Could a rum by any other name taste as smooth?

As the US and Cuba press ahead with their plans to normalize relations, a global intellectual-property dispute between the booze conglomerates Pernod Ricard and Bacardi—a conflict that has its origins in the Cuban revolution—is breaking out once again.

At issue are the rights to the Havana Club rum brand, which have been carved up for close to 20 years. Pernod Ricard markets the liquor around the world on behalf of Cuba’s socialist government—except in the US, where Bacardi claims the trademark, which it purchased from the exiled Cuban family that created it.

While neither spirits company has been happy with the configuration—particularly Pernod Ricard, which has made multiple efforts over the years to wrestle the US rights away from its rival—it seemed there was little maneuvering room left for either side.

But a sudden decision by the Obama administration—one that appears to contravene the 1998 law that effectively put the US rights in the hands of Bacardi—has re-opened the battle, which is now playing out on everywhere from the US courts to the World Trade Organization.

As is usually the case with global brand disputes, there are significant amounts of money at stake. But this one inflames the participants’ passions more than most, because tied up in this conflict over sugar spirits are each side’s claims to Cuban authenticity.

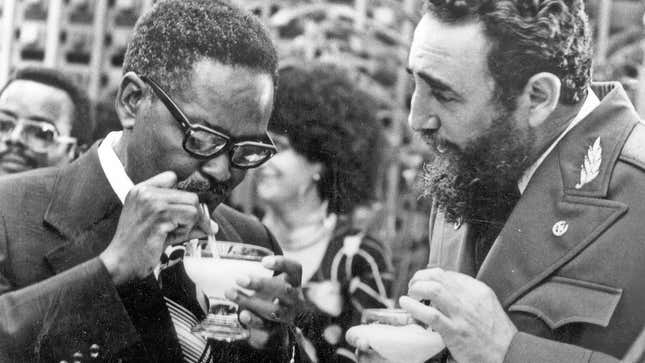

Rum and revolution

Rum distilled from Cuban molasses became a global favorite under the guiding hand of the Bacardi family company, which began distilling in 1862 and won its first international competitions in 1901. It earned its advertising tagline, El Que a Cuba Ha Hecho Famosa (“the one that made Cuba famous”). Even today, it is the world’s best-selling rum brand, though it is no longer made in Cuba.

Pioneers of more than just distillation and distribution, the Bacardi family, and particularly Pepín Bosch, the canny overseer of the company from 1944 to 1976, understood the preeminent value of a global brand, as Tom Gjelten explains in his fascinating book on the company.

In 1957, the Bacardi clan secured the global rights to the family name and to the brand for fear that the corrupt dictator Fulgencio Batista might threaten them. But it wasn’t until 1960, after the triumph of Fidel Castro’s revolution—which the Bacardis themselves had helped finance out of nationalist feeling as much as business interest—that the family would need to rely on these measures.

As Castro began to embrace socialism and nationalize companies, Bosch began to fear that his family’s company was next, and he took the key step of sneakily mailing the original trademark certificates to New York. He, his family and many of his employees would follow them into exile by plane. The Cuban government would soon seize Bacardi’s distilleries, declaring the creation of the new Compañía Ron Bacardi (Nacionalizada).

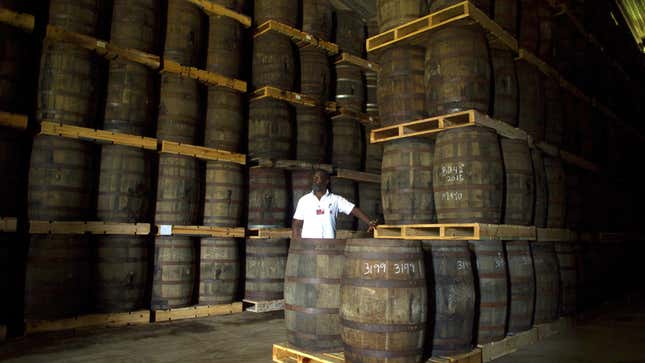

But the exiled family was able to rebuild its rum empire. It managed to do so mainly because of legal victories securing the rights to market “Bacardi,” and because of the distilleries it had established in Puerto Rico and Mexico. The Cuban government would eventually be forced to favor another nationalized firm, Bacardi’s erstwhile rivals Havana Club, whose owners, the Arechabala family, hadn’t moved their distillery or intellectual property overseas.

By the 1970s, hundreds of thousands of cases of nationalized Havana Club were being sold abroad to fund the revolution.

The Rum Wars of the 1990s

The vast majority of Havana Club sales were coming from a geographically specific set of customers—governments in the Soviet Union and the eastern bloc. But with the collapse of communism, this market disappeared, and Castro’s regime was forced to take its first steps toward economic liberalization: In 1993, Pernod Ricard, the French liquor conglomerate, won the rights to market Havana Club internationally in a deal that reportedly paid the regime $50 million.

The prospect of seeing their foes in Cuba’s government paired with a sophisticated multinational liquor distributor dismayed the Bacardis. By 1997 they had paid $1.25 million to the Arechabala family for the right to the Havana Club trademark—which in reality just gave it the right to fight Cuba for the Havana Club trademark. The Arechabalas had never disputed Cuba’s use of their rum name before, and it had been registered legally by the Cuban government after the original trademark lapsed.

Bacardi challenged the trademark in the US on the grounds that it had been seized without recompense by the Cuban government, and took the case to a federal court. The company soon had an ace up its sleeve: Foes of Cuba in the US Congress tucked a provision known as Section 211 into a major spending bill. It said the US could grant no trademark to a business seized by the Cuban government. The judge had little choice but to rule in Bacardi’s favor.

Frozen in time

Since then, Bacardi has marketed ”Havana Club” rum in some of its US markets, particularly Florida. But Pernod Ricard sells around 3.8 million cases a year of Cuban “Havana Club” everywhere else in the world.

Pernod Ricard has continued its legal skirmishes, including a failed lawsuit arguing that selling Puerto Rican rum in a Havana Club bottle is misleading. In 2006, the US Treasury Department office in charge of sanctions ruled that Cuba was ineligible to pay the $500 fee to renew its Havana Club trademark, because even accepting the payment would be a violation of US law. The trademark was then canceled.

Or was it?

After the US Supreme Court declined to take their case in 2012, Pernod Ricard’s lawyers complained to the US trademark office that the circumstances of the Cuban embargo should not have caused the trademark to expire. Instead, they argued, the trademark would have to be as frozen as the US-Cuban relationship until the embargo was lifted.

Meanwhile, US policymakers had an added incentive to let sleeping dogs lie—which was the knowledge that more than 6,000 US corporate trademarks were registered in Cuba, both in anticipation of future trade and to prevent brand theft, and could be subject to retaliation. At one point in the saga, Castro even threatened to market his own Coca Cola.

Rum wars redux

On Dec. 17, 2014, US president Barack Obama and Cuban president Raul Castro simultaneously announced efforts to normalize relations between the two countries. Both reopened embassies after a mutual prisoner exchange and a US executive order relaxing some sanctions, including on payments between the two countries.

On Jan. 18, 2016, Pernod Ricard announced that the Cuban government had been allowed to submit a payment to renew its trademark registration temporarily and could seek a 10-year renewal.

The news incensed Bacardi. The company said it was “shocked” that the Obama administration “has taken actions to allow the Cuban government to attempt to resurrect this dead registration.” It promised to continue fighting for the name it believes it has the full rights to since it was purchased from the Arechabalas.

Today (Feb. 1), Bacardi said it has filed a Freedom of Information Act request with the US Treasury Department to learn, in the words the company’s general counsel, “the truth of how and why this unprecedented, sudden and silent action was taken by the United States government.” Bacardi is seeking all documents used or maintained by the Treasury Department, the State Department, the White House, the National Security Council, and the US Patent & Trademark Office in relation to the Havana Club trademark registration action.

If Cuba regains possession of the trademark, it’s still not clear how it would survive a legal challenge under section 211, which still invalidates trademarks connected to seized Cuban companies. But lawyers who have followed the case suggest a long game is in effect. They see Pernod Ricard’s initial lawsuits as an attempt merely to establish its legal rights; imports of Cuban rum were and are still forbidden by the embargo, which can only be lifted by an act of Congress.

If Congress lifts the embargo while Pernod bides its time, the law would also be a likely venue to settle claims dating back to the Cuban revolution—and potentially revoke section 211, which would dramatically change the French company’s odds in court.

Global pressure

Practically since it was passed, section 211 has been a source of friction for the US. In 1999, the European Union challenged the law on Pernod Ricard’s behalf, receiving a decision in 2002 that it does violate international trade rules—a ruling the US has ignored. That means that each month, US representatives must answer to this failing before the WTO’s Dispute Settlement Body, producing bitter exchanges between US, Cuban, and European representatives.

On Jan. 25, 2016, the US delegation was able to proffer the renewal of Cuba’s Havana Club trademark as a positive development to resolve the case. But, while pleased, neither the EU nor Cuba will be fully satisfied until section 211 is amended. Otherwise, the decision is liable to be reversed by US courts at anytime. Both Cuba and Europe asked that the WTO dispute not be closed until the US changes its law.

US diplomats, long sick of this battle, would be happy to see Section 211 go. And since the provisions have only been invoked in this specific case, it may be difficult for Bacardi to convince lawmakers that section 211 should be continued if the embargo is officially lifted. The changing public opinion in the US that has allowed the Obama administration to push forward what has been a popular policy of re-opening may make it hard to protect Bacardi’s claim.

Cuba libre

But any legislation to lift the embargo remains unlikely while the presidential race is in full force: Republican candidates are signaling loud opposition to normalization with Cuba as part of their critique of Obama. But with the business community deeply supportive of normalization and working to prevent a reversal of the nascent re-opening, it’s possible a bill to lift the embargo comes to the floor after the presidential election in November.

For the Bacardi family, this major step in normalization of relations would be bittersweet. While the lifting of the embargo would no doubt complicate its hold on the Havana Club name, the company noted when the normalization efforts were announced that it “hope[s] for meaningful improvements in the lives of the Cuban people and… we continue to support the restoration of fundamental human rights in Cuba.”

A Bacardi spokesperson said it is still too early to be thinking about plans for selling and distilling rum in Cuba once again, should the status of the embargo change. But in an interview in Cigar Aficionado just a few months before Obama would announce the re-establishment of diplomatic ties, Facundo Bacardi, the family-owned company’s chairman, seemed hopeful for a return to the island.

“Offering the world a Cuban-sourced Bacardi rum—it will happen,” Bacardi said. “When we look at Cuba, to us it’s really not a commercial endeavor. We’re going to do all the commercial things because that’s where we’re from. You never forget where you come from, and for us, we absolutely will be back there.”