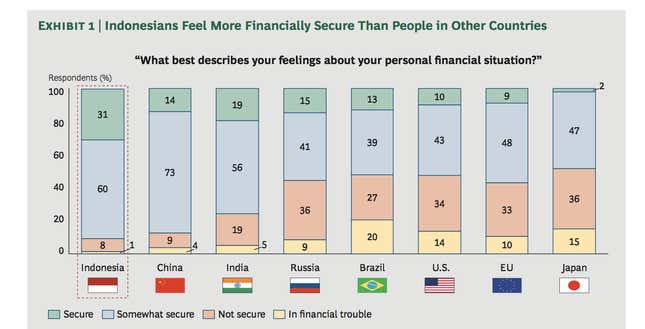

Indonesia is “Asia’s next big opportunity,” according to a new report from Boston Consulting Group, which cites its fast-growing economy (up 6.2% last year, forecast to grow 6.8% in 2013) and favorable demographics. Over 60 per cent of the population is between 20-65, which gives the country a large bank of earners and not too many old people for workers to support. And while most Indonesians live in relative poverty, lacking air conditioning, broadband and access to healthcare, their cheery optimism about the future makes them happy to spend what they have. The nation’s consumer sector is thriving, and BCGs data shows 91% of Indonesians feel at least somewhat financially secure—a higher percentage than the US, the EU, or Japan.

But such studies often gloss over the fact that Indonesia is a potential minefield for foreign investors. The country has drawn multinational retailers like bees to honey, but the government plans to enact a cap on foreign restaurant chains. And Canada’s Fraser Institute says Indonesia is the least attractive place in the world for miners. The country last year decreed that mines must be majority owned by Indonesians within ten years, which could force foreign diggers to shed stakes in their projects before they have made a return on investments.

The chief executive of a Sydney-listed resources company operating in Indonesia, who asked not to be named as the topic is sensitive, told Quartz: “Indonesia is definitely the most difficult place I have worked, and I have led projects and investments in the Democratic Republic of Congo and South Sudan.” Transparency International places Indonesia 118th on its 176-nation “Corruption Perceptions Index.” According to the Australian CEO, official graft in Indonesia is worse than notoriously corrupt parts of Africa because “African officials communicate the bribes they want very clearly. So you go to your country’s embassy and get help negotiating a non-corrupt solution. In Indonesia, I can never work out what officials are asking us for. It is clear they want kickbacks for project approvals, the requests are opaque and change constantly.”

Still, BCG forecasts the number of middle class and affluent consumers in Indonesia will double by 2020 to roughly 141 million people. Vaishali Rastogi, a BCG partner and co-author of the report, says: “The CEOs we talk to are extremely positive about the opportunity this presents.” Capitalizing on that opportunity, however, may be a more difficult proposition.