Spain is on the brink of a general election that looks set to change its political system for good. How come?

To understand what’s going on, we need to look back at the protests that filled the squares of Spain in May 2011 and triggered one of the most dynamic and sustained episodes of citizen mobilization the country has ever seen.

Initially youth-led but ultimately galvanising citizens of all ages, the protesters demanded “Real Democracy Now!”, calling for an end to a political system that alternated power between two parties that both served the interests of political and economic elites rather than the Spanish people. Given the acute effects of the economic crisis and ensuing austerity policies, these demands were met with widespread support from an astonishing 80% of the population one year after the May 2011 protests.

Although the so-called 15-M was at first a staunchly anti-partisan pro-democracy movement, everything changed when a party “project” was created that aimed to combine elements of participatory social movements with an electoral challenge to the parties in power. Although not convincing all 15-M participants, many decided to put their energies into the new party – Podemos. Just four months after forming in 2014, it managed to win 1.2m votes and five seats in the European Parliament, heralding a radical shift in Spain’s political landscape.

These results spurred the setup of an array of municipal platforms that managed to take control of some of Spain’s major cities, including Madrid, Barcelona and, in a historic upset in May 2015, Valencia.

The support of these coalitions for Podemos in the national elections (where Podemos is presenting on coalition lists in some regions, notably Catalonia), and especially Barcelona Mayor Ada Colau, has also been important.

Podemos’s ability to capture political ground rested on two key strategies: defining itself as a party of ordinary citizens that was neither left nor right, and attacking the political establishment as representing a corrupt “caste” that refused to listen to the demands and needs of ordinary citizens.

But the blows Podemos dealt to the established parties’ credibility and legitimacy presented an opportunity for other “new” political actors and just such a force has emerged in the form of upstart Ciudadanos.

Competing upstarts

Following a spectacular entrance onto the political scene, which saw Podemos shoot to the number one position in the polls in January 2015, it has been somewhat upstaged by a “new” challenger, the right-wing party Ciudadanos.

Despite not really being new – it has existed in Catalonia for more than ten years – the party, with its young leader Albert Rivera, has managed to sell itself as a more centrist alternative to Podemos. It has made anti-corruption a key part of its rhetoric, and even adopted a slight modification of Podemos’ campaign slogan in the European parliamentary elections for its campaign slogan in the general elections: “¿Cuándo fue la última vez que votaste con ilusión?” (when was the last time you voted with hope/excitement?) became Ciudadanos’ slogan “Vota con ilusión” (vote with hope/excitement).

But despite being perceived as fresh new alternatives that hope to capture the political centre, the two parties remain profoundly different.

Ciudadanos is a socially and fiscally conservative party with an ideology close to the ruling Popular Party, although it uses primaries for candidate selection and has written anti-corruption measures and restrictions on party donations into its “commitment to democratic regeneration”. Podemos, on the other hand, is a socially and fiscally progressive party, close to the main opposition Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE) on many issues, with decentralised and participatory mechanisms for internal party decision-making, solely crowdfunded finances, and a general commitment to transparency.

Most citizens see Ciudadanos as a centrist party that scores well across a wide range of social and economic issues and Podemos as a left-wing party that scores very high in social issues but lower on economic issues. The support they have garnered has changed the profile of both the PSOE and the Popular Party (PP), who are now moving further left and right respectively.

Whereas Podemos is taking votes from the PSOE, Ciudadanos has managed to take votes from both the PP and the PSOE. Both receive support from young voters.

Generational split

The polls show a marked generational split, with Podemos as the favourite party among voters younger than 35 and especially with first time voters, and Ciudadanos occupying the top spot with voters aged between 35 and 44.

PSOE and PP supporters, on the other hand, are significantly older: the PP is in fourth place among voters under the age of 45, but shoots up to first among voters over 65, from whom it has 53% of its support.

This generational split will have a lasting significance well be beyond these elections. The PP depends on a base of voters much older than the rest of the electorate, while Podemos and Ciudadanos are getting a lot of support from first-time voters. That means they’re probably here to stay, since Spanish voters seem to dependably stick with the party they choose the first time they vote.

What the polls say

All the major polls indicate a win for the PP, but by a very small margin, with 41% of voters still undecided as of December 14. The range offered by the eight major polls indicate 103-128 seats for the PP, 76-94 seats for the PSOE, 52-72 seats for Ciudadanos, and 45-63 seats for Podemos.

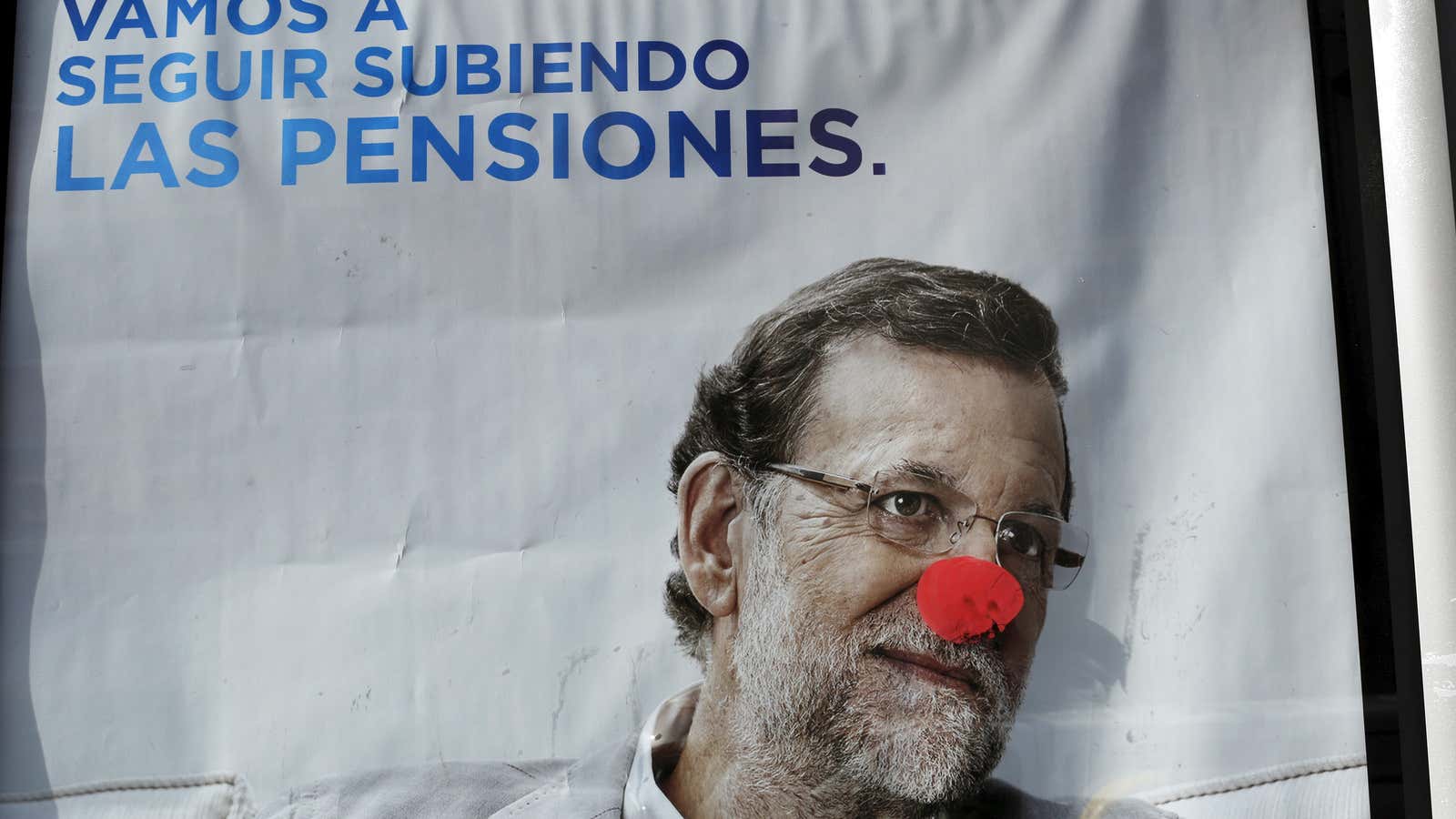

The last polls that can legally be published came out on the same day as a televised debate between current president Mariano Rajoy (PP) and PSOE candidate Pedro Sánchez. Post–debate feeling seemed to indicate “win” for the PSOE and a “loss” for the PP, but in the absence of hard data, it is impossible to say what effect the debate will have on the elections.

Whatever the outcome, it’s clear that the era of two-party rule is over, and that no party can expect to win an absolute majority. Forming a government will probably require pacts between more than two parties – and according to the CIS pre-electoral survey, 58.2% of Spanish voters would be happy with that.