A pair of Australian sea snakes just scored a couple points against the Sixth Extinction. Scientists had given them up for extinct after the two species—the short nose and the leaf scaled sea snakes—disappeared from their homes on the Timor Sea’s tropical reefs more than a decade ago.

Strangely, though, in the last few years, dead specimens of both species had washed ashore off the coast of Western Australia. Then, in 2013, a park ranger in the area spied two unfamiliar maize-colored sea snakes canoodling in the waters off western Australia, snapped a photo, and sent it to a biologist at James Cook University for identification. It turns out, it was the short nose sea snake—living 1,700 kilometers (1,056 miles) south of their only known habitat.

“We were blown away. These potentially extinct snakes were there in plain sight, living on one of Australia’s natural icons, Ningaloo Reef,” said Blanche D’Anastasi, a scientist at JCU’s center for coral reef studies, and lead author of a study focused on the sea snakes. “What is even more exciting is that they were courting, suggesting that they are members of a breeding population.”

On top of that good news, the researchers went on to discover a population of the leaf scaled sea snake in the seagrass beds of Shark Bay, further along the coast.

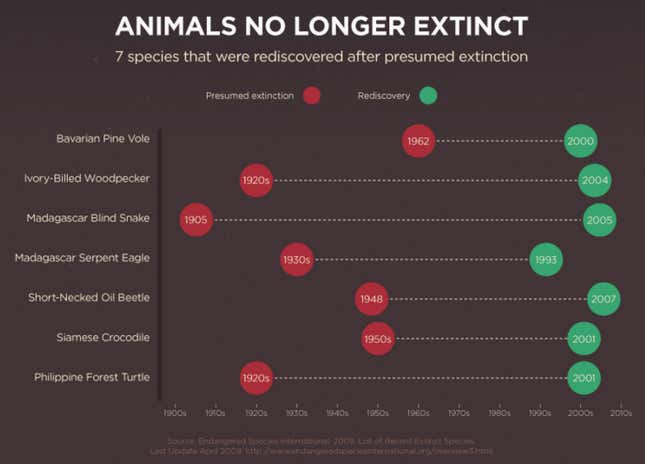

This sort of “rediscovery” of species given up for extinct happens more often than you might think. Every year, a a few species are rediscovered. And some species are labelled extinct, erroneously, for far longer than the two Australian sea snakes. In March, for instance, a bird called Jerdon’s Babbler was found in Myanmar; the last sighting was 1941. This isn’t uncommon, as you can see from this chart from the Discovery Channel’s recent documentary, Racing Extinction:

That this happens reflects the limits of our understanding of animals and their habitats. For instance, in the case of the sea snakes, scientists hadn’t realized the two species could live in habitats so vastly different from the Timor Sea’s coral reefs. Both species’ unexpected adaptability to new habitats suggests that they might not even face imminent risk of extinction, say D’Anastasi and her colleagues in a just-published paper confirming the discovery (paywall).

Obviously, this ignorance sometimes makes us overly pessimistic. That said, there’s limited room for optimism. As the study’s authors highlight, we still don’t know why the two sea snake species went extinct in the Timor Sea. And that lack of knowledge, say the researchers, makes it hard to know how to protect the two rediscovered sea snake species in their Australian habitat.