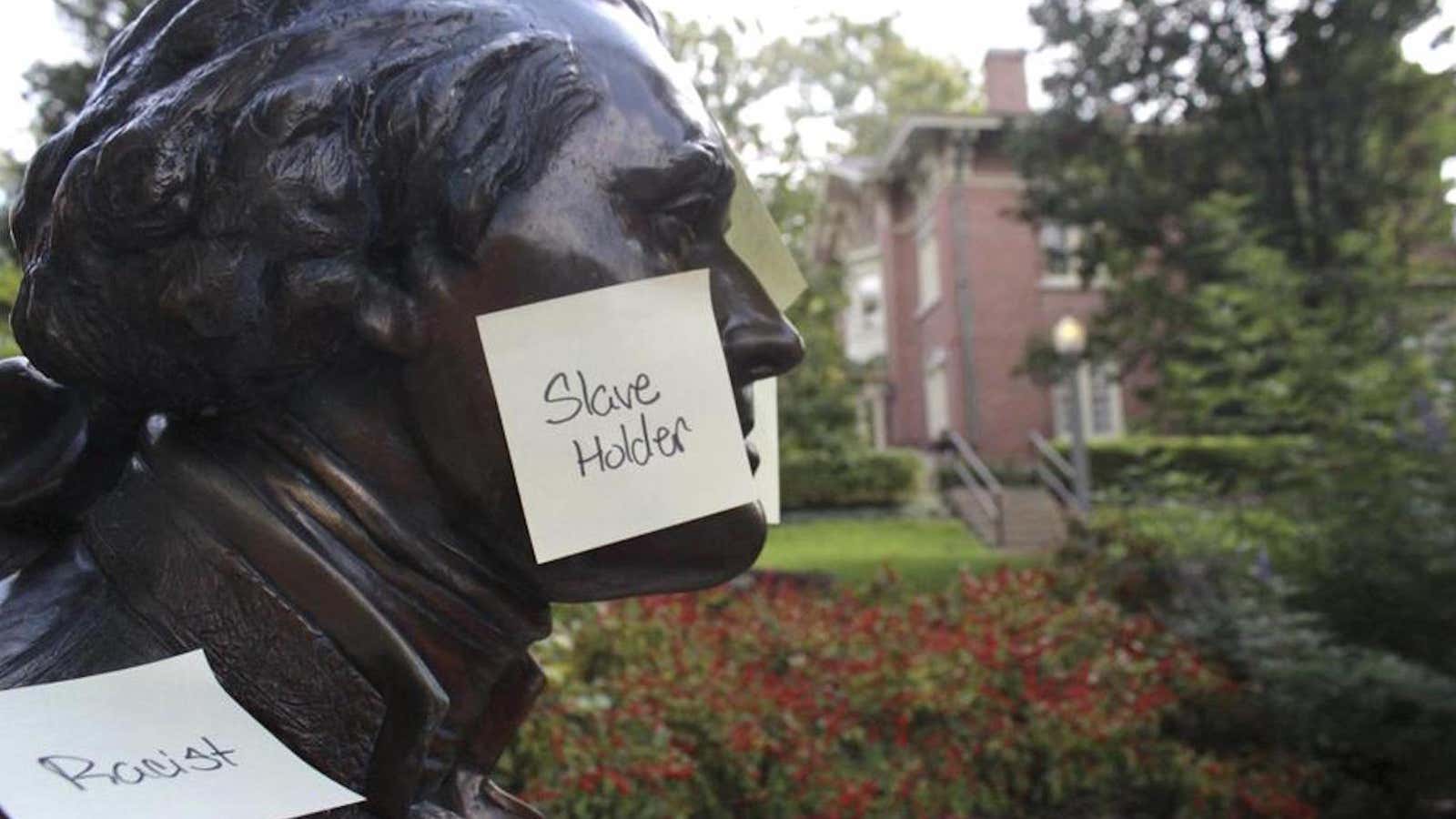

Students at Princeton, the University of Oregon, the University of Maryland and more have demanded the names of racists and slaveholders be wiped from campus buildings and programs. Georgetown recently renamed two buildings after students there made similar demands. And Princeton and Harvard have retired the antebellum-inflected title of “master,” heretofore used to refer to heads of colleges on campus. Yale students have asked for the same.

The zeal with which students have called for these changes—and their surprising success—is reminiscent of the debate over the Confederate flag in the wake of the Charleston shootings this summer. Initial calls to ban the flag were met with resistance, but were quickly overcome by a swelling tide of voices both online and in real life demanding the flag be outlawed and removed.

Working in a newsroom, one registers these moments acutely. I remember feeling a shift in the world order. Suddenly, the opinions slung around on the internet were showing up in courthouses. One day, a senator spoke against the flag; the next day, a mayor defended it. Arguments left the realm of Twitter and opinion pieces, and manifested themselves in legislation, in a way that mattered.

For a few weeks, America was actively invested in examining and improving its symbolism.

As a recent graduate of an elite university, I can attest that this is what it’s like to be a student on a liberal arts campus almost all of the time. Many of the students at schools where protesters are now calling for equality spend the majority of every day teasing ideas out of texts assigned by professors who have devoted their lives to chasing abstractions. Academia is built on the expectation—the hope—that by applying these abstractions to reality, mankind can evolve. By generating a conception of what our world could be, we believe, we might defy the status quo, buck the momentum of centuries of flawed civilization and move in a different direction.

The rhetoric of student protesters across the country this fall has taken on the life or death tenor befitting such an endeavor. It is the same tone that characterized the fight to ban the Confederate flag this summer, only this time it has resulted in the protesters being characterized as hyperbolic, naïve “social justice warriors.” In a column for New York Magazine, Jonathan Chait warned against the threat student protesters’ “hypersensitivity” poses to “free speech,” and Conor Friedersdorf has condemned students’ preoccupation with ideology in the Atlantic.

In the case of the debate over the Confederate flag, no one could say its dramatic tone was misplaced: nine deaths in Charleston preceded it. But in the case of the events at Yale, for example, it was a seemingly well-intentioned letter to a college of students that precipitated the eruption of what has turned into a bitter argument over cultural sensitivity and exclusion. This has led to critics labeling the students as immature. For those unfamiliar with what happened at Yale in October, Freidersdorf’s article offers a nice recap. He rightly characterizes the letter written by Erika Christakis (who has decided not to teach next year) as “level-headed,” but misunderstands the students who reacted to it.

“The focus belongs on the flawed ideas that they’ve absorbed,” he writes, framing Yale as responsible for turning these kids into narrow-minded “bullies.” He warns that Yale and other elite schools are doing their students a disfavor by telling them what costumes are not appropriate to wear for Halloween, which he sees as a form of coddling acculturation.

This is the same reasoning at the root of a larger argument against politically correct culture in American academia. It argues that by sheltering students from “dissenting” views (lately, code for racism), universities are inhibiting students from developing critical thinking skills, making them into “illiberal” ideologues. A line from a recent open letter to Cornell University illustrates this anxiety to a tee: “We are now raising a generation of coddled, narcissistic, self-absorbed, thin-skinned young people, permanent ‘victims,’ who will be ill-equipped to function effectively in the real world outside the shelter of the academy,” Cornell alum Lee Bender wrote. The argument itself is misleading. It reduces the students to selfish automatons, devoid of perspective and the ability to think freely, when there is no proof that these students are any less prepared to go out into the world and thrive as they fight for what they believe in. Additionally, in its paternalistic concern, the argument dismisses the symbolic statement students are making by refusing “free speech” as a justification for disrespectful behavior and inequality.

Trigger warnings, which arose on feminist blogs in the 2000s as a way to forewarn readers of potentially upsetting content, have been the target of this argument in the past. Like faculty memos to students, in reality, the efficacy of trigger warnings is likely pretty low. Psychological triggers are often specific and unpredictable, and are therefore unavoidable. The practical argument against them, that by shielding students you are doing them a disservice, is obsolete in light of this fact. But trigger warnings are not. They serve an important purpose “as a linguistic in-group designation,” one feminist blog explains. A trigger warning “not only indicates that the content that follows is about rape, but signals that the narrator is asserting her narrative into a feminist space.” This operates as a signal of respect for others in the space and an acknowledgement of the effects and reality of trauma. Which is to say, more than anything, they are symbolic.

Likewise, the email from Yale faculty asking students not to wear offensive costumes is a symbolic declaration of minority students’ right to live in a community where they are not demeaned by other students’ decisions to wear headdresses or blackface, as much as it is an attempt to control students’ choices. Christakis’ letter, in addressing the practical effects of the email, missed this symbolism and undercut that declaration.

I do not believe that Christakis or Freidersdorf is ill intentioned, as those who stand in active opposition to student demands for equality may be. Rather, I believe they missed the ideological connection between the faculty’s email and the world these Yale students are fighting for. Like banning the Confederate flag, wiping racists’ names off of campus buildings and asking students to be respectful on Halloween are gestures that take on importance in the realm of symbolism that they lack in the realm of practicality in which Christakis, Freidersdorf, Bender and other critics have mistakenly judged them.

Finally, Friedersdorf notes that “what happens at Yale does not stay there,” referencing the fact that Yale students go on to become world leaders and guide research in their fields. That’s why it’s important, contrary to the prescription that Yale stop coddling these students, that Yale support their ability to imagine the world as it should be by encouraging them to be socially responsible in addition to thinking freely.

Outside the Ivory Tower, it took a brutal shooting to generate the momentum necessary to ban the Confederate flag. Perhaps today’s politically correct students—the future leaders of America—can proactively imagine a better world of tomorrow.