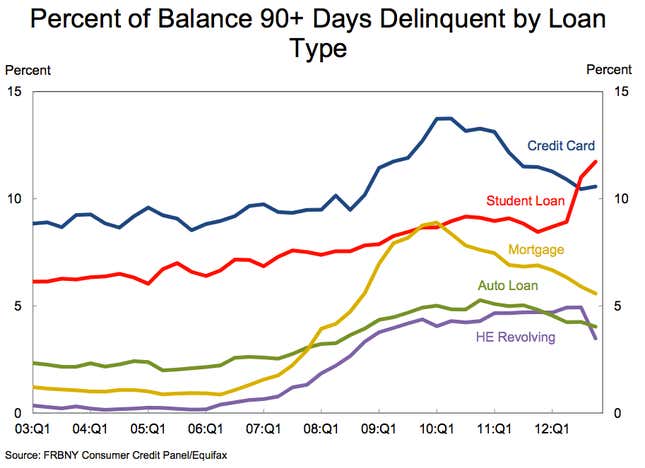

The above graph comes from this week’s New York Federal Reserve’s quarterly report on American credit, which offered mostly good news: Overall household debt remains below the 2008 peak, and delinquency rates broadly improved. But there’s one asset class where delinquency rates and borrowing are both increasing: student loans for higher education. These are also the only debt that continued rising through the recession, tripling between 2004 and 2012.

There are now more people in the US borrowing money to pay for college than to pay for cars or credit cards. What’s more worrisome? Some 17% of the borrowers are delinquent on their loans, up from 10% in 2004. And that’s not even the real delinquency rate, since it’s the percentage among all borrowers, including those who are still in school and thus aren’t yet repaying their debt. If you remove those from the total, the delinquency rate rises to 30%.

The reasons are clear: Higher education gives students a greater chance of prosperity, making it a sought-after commodity. But the cost of it has far outstripped inflation. People increasingly need a post-graduate degree to be competitive, so they are spending more time in school and out of the workplace. And the laws around student debt are tighter than other kinds of consumer credit, making it difficult to discharge the obligation in bankruptcy.

But the consequences are only starting to become apparent. One is that people burdened with student debt spend less on other things, can’t obtain credit for other purposes, including mortgages, and are often delinquent on other debts they incur. Another is that the more debt you need to take on to get an education, the more the system becomes unfairly rigged in favor of the better-off. But also consider this report from the Wall Street Journal:

[T]he largest U.S. student lender known as Sallie Mae, on Wednesday sold $1.1 billion of asset-backed securities supported by private student loans, drawing nearly 15 times the required demand to sell out the riskiest slice, people familiar with the deal said. It was the first time since before the financial crisis that Sallie Mae has opted to sell the riskier portion of an offering, having retained it in previous deals.

While the loans in this deal may be high-quality, the demand for the high-risk slice suggests that investors seeking higher yields are interested in securitized student loans. Which means that they are seeking yields in vehicles backed by the only consumer-credit category where the failure to pay on time is rising.

Ultimately, this is a problem driven by the cost of higher education, and some combination of competition, government regulation, technological disruption and a re-thinking of what people really want out of the experience. But while that’s all being figured out, President Barack Obama is trying to force colleges to be more transparent about how their graduates are employed, providing more information to borrowers. And Congress may take up a measure to allow student loan debt to be discharged in bankruptcy. That would at least help alleviate the pressure on those whose expensive degrees don’t get them the jobs they hoped for.