Meet the charming, kooky predecessors to the modern keyboard

In this digital age, it’s worth remembering that the Latin root of “digital” refers to our fingers, perhaps the only part of our bodies now working harder and faster than ever. And in the English-speaking world, our fingers are slaves to QWERTY.

In this digital age, it’s worth remembering that the Latin root of “digital” refers to our fingers, perhaps the only part of our bodies now working harder and faster than ever. And in the English-speaking world, our fingers are slaves to QWERTY.

It’s a letter configuration system that first debuted on an ancient predecessor to today’s touchscreen: the typewriter. The QWERTY keyboard appeared on the first commercially successful typewriter, the Sholes and Glidden of 1874 made by E. Remington and Sons. QWERTY happened to be the first six letters on the top alphabet row, and by dint of the typewriter’s popularity, became the organizing principle of keyboards today.

But what if we’d taken another direction? Canadian collector Martin Howard is an archaeologist of our digital era, digging up old fossils and relics in junk stores: typewriters and keys so old they predate your grandparents’ Underwood and Olivetti models. His incredible collection reveals many of the paths not taken, in terms of keyboard design—while today’s key layouts are relatively standardized, 19th century solid-metal typewriters came in all kinds of inventive forms.

Howard’s fascination with antique typewriters began after he spotted a Calligraph 2, in a junk shop. Over the years, he has restored more than 60 models, spending hundreds of hours tinkering, buffing and classifying each one based on his avid research of each model’s history. Howard has revived typewriters with rotary discs and dials, curved keyboards and ornate decorative covers.

Here are a few, whose unusual configurations are worth keeping in mind next time you bemoan finger fatigue or a computer malfunction.

The Ford typewriter is a most impressive machine with its ornate grille and gracefully integrated keyboard. It is the invention of Eugene A Ford, a man with a very distinguished career. Ford worked with Herman Hollerith, director of the United States Census, and founder of the Tabulating Machine Company. Hollerith created the first mechanical, punched card data processing equipment that would revolutionize the collecting and disseminating of information for the US Census.

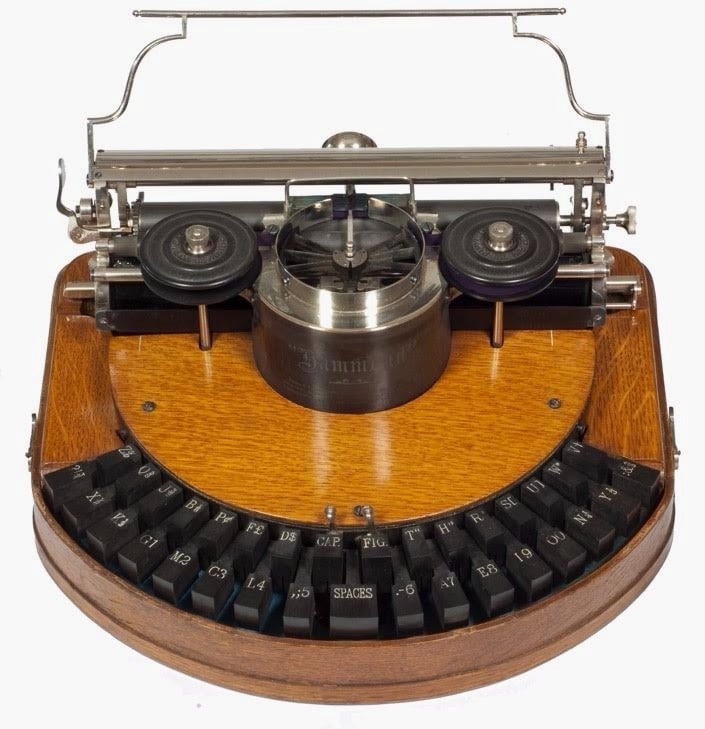

James Hammond is one of the great typewriter pioneers, beginning work on his remarkable machine in the late 1870s. His typewriter has a truly brilliant mechanical design and great looks too. Encased in golden oak and with solid ebony keys, it is of the highest quality. This typewriter sold for $100, a common price for a full keyboard typewriter of the day. In comparison, a horse drawn carriage sold for between $40 and $70.

This beautiful little machine was invented by Charles Spiro, a New York watchmaker, mechanical inventor, and lawyer who went on to create other superb typewriters. To operate, the black handle rotates the pointer on the dial to select a character and then is pushed down to print. One end of the pointer is for lower case and the other end is for uppercase characters. It is notable to mention that Mr. Spiro, at age 16, in his father’s watch shop invented the stem setter and winder for watches. Before this invention, watches had separate keys that were inserted into the front or back of the watch for this purpose.

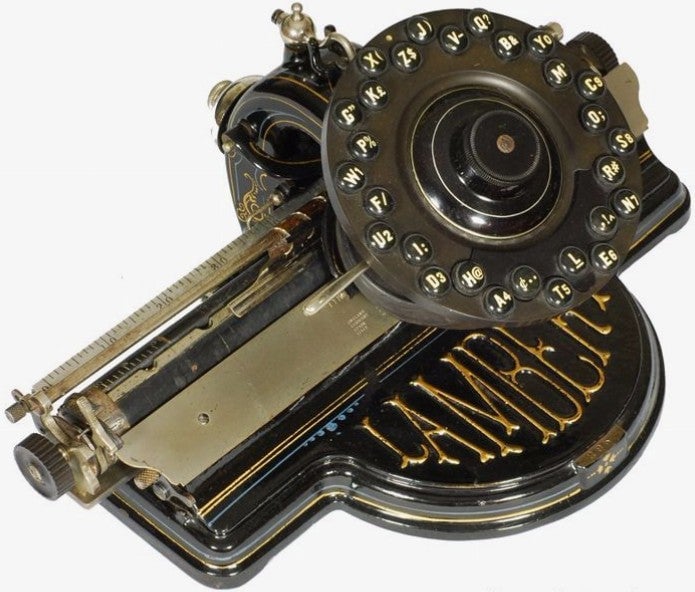

The Lambert is a typewriter with a most unique design. Frank Lambert, a French immigrant, spent seventeen years developing his typewriter. One types by pushing down on one of the character buttons, causing the whole spring loaded disk to tilt down. Underneath just above the typing point is a convex vulcanite disc, with all of the characters molded onto it, that makes contact with the paper.

This was the first typewriter to use a single type-element (no type bars) —well before IBM’s Selectric typewriter of 1961 with its ‘Golf ball’ type-element. Like the Selectric, the Crandall’s cylindrical type-element could easily be changed to type with a different font style.

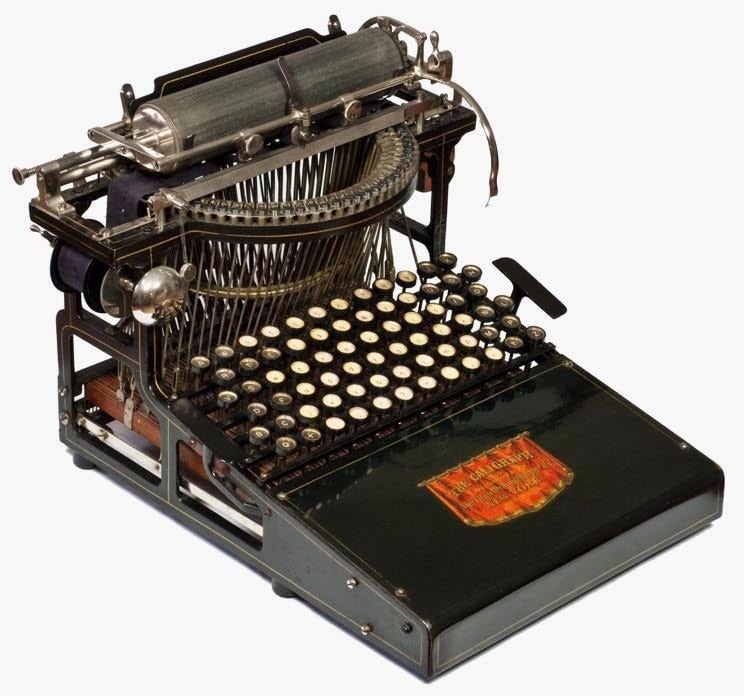

The Caligraph was the first typewriter to be produced with a double keyboard. With no shift key, a double keyboard was needed: black keys for uppercase characters and white keys for lowercase. I am dubious of the following period announcement: “GREATEST SPEED ON RECORD!! T. W. Osborne wrote 179 words in one single minute, and G. A. McBride wrote 129 words in a single minute, Blindfolded, on the Caligraph”

Who still buys these typewriters today? Though most collectors buy vintage typewriters as art objects or “working sculptures,” as Howard puts it, there are still those some who succumb to the romance of using these beautiful but unwieldy writing machines.

“There are people who still enjoy the old fashioned typewriter, with its sounds and permanence, as the characters are immediately inked on paper,” Howard tells Quartz. He has sold them to customers from the US, Europe and Asia. “They feel that there is a fluidity as they smack the characters onto the page, somewhat like a chisel being struck with a hammer sending wood chips flying.”

Today, typewriters are still in use in some police departments in New York City as well as some places around the world where electricity is unreliable. In 2014, the German government resorted to manual typewriters to send messages off the security grid. Others, like the Boston Typewriter Orchestra and similar ensembles have found a way to creatively repurpose these dinosaur business machines, using them as percussive instruments to transform that once-familiar tic-tic-tic noise to music.