India’s massively delayed nuclear power programme could see a resurrection after Électricité de France (EDF), the world’s biggest electricity company, signed the dotted line to set up six nuclear plants in the country.

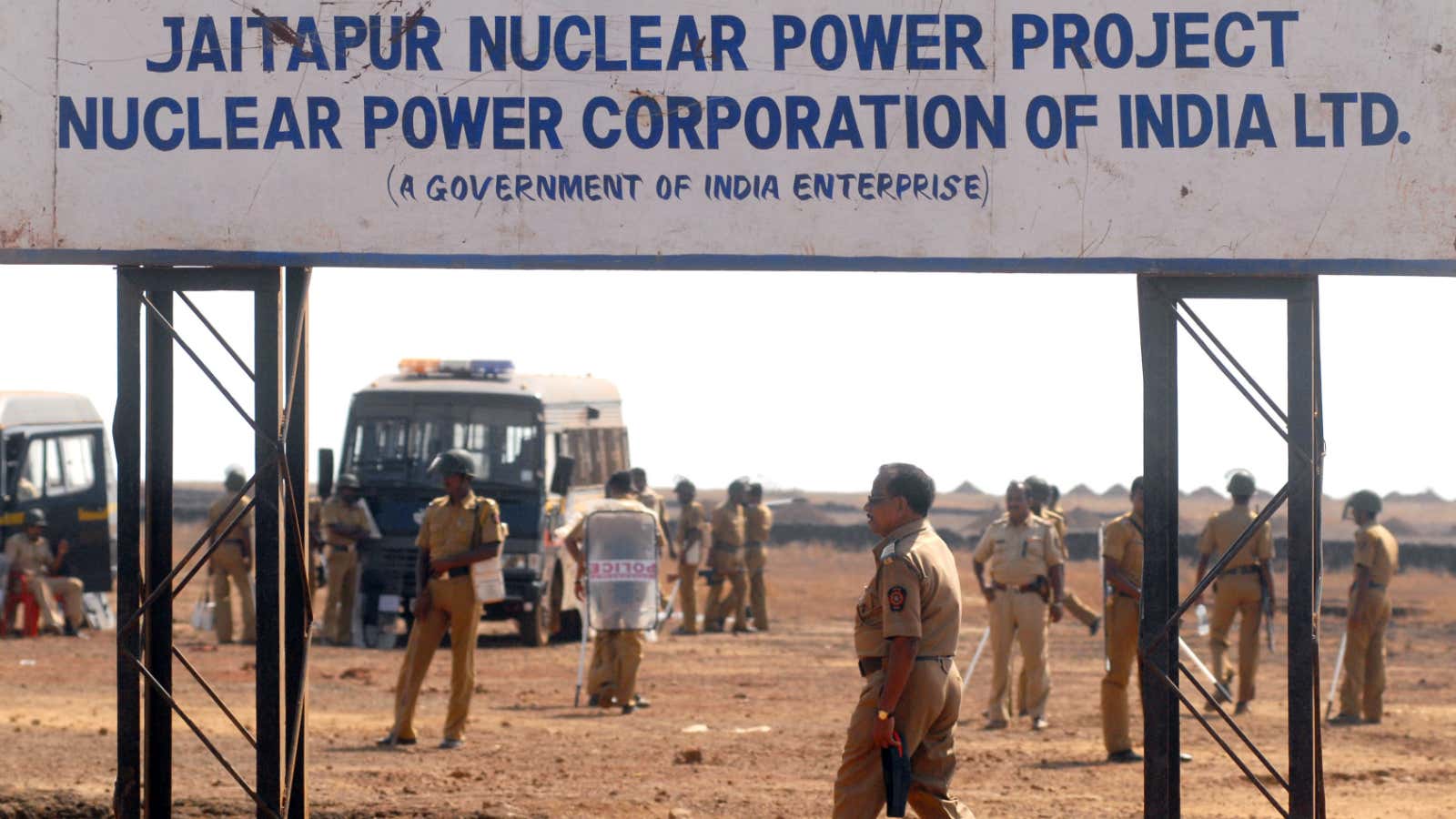

On Jan. 26, EDF announced that it has signed a memorandum of understanding with the Nuclear Power Corporation of India (NPCIL) to build six reactors. The power plants will come up in Jaitapur, a coastal village in the western Indian state of Maharashtra. The deal was signed during French president François Hollande’s recent visit to India.

EDF is taking over the project from Areva, which won the contract in 2009. The company, which is 84% owned by the French government, was widely expected to undertake the project after it acquired a majority stake in Areva in July 2015.

Areva, also majority owned by the French government, didn’t find much success in operationalising the project mostly due to disagreements with NPCIL over the cost of the project and opposition from locals who fear environmental damages. Jaitapur is located in a seismically active zone.

“The Jaitapur project is at a stage of preliminary technical studies,” a press release from EDF said. ”It was also given initial environmental clearance in 2010.”

The Jaitapur project is expected to become the world’s biggest nuclear contract and one of the world’s largest nuclear sites. The 10,000 mega watt (MW) project will have six reactors of 1650 MW each.

India currently operates 21 nuclear power reactors with an installed capacity of 5,780 MW, and the Jaitapur project is crucial to kickstarting its flailing nuclear energy programme. So far, the Indian government has only managed to meet a little over 30% of its target of installing 17,400 MW by 2017. Much of that is due to a lack of interest from foreign reactor makers, who have objected to a law that holds manufacturers liable in case of an accident.

In September 2015, for instance, General Electric decided not to invest in the nuclear energy sector in India over uncertainties regarding the liability law. “The world has an established liability regime, it has been accepted and adopted. I can’t put my company on risk. India can’t reinvent the language on liability,” Jeff Immelt, General Electric’s CEO, had said.

In a joint statement issued by Hollande and Indian prime minister Narendra Modi on Jan. 25, the leaders said that they plan to “conclude techno-commercial negotiations by the end of 2016” and to begin operations at the plant by “early 2017.” It is not clear how the companies will work out modalities regarding the liability clause.

“The goal in the next few months is to continue with the work initiated by Areva and NPCIL in April 2015 to secure certification for the EPR reactor in India from the Indian safety authorities and finalise the economic and financial conditions and the technical specifications of the project, supervised by the Indian atomic organisation DAE,” the statement from EDF said.

India currently faces a severe power shortage and the Modi government is looking at nuclear energy to bridge that gap and bring electricity access to some 300 millions Indians. About 60% of the electricity generated in India comes from its coal-powered plants while nuclear power contributes just about 3.5%.