This post has been corrected.

On Jan. 12, 2015, his last day as Illinois governor, Pat Quinn signed legislation to regulate Uber and Lyft across the state.

The particulars of the bill were boring—they laid out how ride-hailing services would insure drivers, conduct background checks, and deal with alcohol violations—but its passage was anything but. The new law permanently ended the bitter political fight Uber had waged in Illinois over the last year. Earlier drafts had considered limits on Uber’s pricing, its pickups, its driver hours; Uber lampooned them as harming “consumer choice, safety, economic development.” The final bill that Quinn signed contained no such restrictions. It at once protected Uber and legitimized it.

Uber heralded the legislation as “groundbreaking.” It called for “similar progress” across the country.

The year 2015 was filled with milestones for Uber. The company now operates in well over 300 cities. Its valuation soared above $60 billion. New products like Uber Eats. The millionth driver. A big push on UberPool. A multibillion-dollar bet on China.

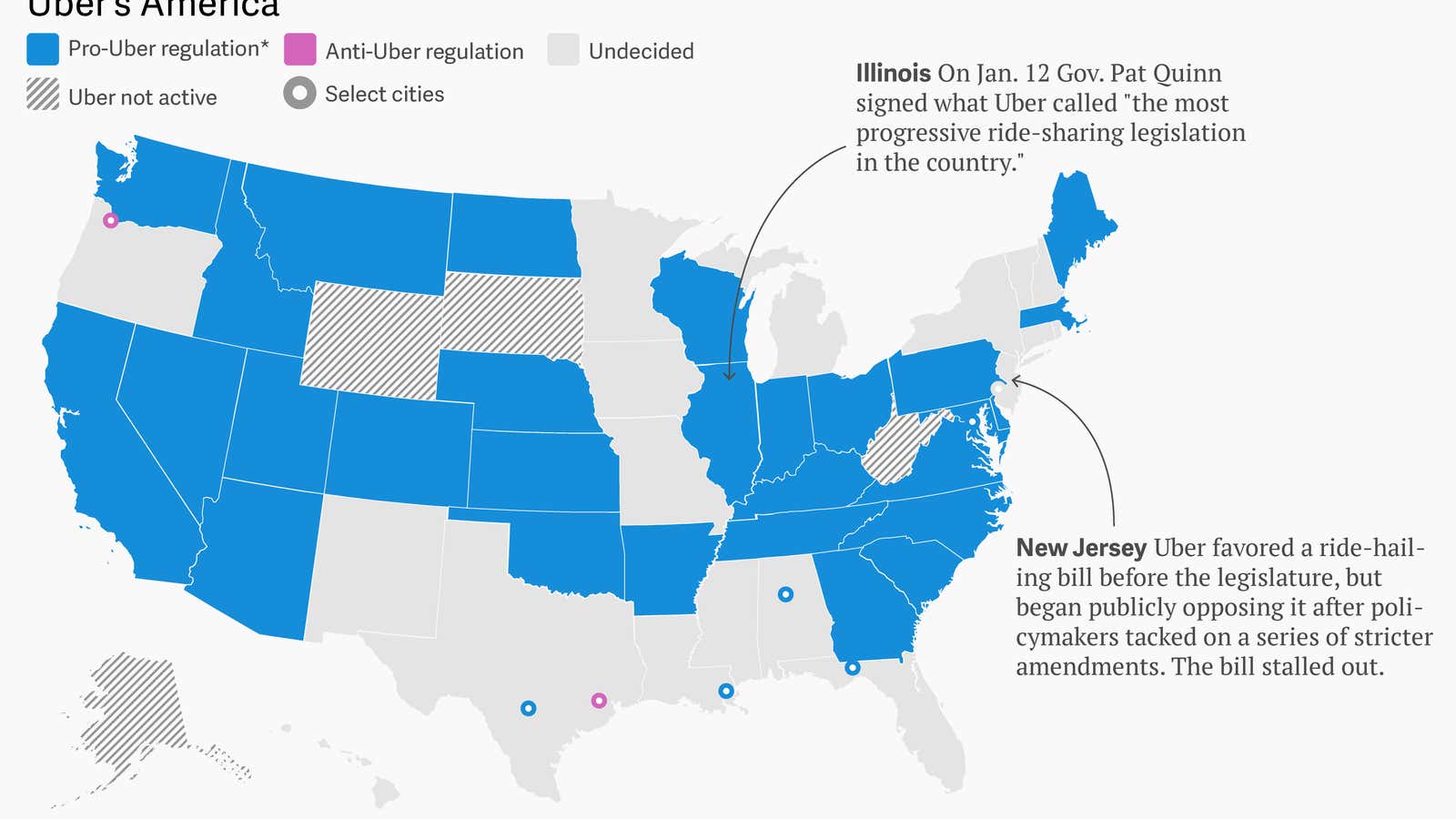

But perhaps no accomplishment was so significant as Uber’s march across America’s regulatory landscape. What started in Illinois had expanded to include more than half of the country by the end of 2015. In city after city, state after state, Uber beat out entrenched interests, brokered deals, and pushed policymakers to get its preferred laws on the books. It was a stunning and sweeping political coup that’s gone almost unnoticed.

To lead its campaign—a term Uber itself has used—the company has assembled a formidable team. The most prominent member of its policy arm, former Obama campaign manager David Plouffe, joined in August 2014. This past spring, Uber brought on Rachel Whetstone, Google’s seasoned policy and communications chief, and shifted Plouffe to an advisory role. Also on Uber’s policy and PR roster: Jill Hazelbaker, formerly of Snapchat, Google, and Sen. John McCain’s presidential campaign; until recently, Matt McKenna, longtime Clinton Foundation spokesman, and Corey Owens, a former public policy manager at Facebook.

The combined power of this group and Uber’s slick technology has made it the standard-bearer of a new kind of grassroots lobbying. In its ride-hailing app, Uber has what traditional campaign managers can only dream of: an instant and intimate connection to a vast user base. When New York City mayor Bill de Blasio attempted to stymie the company’s growth last summer, Uber deployed DE BLASIO mode. A proposal from city council member Ann Kitchen in Austin, Texas, was derided with KITCHEN’S UBER. In other cities, Uber has published the names and contact information of local officials through its app and online, encouraging residents to get in touch about rules it deems “restrictive” and “onerous.”

Such targeted attacks might be brash, but they’re also effective. In 2015, 22 states passed comprehensive ride-hailing legislation. Some did so painlessly; others succumbed to Uber’s lobbying. Only a handful of cities have hung onto regulations such as finger-printed background checks that clash with Uber’s preferences.

“Nearly every time we try to set up shop in a new city, there’s a powerful industry with powerful allies who try to stop progress,” Uber CEO Travis Kalanick remarked on the company’s five-year anniversary in June. “The only reason they haven’t succeeded is because of you. It’s because there’s always a handful of Uber riders and drivers who decide to stand up and speak out and petition City Hall. And then they’re joined by a few more. And then a few more. And pretty soon, an entire community of people is fighting for a new way of doing things that makes their lives a little easier.”

Regulatory battles are one of the few arenas in which Uber and its chief US rival Lyft have found themselves aligned. Lyft, which has taken a softer political tact and mostly avoided public confrontations with cities, has nonetheless benefited from Uber’s campaigns. “We look back on 2015 as really the tipping point in the creation of a regulatory framework across the country,” Joseph Okpaku, Lyft’s recently appointed VP of government relations, told Quartz.

Counting operating agreements in a handful of states, more than half the country is done. But nearly half is left. Uber-sponsored bills fizzled last year from Hawaii to Connecticut. Some legislation simply stalled out; other proposals, like the one Uber originally supported in New Jersey, died after legislators tacked on stricter provisions about background checks and insurance and the company pivoted to oppose it.

But a new year and new legislative sessions will bring fresh attempts. Any time another regulator comes on board, Uber’s leverage over the holdouts increases. No state, no politician wants to appear anti-innovation, after all, and making dissenters seem passé is an Uber specialty.

So why risk it? Better to be seen as facilitating progress than obstructing it, to codify for constituents a service that they’ve vocally demanded. In Uber’s America, what matters is that “groundbreaking” legislation can be spun as a win for everyone.

Correction (Jan. 22): An earlier version of this article misstated that Matt McKenna is on Uber’s policy and communications team. He recently left Uber. The original map in this article also incorrectly showed that the latest regulations in New Orleans are anti-Uber, when in fact they are pro. The map has been fixed.