This is an article from 2016. Read our most recent coverage of the Doomsday Clock: In 2022, the Doomsday Clock didn’t change for the second year running

The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists has announced that it is not moving the minute hand of its “Doomsday Clock” any closer to midnight.

While it’s nice knowing the prospects for the continuation of humanity are no worse than they’ve recently been, we also aren’t any safer. The keepers of the clock say there are still enough threats out there to offset whatever bullets the world might have dodged by reaching a climate-change deal in Paris and by getting Iran to agree to diminish its nuclear capabilities. And so the group is not moving the clock’s hand back from midnight, either.

This item is about the 2016 update to the Doomsday Clock. In 2021, the Doomsday Clock remained at 100 seconds to midnight.

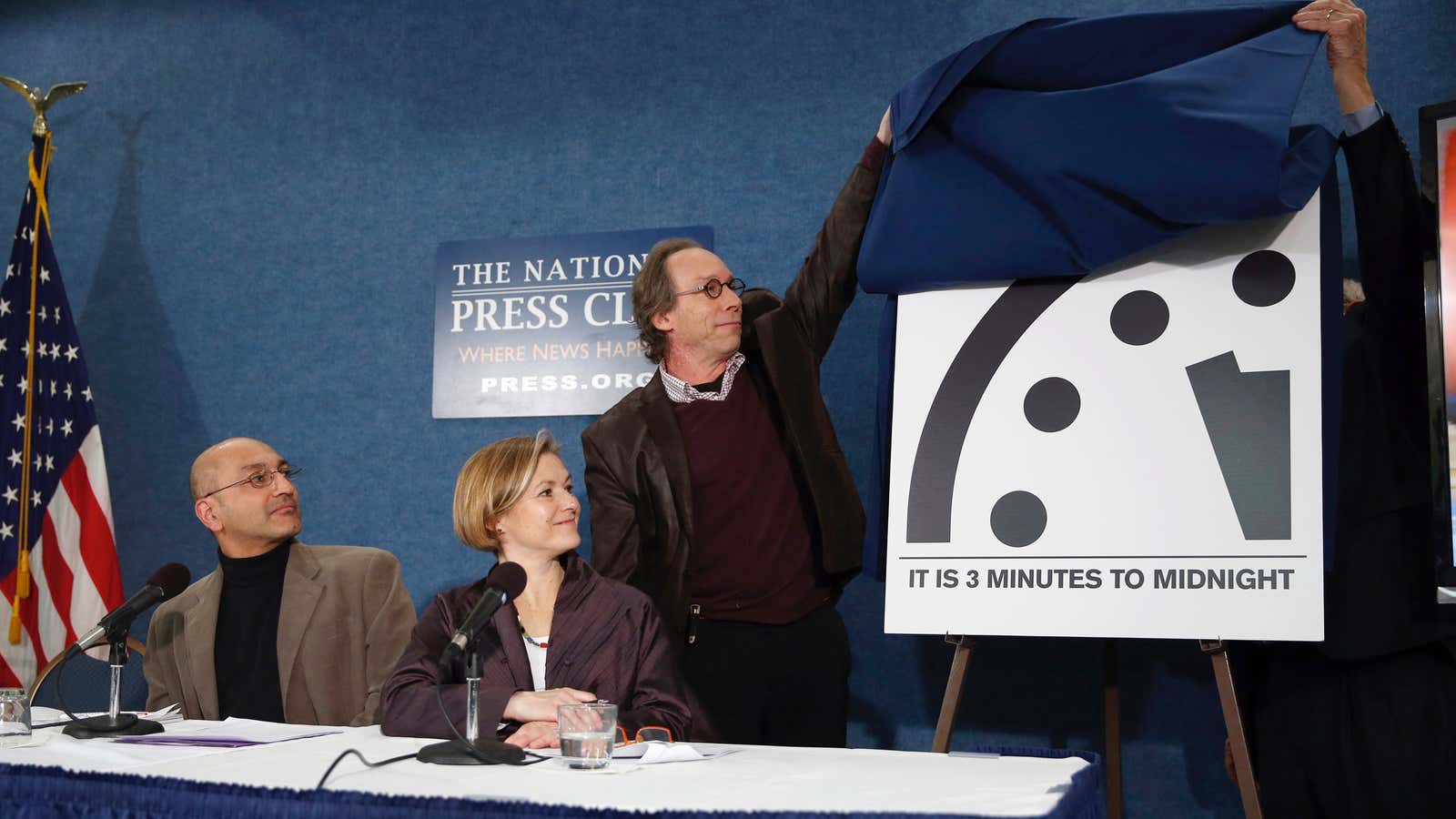

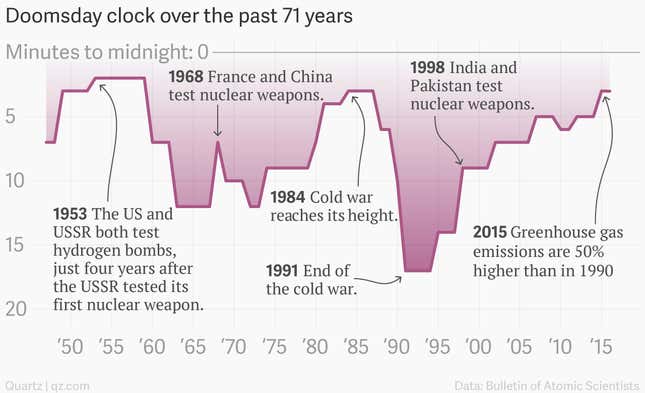

The metaphor of the Doomsday Clock—developed by a group of scientists in 1947, including the father of nuclear bomb, Robert Oppenheimer—is an attempt to show how close humanity is to a catastrophic event, which is represented by midnight on the clock face. Last year, the Bulletin set the clock to three minutes to midnight, implying a level of threat to the world that hadn’t been seen since the Cold War.

“The decision not to move the hand of the Doomsday Clock in 2016 is not good news,” said Lawrence Krauss, a theoretical physicist who sits on the board of the Bulletin, “but an expression of grave concern.”

Much of the contemporary threat, the Bulletin said in a presentation today (Jan. 26) in Washington, revolves around the same actors who drove the group’s concerns during the Cold War: the US and Russia. The Bulletin suggested that Russia’s recent nuclear posturing, and both countries’ rebuilding of their nuclear arsenals—instead of disarming themselves of nuclear weapons—pose clear threats to the world’s safety.

Climate change also was cited as a major issue—while calling the Paris climate accord a “tentative success,” the group noted that 15 of the 16 warmest years ever recorded have been experienced since 2000.

While the Bulletin’s outlook for humanity sounds pretty bleak, it did suggest an overarching, six-point plan to save on the world. It involves dramatically reducing the spending on nuclear programs, returning to the disarmament programs, engaging North Korea over nuclear arms, following up on the Paris climate treaty, properly managing nuclear waste, and mitigating potentially catastrophic uses of new technology, such as the weaponization of artificial intelligence. Shouldn’t be too hard, then.