Just when it’s needed most, America’s love affair with cereal is coming to an end.

Despite its iconic status in the US, cereal consumption has been falling for the past 10 years, and the trend is expected to continue. In 2005, Americans ate approximately 155 million tons of cereal. By 2015, that had dropped to 134.5 million tons, according to data from Euromonitor.

Cereal companies’ bottom line has been buoyed by higher prices and a shift toward premium brands and products like high-end granola, Jared Koertner, a packaged food analyst at Euromonitor, told Quartz. Sales of new breakfast staples, like yogurt and snack bars, are on the rise as shoppers look for on-the-go options in favor of the kind that require a seat. Ten years ago the cereal market was more than twice that of yogurt or snack bars, but that gap has shrunk considerably. Yogurt sales in the US were up to $8.38 billion in 2015, compared to cereal’s $9.32 billion.

Fast food chains are getting in on the breakfast bonanza, too. Taco Bell has made it a central part of its advertising campaign, following the likes of McDonald’s, Subway, Burger King and a handful of other chains that once relied almost entirely on lunch and dinner. Morning meal sales at restaurants were up 21% in 2014 compared to 2013, according to market research firm NPD Group.

But by skipping the bowl of cereal, Americans are missing out on its original virtue: fiber. Formulated at the turn of the 19th century, cereal was first made to deliver to Americans’ their daily dose of fiber, an important, but oft-ignored, nutrient. The government recommends eating 20 to 35 grams of fiber each day, but a September 2014 USDA review found Americans were eating, on average, only 16 grams each day. The 2010 Dietary Guidelines said that intake levels “are low enough to be of public health concern for both adults and children.” While consuming fruits, vegetables, legumes and whole grains could make up for the shortfall, Americans aren’t doing it.

But the fix is easy: Eating high fiber cereals have been linked to lower risks of many of the diseases that Americans suffer from so disproportionately, including heart disease and Type 2 diabetes. While many people now associate cereal with the high sugar concoctions sold for kids, that is a far cry from its original—and brilliant—iteration.

Cereal’s first incarnation: medicine

Although cereal aisles are now lined with brightly colored boxes, covered in cartoons, and misleading health claims, ready-to-eat cereal was initially an invention of health.

In the 19th century, wealthy Americans broke their fast on a variety of animal products, including today’s favorites like eggs and bacons, but also oysters, veal and wild pigeons. A vegetarian surgeon and his wife wanted to serve the patients at their Battle Creek, Michigan sanitarium something healthier, Melanie Warner explained in her 2013 book, Pandora’s Lunchbox: How Processed Food Took Over the American Diet. The couple, Dr. John Harvey Kellogg and his wife Ella, began experimenting with oatmeal and whole wheat porridge, trying to create a low-fat, high-fiber breakfast that visitors could take with them when they left.

Flaked cereal was born out of an accidental discovery. After Ella forgot to drain the water from a batch of boiled wheat kernels, Kellogg ran the resulting mush through a roller, creating a flattened flake, which he then baked in a pan. In 1897, Kellogg established the Sanitas Food Company, a mail-order cereal company for former patients of the sanitarium who wanted to adhere to Kellogg’s “biologic” grain-based, vegetarian diet.

Eventually, Kellogg’s younger brother, Will Keith Kellogg, joined him in the business and while the older Kellogg was in Europe, added sugar to the recipe. John Harvey was livid, but the sugar stayed—customers loved it. The brothers never reconciled, and eventually Will Keith bought out his brother’s share. He went on to found what we now know as the Kellogg Company, selling billions of dollars of sugar cereal—and the healthy kind—each year.

Cereal’s secret sauce

Earlier this year, researchers at the Harvard School of Public Health published a study linking high cereal consumption with a lowered risk of death, and specifically death from cardiovascular disease, Type 2 diabetes, and certain cancers.

Using data from the National Institutes of Health-AARP Diet and Health Study, the analysis included 367,442 AARP members, ages 50 to 71, none of whom reported at the outset that they had cancer, heart disease, stroke, diabetes or end-stage renal disease. The responses to the questionnaires were recorded in October 1995 and December 1997, and the dataset includes information on both date and cause of death.

Even without adjusting for confounding factors, the researchers found that high consumption of ready-to-eat cold cereal was inversely correlated with being overweight or obese, smoking, and eating red meat, and associated with higher levels of physical activity, reflecting that cereal is often part of a healthy lifestyle. But once they adjusted for confounding factors, including age, smoking status, education, race, marital status, physical activity and the rest of the participants’ diet, the results were even more telling: The people who ate the most cereal had a 15% lower risk of all-cause mortality, a 10% lower risk of dying of cancer, and a 30% lower risk for Type 2 diabetes.

Cereal’s special sauce is likely its fiber, the researchers write. “Within ready-to-eat cereal consumers,” the analysis found, “total fiber intake was significantly related to reduced risk of total mortality.” It was also associated with lower risk of cancers and respiratory disease.

“It’s not very surprising based on previous findings,” Lu Qi, an adjunct professor in the Department of Nutrition at the Harvard School of Public Health, told Quartz. Those findings include that eating cereal for breakfast is associated with better cardiometabolic health in young adults, lower body mass index for minority children, and lower weights for adult men.

Fiber works in a number of ways to help protect health. Soluble fiber, the kind that dissolves in water, is great for lowering cholesterol because it grabs onto cholesterol and its precursors “and drags them out of the body before they get into circulation,” as the Harvard School of Public Health explains. Insoluble fiber, which does not dissolve in water, performs another important function: Because it isn’t digested in the gut, it acts instead as a bulking agent, which reduces constipation. Both soluble and insoluble fiber are important, and most bowls of oat-, bran- or wheat- based cereal topped in fruit will have both.

A simple way to lose weight

Eating more fiber has also been identified as the simplest dietary change a person can make to lose weight. A study published in February in the Annals of Internal Medicine identified an increase in fiber as a single change that can help people lose weight, as opposed to an overall shift toward healthier foods.

Two groups of dieters participated, both with metabolic disorder: one ate an American Heart Association-approved diet, focusing on eating more fruits and vegetables and less salt, sugar and fat; the other only had to eat 30 grams of fiber a day, as part of their regular diet. While the AHA dieters lost more weight over a 12-month period, dropping an average of 5.9 lbs., the fiber dieters also lost a significant amount of weight, at an average of 4.6 lbs. per participant. ”A simplified approach to weight reduction emphasizing only increased fiber intake,” the researchers concluded, “may be a reasonable alternative for persons with difficulty adhering to more complicated diet regimens.”

Under Armour, whose MyFitnessPal app allows users to track their eating and weight loss, has seen a similar trend. Their approximately 700,000 “successful users”—those within 5 lbs. of their weight goal—ate 29% more fiber than the rest of the users and 17% more cereal.

Fiber has long been known to reduce appetite, and a 2013 study published in Nature Communications found that acetate, a molecule released when fiber is digested, may be playing an important role in the process. The acetate goes from the gut to the brain, where it signals the feeling of satiety. The researchers fed the dietary fiber to rats on a high-fat diet. They found that those given the fiber ate less, and gained fewer pounds, than those not receiving the fiber. The fiber-fed rats also had increased amounts of acetate in their guts.

But just because a cereal says it’s good for weight loss doesn’t mean it’s high in fiber (or good for weight loss, for that matter). Koertner specifically pointed to Special K as one of the struggling brands promoting itself as diet food and failing to convince consumers. Its fiber content: 0 grams.

Not all cereal is created equally

Qi’s team wasn’t able to track which cereals its participants were eating, but choosing wisely is half the battle. “Not all cereals are created equally,” says Jayne Hurley, a senior nutritionist at the Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI), adding that it’s important to know the source of the fiber, as well as its quantity when choosing. CSPI recommends looking for cereals made with whole grains, less than 250 calories per cup, at least 3-6 grams of fiber, few—if any—added sugars, and low sodium levels.

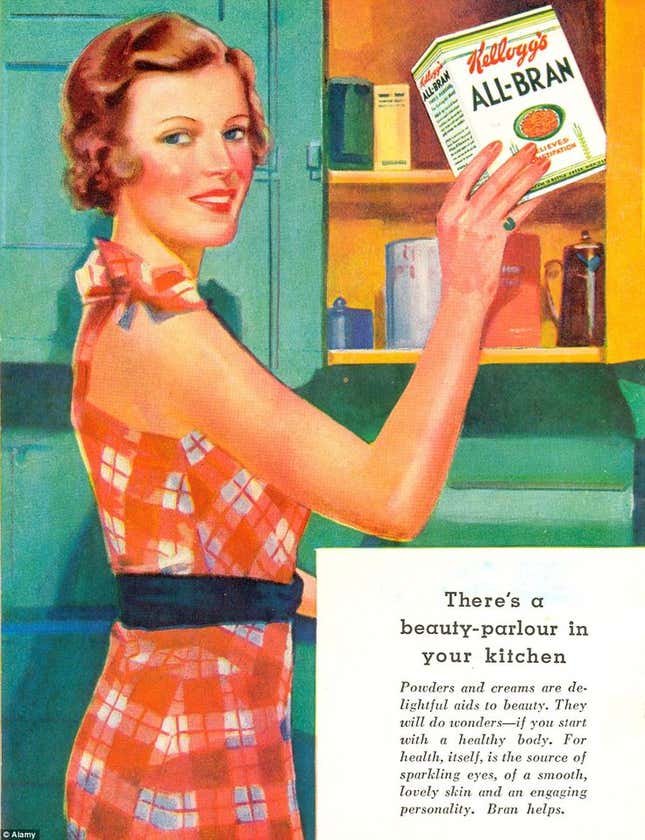

“Get fiber that’s real fiber like bran, not processed fiber like chicory root fiber, inulin, oat fiber or oat hull fiber, or soluble corn fiber,” Hurley says. But a little bit of sugar is okay, too. Even Kellogg’s All Bran, which Hurley calls “one of the best cereals you can buy,” has 6 grams of sugar. Tinh Le, a registered dietician at MyFitnessPal, says to aim for less than 8 grams of sugar.

As for the yogurt craze, Hurley says she’s a big fan of the popular Greek kind, but when it comes to those breakfast snack bars, she tells Quartz, “I couldn’t find a single one to recommend.”