This Italian company pioneered innovative startup culture—in the 1930s

Today, Silicon Valley may be the seat of innovative business culture, but the model for this arguably dates back to Italy in 1932, the year Adriano Olivetti took over his father’s typewriter business.

Today, Silicon Valley may be the seat of innovative business culture, but the model for this arguably dates back to Italy in 1932, the year Adriano Olivetti took over his father’s typewriter business.

He put to use a management strategy that wound up deeply influencing business culture worldwide: It’s said that IBM’s mantra, “Good design is good business,” was inspired by a display of Olivetti’s typewriters.

A politician, as well as a chemical engineer and entrepreneur, Olivetti had a philosophical view of entrepreneurship, one that put people and communities at the center of a business. He was a firm believer in the competitive advantage of treating workers fairly and investing in their wellbeing. Andrea Granelli, president of Associazione Archivio Storico Olivetti (Olivetti’s historic archive association), told Quartz “the profits from sales were invested in innovation, expansion, higher salaries, social services.”

Cultura Olivettiana (Olivetti’s culture) has left a strong mark in Italy’s management culture. In its heyday, Olivetti provides an interesting model for technology companies trying to build an innovative culture alongside their product.

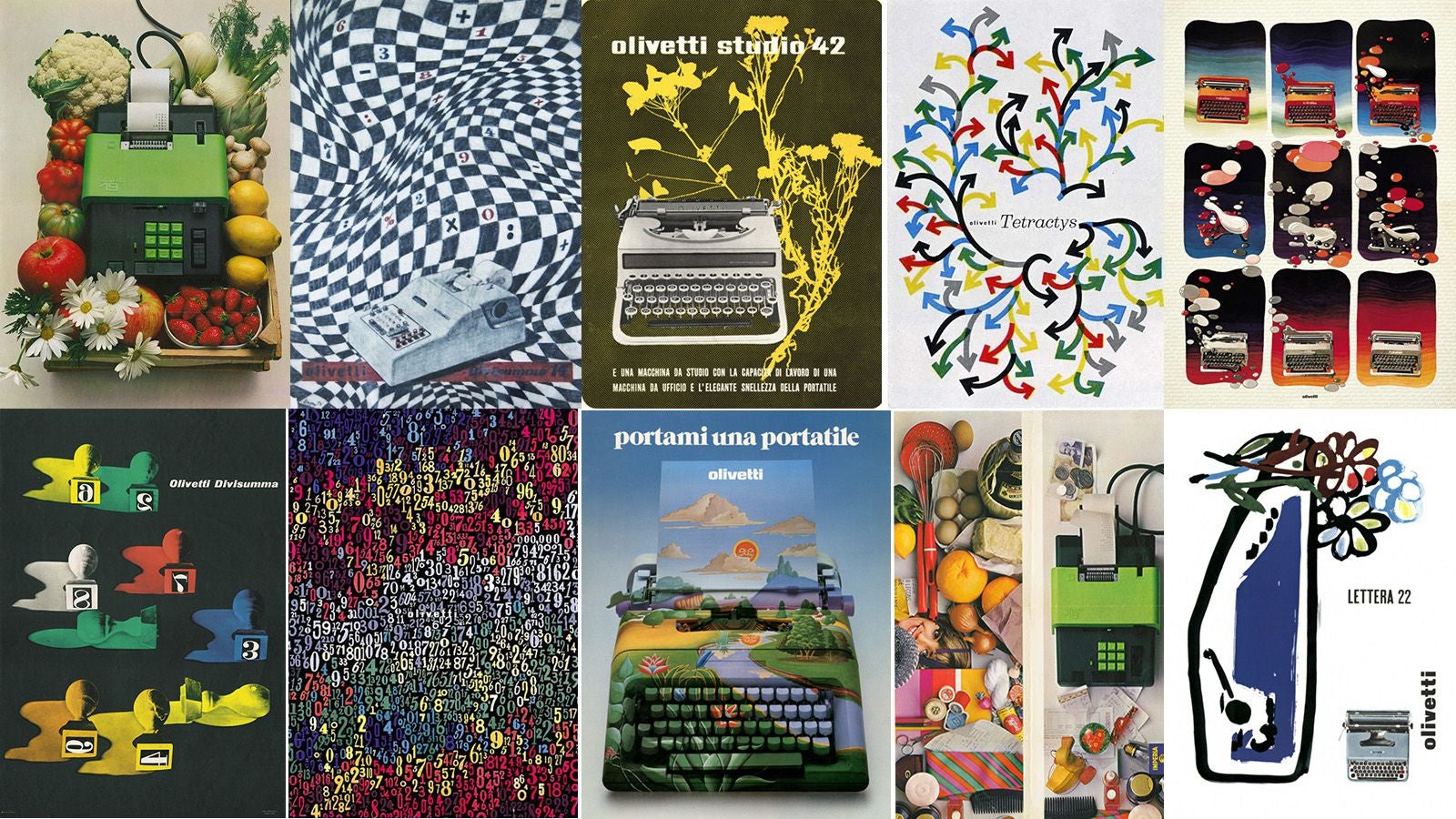

Under Adriano Olivetti’s guidance, the company grew from an establishment of under 900 employees to a multinational corporation with nearly 80,000 workers in 10 factories in Italy and 11 abroad (including US, Argentina, Brazil and Japan). The company evolved its production from mechanical calculators and typewriters to computers, printers and several other electronic devices, particularly for businesses. Here’s how it became a pioneer of innovation.

Innovation is the best investment

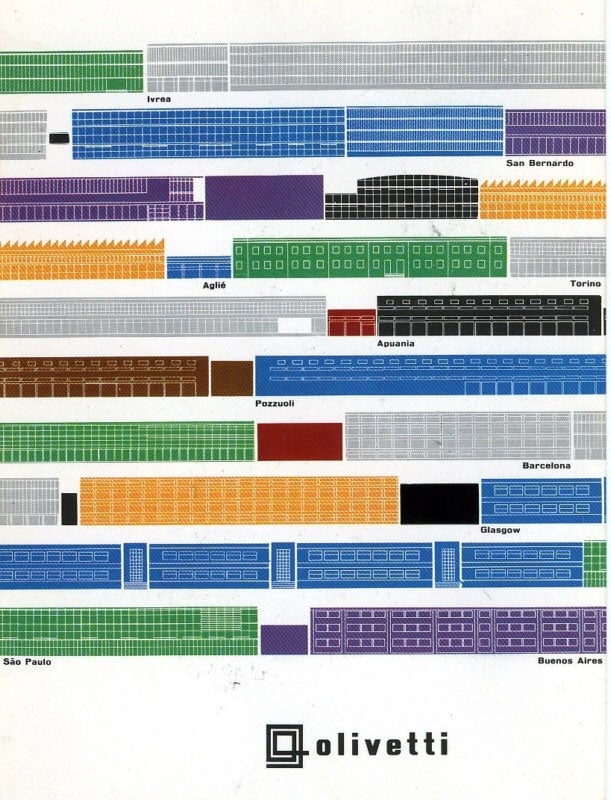

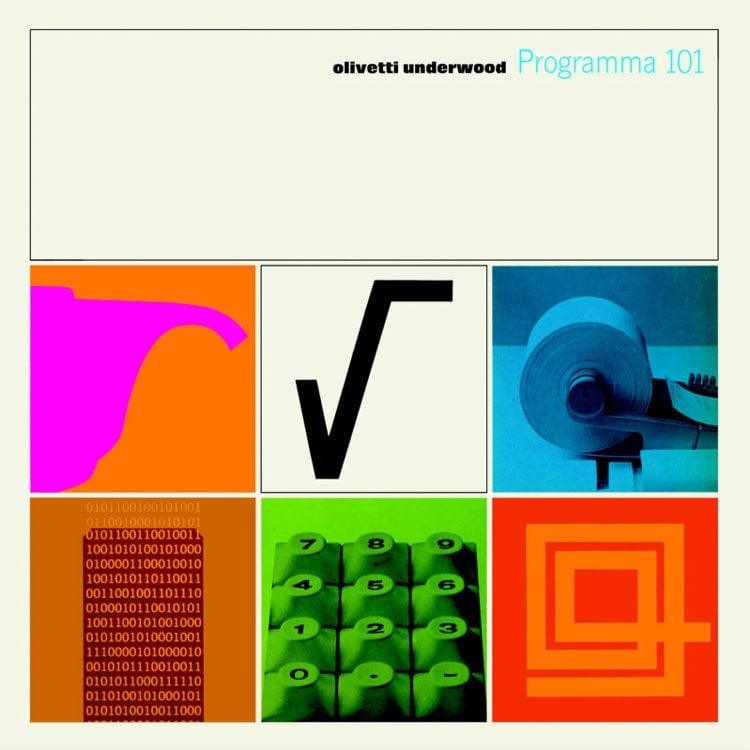

Olivetti’s first competitive advantage was in its products, which were well-designed and technologically advanced. Innovation was at the core of the production strategy. Alongside the traditional typewriter, the company developed products that allowed it to grow in new markets, beginning with mechanical calculators, electronic typewriters, and eventually the world’s first personal computer, called Programma 101 (P101), in 1964. In the late 1950s, the mechanical calculators were selling at a price comparable to that of a car (a Divisumma calculator was sold for 325,000 lire, and a FIAT 500 would be 465,000 lire)—with a margin of profit of over 70%.

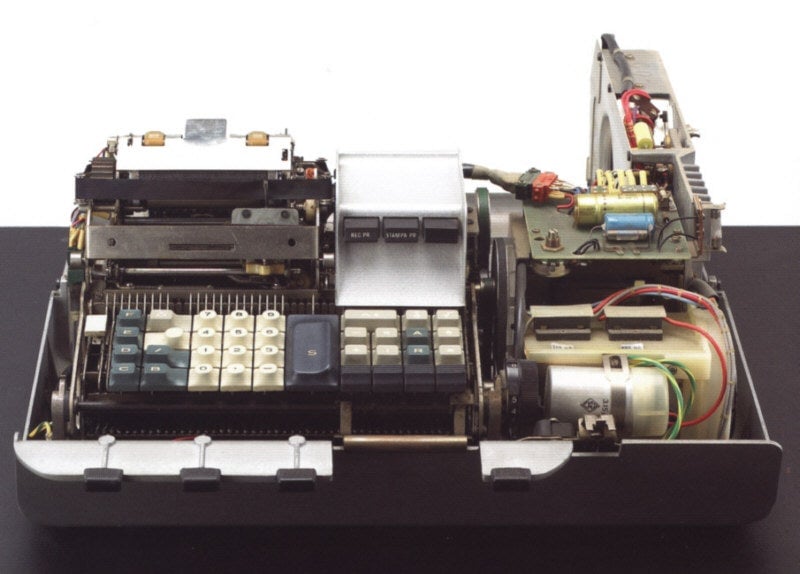

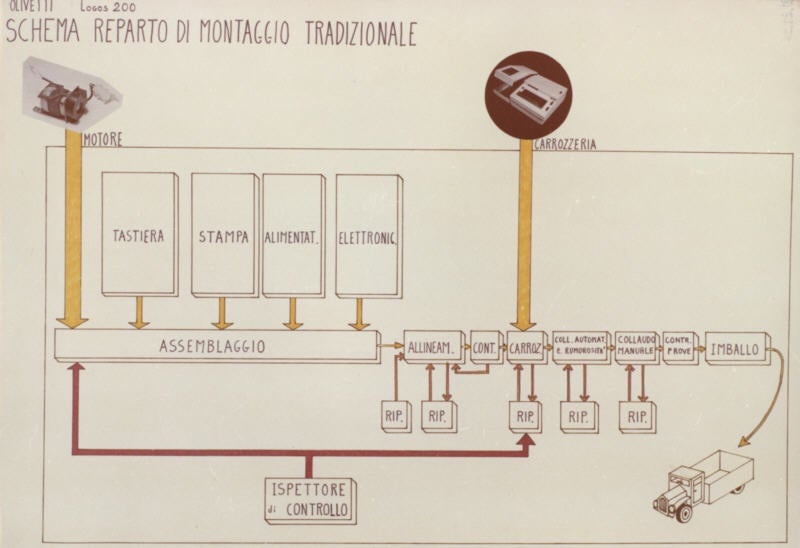

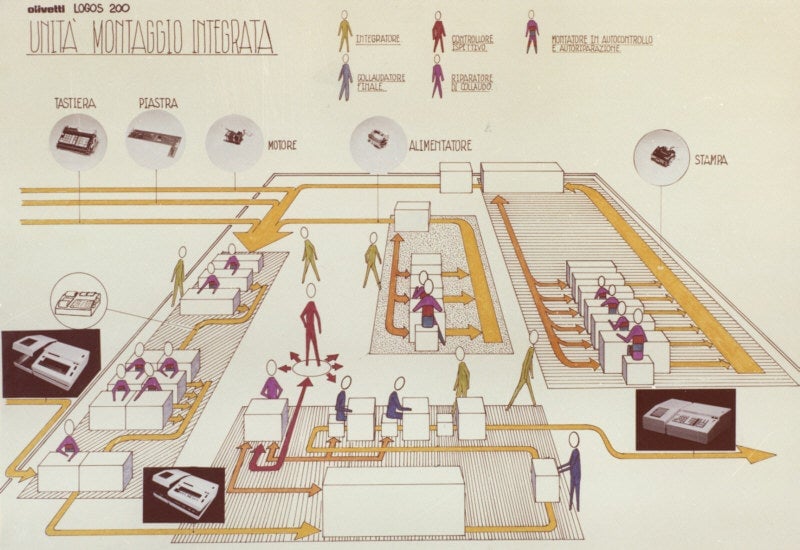

Innovation was built into the workflow. In the 1970s, Olivetti designed and implemented the ”integrated building unit,” inspired by the progress that companies such as Philips and IBM had made in moving away from the assembly like. This was an organization of work of moved away from the depersonalizing assembly line with the aim of giving workers more ownership over the entire manufacturing process. This resulted in higher productivity as well as the need for workers with higher qualifications whose wages were already 50% higher than the Italian average and could continue to grow as a result of the success.

“Design is a question of substance, not just form.”

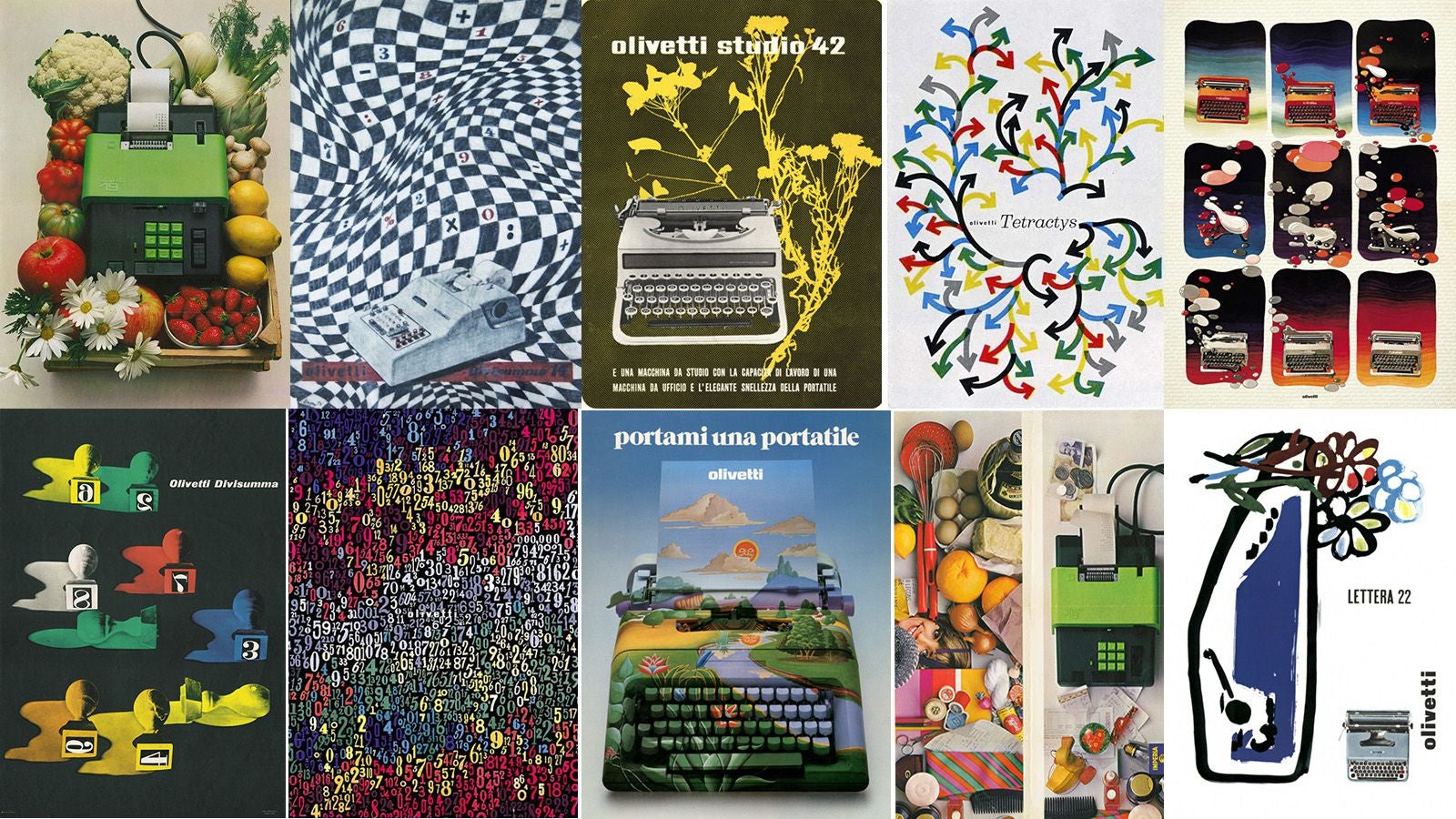

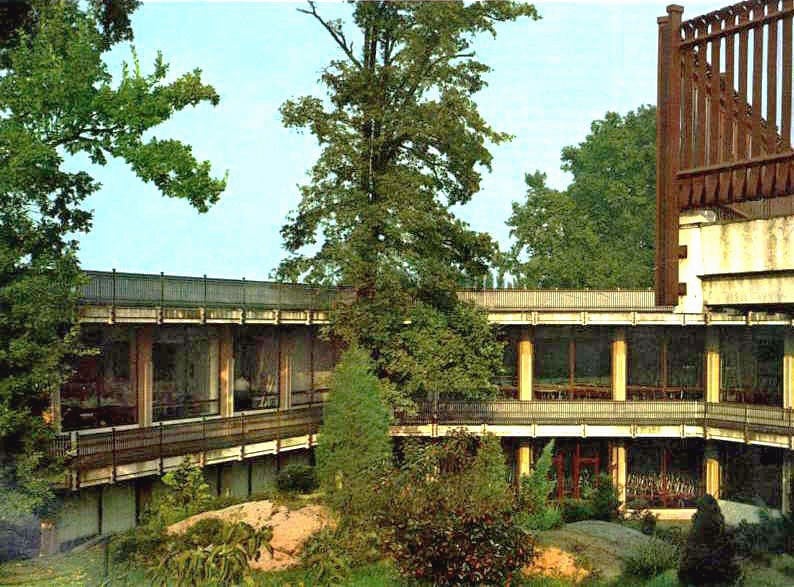

Olivetti’s eye for design showed through much of the operations—from the products to the advertising to the company buildings.

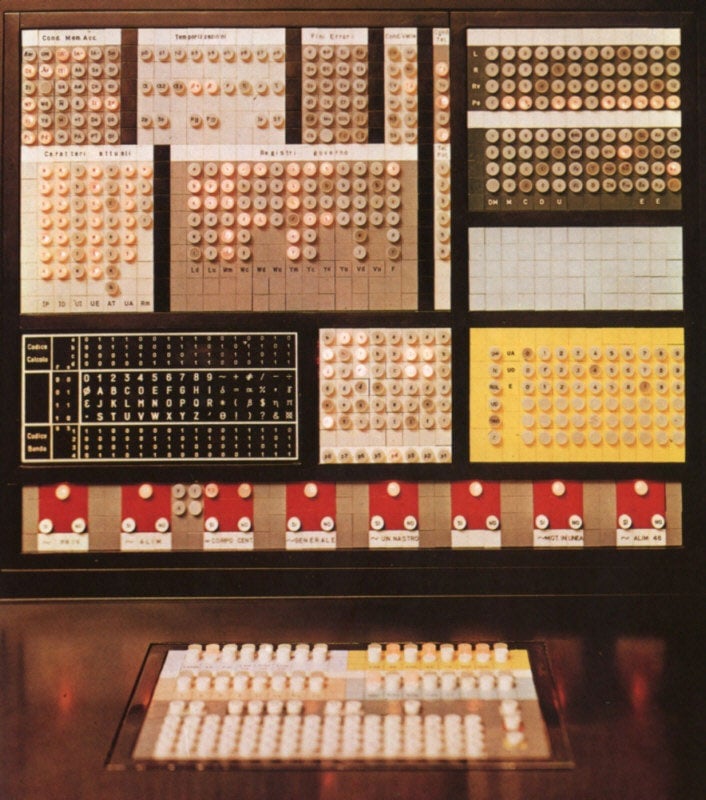

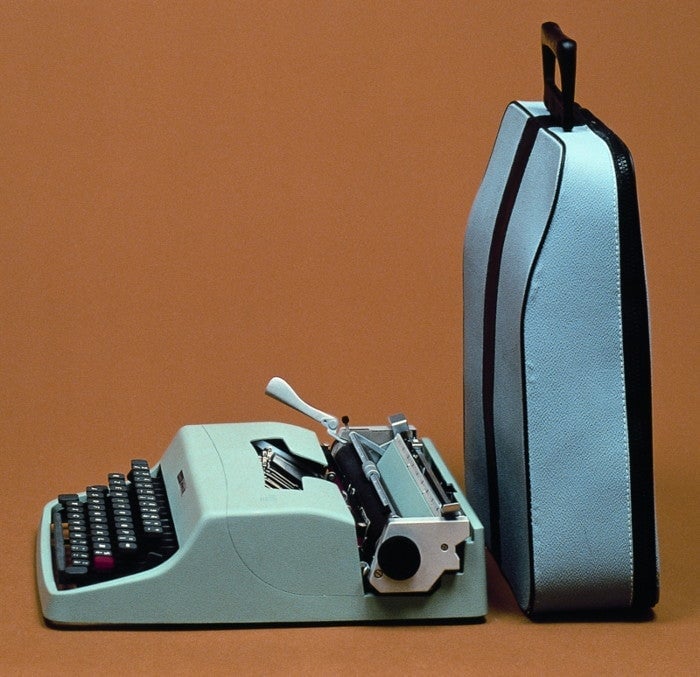

He employed famous designers to design his typewriters, many of which gained a spot in the New York Museum of Modern Art’s collection for the innovations they brought to the traditional typewriter design.

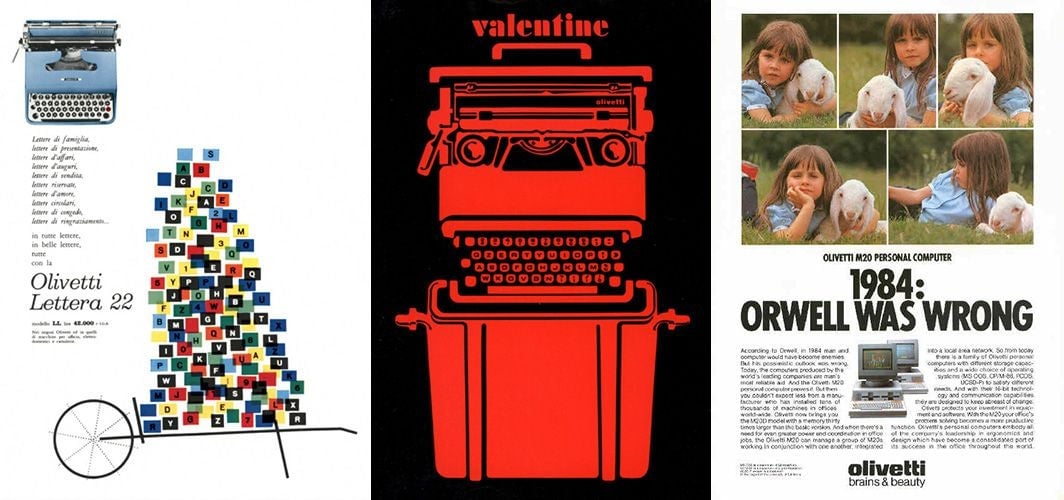

Designer Marcello Nizzoli was the creator of Lettera 22 and, a few years later, of Lettera 32 (a favorite of Cormac McCarthy). Ettore Sottsass and Perry King, designed the iconic red portable Valentine.

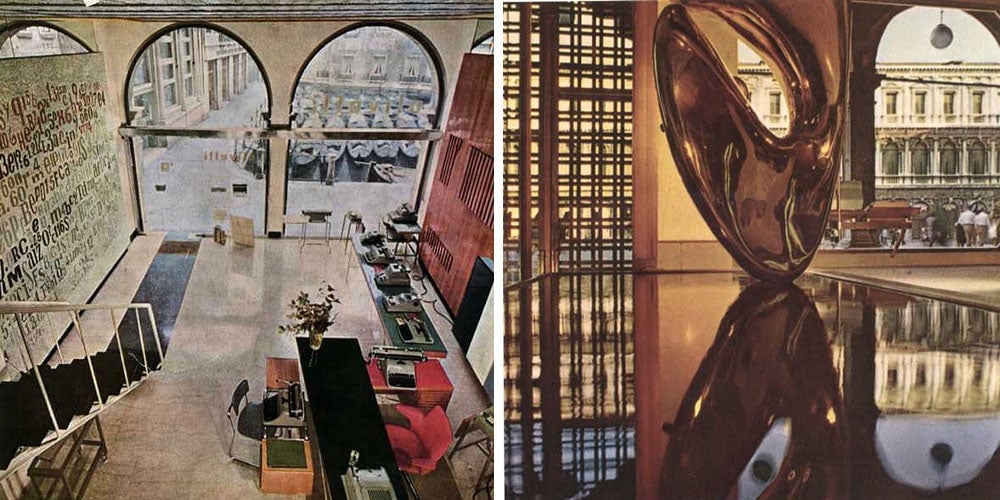

Design was also the distinguishing trait of Olivetti’s stores. Designed by pioneers of architecture (Carlo Scarpa and Gae Aulenti amongst others), the showrooms displayed a clear attention to the aesthetic as well as functionality: While the typewriters were displayed in a way that allowed customers to observe them in details and try them out, ample space was left to the display of art pieces.

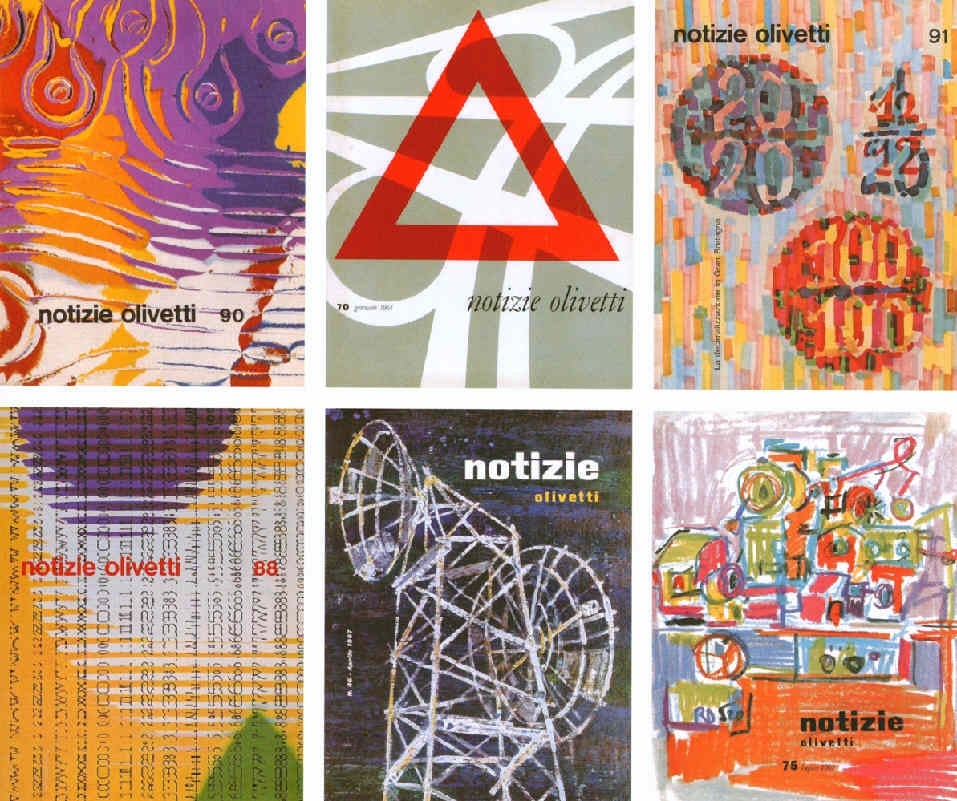

In promotional posters for his products, no element of communication was neglected: from the logo to brochures to pamphlets announcing internal services for the company, every detail was overseen by renowned graphic designers and artists, rather than being delegated to an external advertising or communications agency.

The commercials, while often more traditional than the print communication, also reflected the design sensibility of the company, like this ad about writing as a gift:

Less ping pong tables, more nurseries

The company maintained a peculiar link to the city of Ivrea where it was founded. It was Olivetti’s belief that the factory should be the core of the local community, and the center of the social and political structure. This meant a focus on conditions of workers, a move motivated on Olivetti’s part, by respect and gratitude, which had the effect of increasing workers’ loyalty toward their employer. Not only was turnover negligible, but in the main Ivrea factory, Granelli told Quartz “fathers and sons worked together, and the employment of families [of workers] was encouraged and sought.”

Aside from the higher salaries, it was the benefits that set Olivetti apart as an employer. Social services, with particular attention to women and children’s wellbeing, were provided to employees and the communities that surrounded the factories. Ahead of the 1950 Italian law guaranteeing maternity leave for five months, the company offered its female workers nine-and-a-half months maternity leave (paid at 80% of the full salary) as well as full coverage of medical expenses, including training for breast-feeding and nutrition, and free pediatric services for children of employees up to 14 years of age. At a time when women were highly discriminated against, of Olivetti’s first 250 employees, around 40% were women.

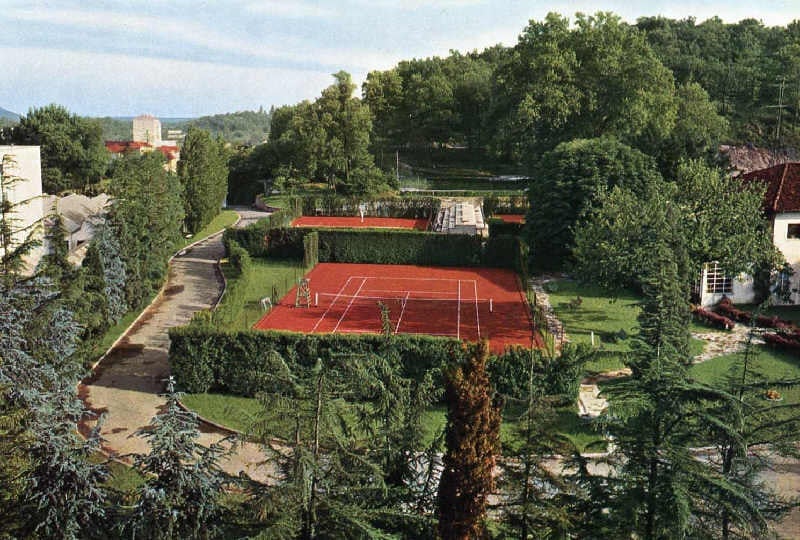

The company financed a network of medical clinics operating for free in the areas around factories in Italy. It also set up nurseries and kindergartens for nominal fees as well as subsidized after-school services for the children of workers. Summer camps and holidays—mostly free—were also attended by the employees’ children. Kids had access to specific educational programs with the aim of, as Olivetti wrote in his book Services and social assistance in the factory, “raising the child in a rational and modern way, not only from a physical point of view, but also with specific educational criteria.”

These initiatives and social services were implemented with input from the workers, who were represented in a “management council.” Employees also worked shorter hours than the Italian average—45 per week, versus the usual 48—and could dedicate part of their time to self-improvement and training through company-sponsored courses.

The so called ”Olivetti welfare” wasn’t motivated by tax cuts or subsidies—on the contrary, some of the policies were carried on in spite of the fascist government and after the war, while Italy emerged from deep poverty and destruction. While the Olivetti example remains the most iconic, other Italian companies have adopted measures aimed at improving the lives of workers and some, such as company-subsidized holidays, canteens and recreational activities are still in place in several organizations (Telecom Italia and ENEL amongst the big ones, or Loccioni, a smaller company that, according to Granelli, follows Olivetti’s ethos).

Spice up your company culture with some actual culture

“We must go beyond separations between capital and work, industry and agriculture, production and culture,” Olivetti wrote. The factory, he believed, had to be in service to the people. One way to do this was to invest industrial profits in culture, which he saw as a necessary support to technology.

The core of the cultural activities was the large factory library in Ivrea, where both employees and citizens had access to books as well as a large selection of local and foreign newspapers and magazines (reportedly 2,500 titles). The library was also the place where the company’s cultural association—led by well-known intellectuals—would organize concerts (often during the two-hour long lunch break) or talks with established artists.

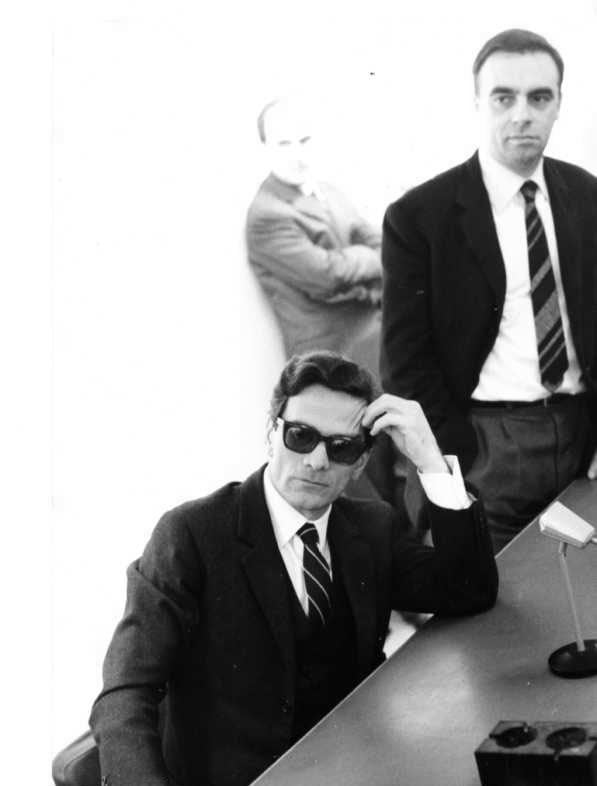

Olivetti also involved poets, writers, and other intellectuals in the actual running of the company: Psychologist and novelist Ottiero Ottieri, for instance, was in charge of recruitment; Giovanni Giudici, a poet, ran the company’s library. The motivation was to run an inspired business and expose workers to the thinking of minds trained in different disciplines.

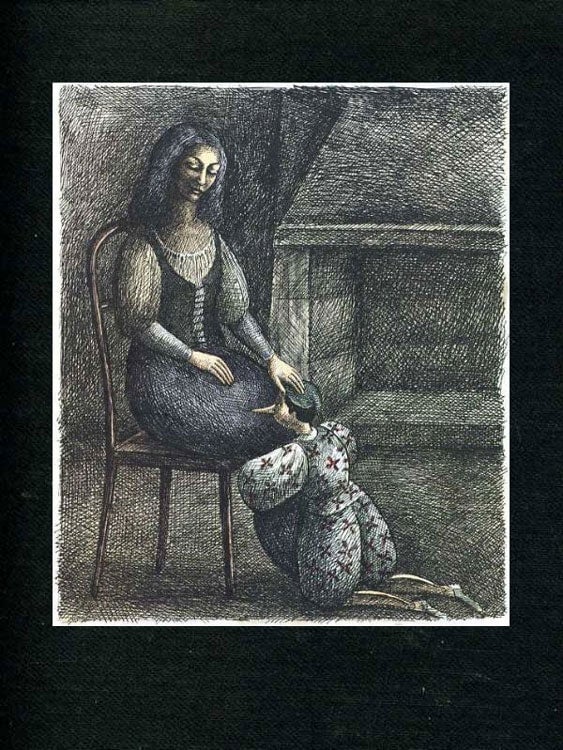

Culture and art were made part of many aspects of the company life: At Christmas, employees would receive special editions of classic books, or custom-made calendars with illustrations by emerging artists or reproductions of famous artworks. Further, the company would sponsor the renovation of masterpieces such as Leonardo Da Vinci’s “Last Supper,” which took 17 years and the equivalent of over €3 million ($3.3 million).

Idealistic as it might seem, Olivetti’s culture was sustainable—and it was in fact sustained for many years. This is why, of all the definitions given to his experiment, Olivetti would reject the term (link in Italian) “utopian” more strongly than any:

“Well, if I might, often the term utopia is the easiest way to sell off what one doesn’t have the will, capacity or courage to do. A dream seems a dream until you begin to work on it. Then it can become something infinitely bigger.”