Look around at all the new sushi joints and the lobster roll trucks. We’re taking a heck of a lot of fish out of the sea. Luckily, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), which tracks how many we’ve been catching, says catches have remained fairly stable for nearly two decades—a reassuring sign.

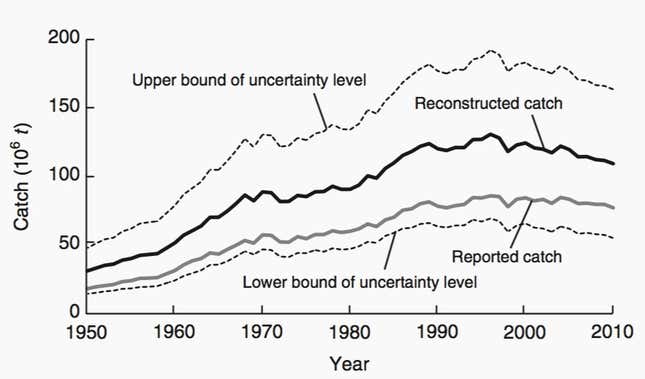

But that’s probably wrong. Even way wrong. Over the last six decades, we’ve plucked at least 50% more fish from the ocean than official data told us, suggest data reconstructions by Daniel Pauly and Dirk Zeller of the University of British Columbia, in a Jan. 19 paper in Nature Communications.

The researchers tracked a steep decline since the mid-1990s, which could mean seafood is growing scarcer, upping food security risks. In some places, we’re likely catching fish too quickly for them to replace themselves.

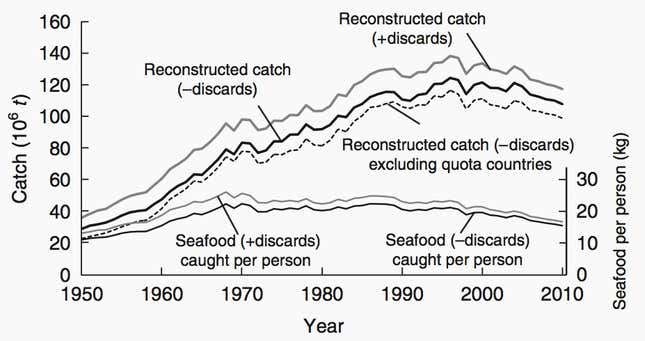

On the face of it, that decline isn’t necessarily a pure sign of overfishing. Discards—sea creatures killed in nets meant for commercial species—have been falling. And many areas in the US, northwestern Europe, Australia, and New Zealand have been slashing catch quotas to rebuild stocks.

Ominously, though, the researchers note that even after stripping out discards and sound management, a sharp drop in their reconstructed catch data remains.

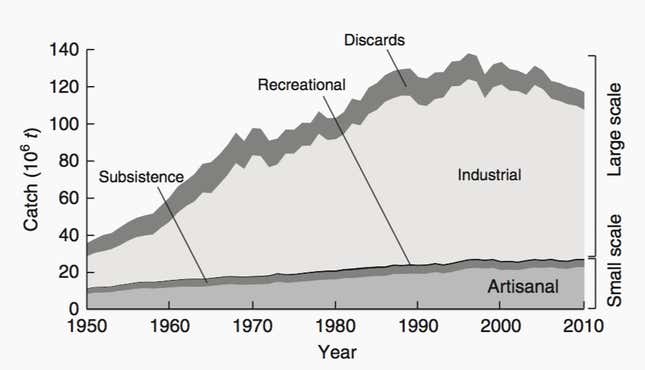

The biggest absolute decline comes from industrial fishing. “We’re fishing harder, but getting less out of it,” explained Boris Worm, a marine ecologist at Dalhousie University, to Quartz. Worm is not affiliated with the study. “It’s like squeezing a lemon harder, but getting less juice out of it.”

If that’s true, why doesn’t FAO data show the same deep drops in fish stocks?

There are two forms of fishing, explains Worm. There’s the easily visible, documentable form reported by law-abiding fishermen to their regulators, which eventually finds its way into the FAO estimates. But there’s also a ”hidden form”—for instance, illegally caught fish, or those landed by subsistence fishermen in poor countries. Pauly and Zeller have undertaken what Worm calls “the Herculean task” of finding, estimating, and adding up six decades worth of that ”hidden form.”

Asked about the significance of the new study, Trevor Branch, a marine conservation and statistics professor at the University of Washington, described it to Quartz as ”a huge effort to get more accurate data.” Branch is also unaffiliated with the study.

Pauly and Zeller do emphasize in their paper that they include fairly large uncertainty of these estimates, given the many assumptions on which they rely. In fact, the confidence intervals are so broad that they include the original FAO estimates, notes Branch. ”I would not be too surprised if the results were correct, though,” he says.

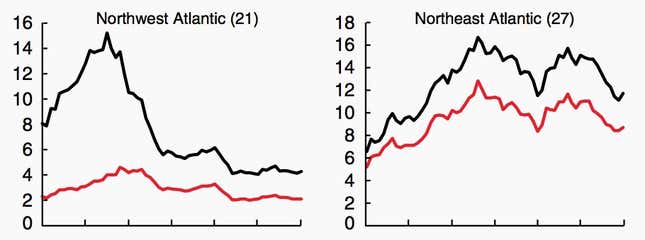

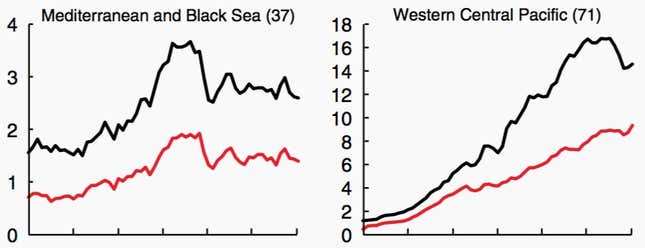

In addition to estimating a much higher global catch than the FAO, Pauly and Zeller’s paper offers evidence of huge regional variation between official and “hidden” fishing. In regions that are fairly well managed, the gap between reported and total catches is small, says Dalhousie’s Worm. “But even huge fisheries like the Mediterranean and Black Sea total more than 50% higher than what’s reported,” he says.

Here are the trends for the north Atlantic…

… and for the Mediterranean.

Unsettling—and as uncertain—as the results are, these data reconstructions offer a clearer glimpse of the bigger picture than we’ve ever had before.