Throughout 2015, a mosquito-borne virus has expanded its reach across Latin America. Now, the Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC) has confirmed at least eight cases of Zika virus in the US among residents returning from abroad.

Those infected can suffer from red rashes, fever, and joint pain, or they can remain symptomless. The real worry, as Brazil’s health ministry has been warning its citizens, is the suspicion—as yet unproven—that women who catch Zika may give birth to children with microcephaly, a neurological disorder that gives them abnormally small brains. Many children born with microcephaly die young, and those who survive suffer serious problems, including speech and learning difficulties, trouble with balance and coordination, dwarfism, and seizures.

Brazil, at least, is convinced Zika causes microcephaly. “Before the explosion of cases since mid-2015, Brazil had an average 150 cases of microcephaly a year. Today I can tell you that we have 100% certainty of the connection of the Zika virus with increasing cases of microcephaly in Brazil,” Marcelo Castro, Brazil’s health minister, told the Wall Street Journal (paywall).

However, it’s not understood how the virus might cause the disease. And even the statistical correlation isn’t always apparent, as Quartz reported earlier:

A 2007 outbreak on Yap Islands in Micronesia is estimated to have affected nearly 75% of the population of some 12,000 people, and a 2013 outbreak in French Polynesia affected nearly 28,000 of 270,000 residents. Neither epidemic caused a spike in microcephaly.

One hypothesis is that only a tiny proportion of pregnant women with Zika give birth to babies with microcephaly, and that the connection was only noticed now because Brazil has had so many Zika cases—as many as 1.5 million, according to the Brazilian government, though accurate numbers are not available.

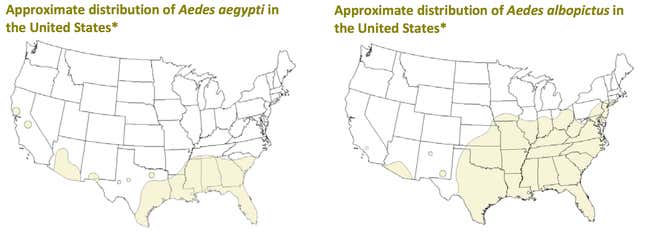

There is as yet no vaccine to prevent or medicine to treat Zika. The US is home to two species of Aedes mosquito (A. aegypti and A. albopictus) that are thought to carry the virus. Apart from the eight confirmed cases, the CDC is receiving specimens for other travelers who have shown Zika-like symptoms.

The good news for Americans is that—apart from in Puerto Rico—there are as yet no locally transmitted cases of Zika virus in the US. The CDC recommends that people take the same precautions as they would to avoid mosquito bites: carry insect-repellent creams, wear long sleeves and pants, sleep in air-conditioned rooms or behind windows with screens.