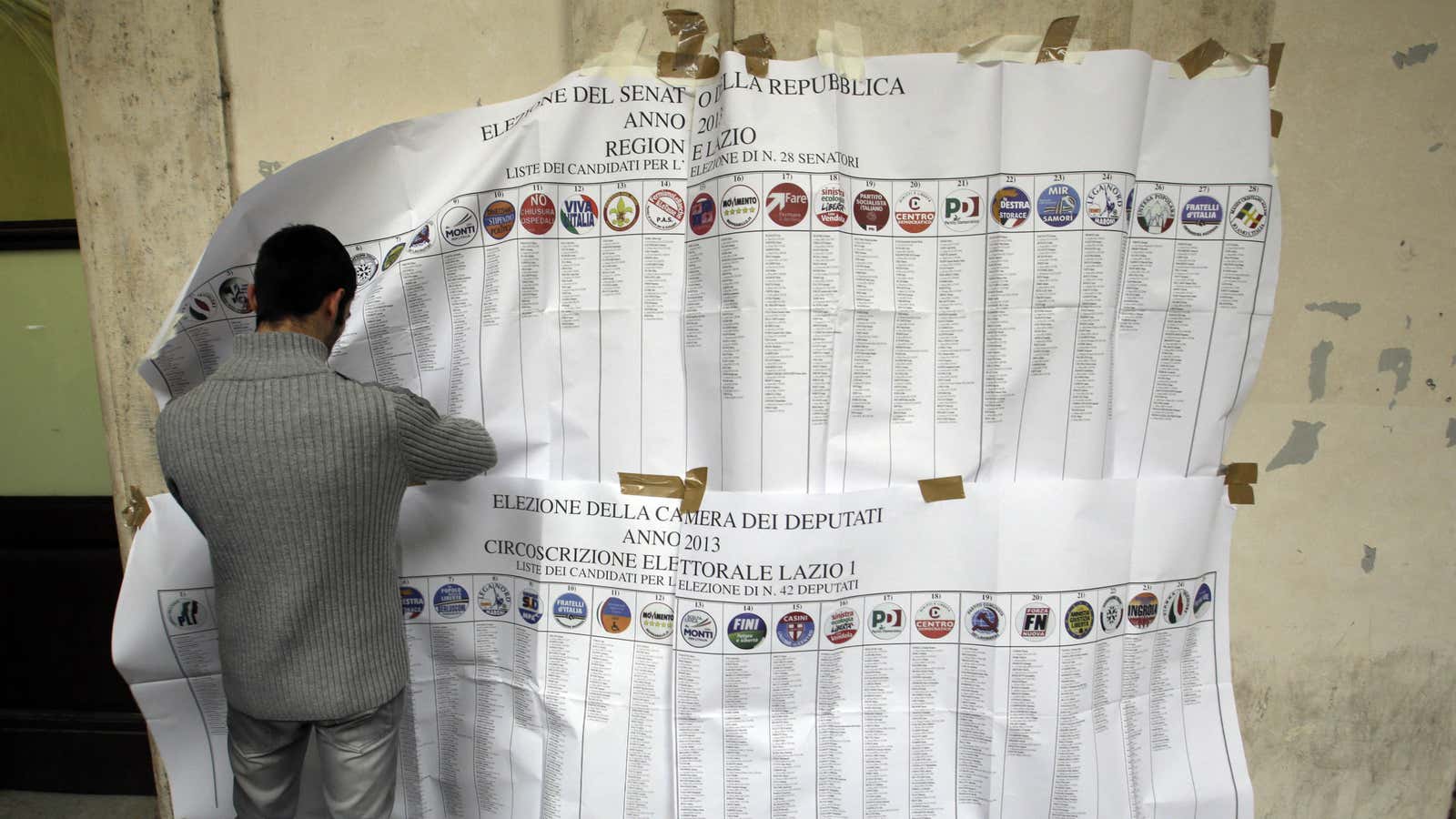

A flawed electoral law allocates different majority prizes in the Chamber of Deputies (the lower house, where the most voted nationwide coalition get the absolute majority of deputies) and the Senate (where power is allocated by region). The system thus hinders the formation of a stable majority, and so yesterday and today’s vote failed to deliver a clear winner in the eurozone’s third largest economy.

The way this played out in this most recent election: The center-left coalition led by the Partito Democratico’s (Democratic Party, PD) secretary Pierluigi Bersani is poised to prevail by a very narrow margin (less than 1%) in both houses. According to the latest available data, Bersani’s coalition should gain around 120 senators, a few more than Silvio Berlusconi’s center-right coalition and less than the absolute majority in the Upper House: definitely not enough to form a stable government.

Berlusconi’s coalition has gained just 500,000 votes less out of more than 40 million voters overall. But the most popular party, as of this writing, is a newcomer: comedian Beppe Grillo’s Movimento 5 Stelle (5-Star Movement), which had been participating in local elections but made its national debut in this election. Disdainfully labeled by its rivals as an “anti-politics” movement, Grillo’s faction has been denouncing the incompetence and corruption of the major parties for years.

Former Prime Minister Mario Monti’s Scelta Civica (Civic Choice) coalition has won less votes than expected and it won’t be able to play as the minority stakeholder with the golden share in any future government. Extreme left and extreme right parties have not overcome the 4% threshold and will not be represented in the coming Parliament.

The only way out of the gridlock would be some sort of unity government like the one Italy has had for the last 15 months. Back then, we just thought it was an emergency solution. Today it looks like the most viable option, but there’s a problem: who is going to be part of this new unity government?

The three main parties or coalitions have very different—if not completely incongruous—agendas.

For Grillo, to join any other party in a government would be suicidal: his movement has triumphed by bashing the “old politics”, and looking for a compromise with representatives of the old politics would definitely smack of treason to the voters. Besides, 2013 is going to be another recession year for Italy’s economy: being at the opposition will all but increase the chances for better results in the following elections. The 5-Star movement may support the other parties on specific bills, but most likely it won’t go as far as entering a coalition government.

That leaves Berlusconi and Bersani’s coalitions. Some say there is no less than an anthropological divide between their respective constituencies, as the first is fond of an entrepreneur who has been accused of mafia connections and the second is loyal to a former Communist Party member. While that may be too much, it is indeed true that their coalitions have different positions on every issue: from the tax cuts to the labor market reform, from Italy’s role in Europe to the limits of the judiciary. For both coalitions, a unity government with the other one is going to be a tough sell.

The only way to make such a grand coalition acceptable to the constituents would be to promise that this unity government would step aside right after a new and efficient electoral law has been approved. New elections should follow.

The upcoming Italian Parliament would be short-lived, but its brief life could be marked by another important accomplishment: In April, together with local representatives, it will elect the new president of the republic. Formally, presidential powers are mostly symbolic, but he or she can use some moral suasion if the parties are unable or unwilling to cooperate. As this person also symbolically represents the country internationally, his or her political value should not be underestimated.

The elections have not yielded a clear result, but in the past both the financial markets and the international partners of the country have forced one: they don’t like uncertainty. Italy will need to work its way out of its political impasse, and will have to do it fast.