On May 30, 2013, I died when I gave birth to my son. If I hadn’t listened to my intuition before going to the hospital, I would have stayed dead.

Most of my pregnancy with my second child, Jacob, was healthy and relatively uncomplicated. But when I was around 20 weeks along, I began to have premonitions that I wouldn’t make it through the delivery. Over the next weeks and months, I often felt as if the whole world thought I was crazy. But my experience taught me just how important it is for patients and doctors to pay attention to their gut instincts.

At 22 weeks pregnant, I began to feel as if my body was hemorrhaging. I wasn’t losing blood—but at that moment, I almost fainted on the spot. I went to the hospital to get checked out. By the time I got there, both my vision and the sensation had passed. Doctors could find nothing wrong.

At the 30-week mark, I told a gynecological oncologist that I was sure I was going to need a hysterectomy when I gave birth. I had reached out to the doctor specifically because I knew I would need a specialist to perform one of the most complex female surgeries in existence.

I told the doctor that I kept having visions of my organs colliding like a lava lamp. As it turned out, there’s a name for that problem—the “placenta accreta,” wherein the placenta merges too deeply into the uterus, causing hemorrhaging and potentially a need for a hysterectomy. It’s life-threatening for both the baby and the mother.

The doctor ordered an MRI so that he would be able to see whether an accreta had formed. If the result was positive, he would be present the day of delivery and perform the surgery under a controlled environment. But the MRI came back negative.

Still, I felt certain that I was in trouble even after the test results were in. I knew I wasn’t crazy. But everyone—including my husband—thought I was.

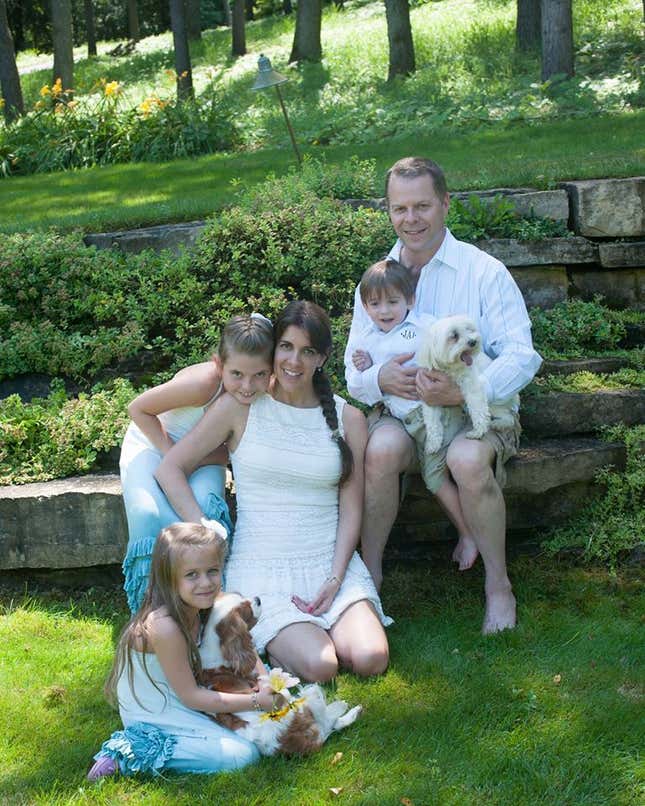

My husband, Jonathan, has a PhD in economics and is a quantitative analyst to the core. So he was comforted by the fact that all of my tests were negative for any signs of abnormalities. “The conditional probability of significant morbidity or mortality is virtually nil,” he’d tell me, sure that this was a wonderfully comforting thing to say. My doctors gave similar reassurances. They’d been trained to trust hard data, and they saw no indication that anything was amiss.

Luckily, there was one doctor who looked beyond the tests and statistics. My ob-gyn recommended that I seek a consultation with an anesthesiologist in preparation for my delivery. During that phone call, five weeks before I gave birth, I explained my visions once again.

Unbeknownst to me, the anesthesiologist on the other end of the line, Dr. Grace Lim, put a note in my file. She did so based on nothing but her own intuition that something might be off. Dr. Lim recommended putting extra blood, monitors and a crash cart in the operating room at the time of delivery. As it turned out, this was the conversation that would save my life.

When I delivered my son, I suffered an amniotic fluid embolism (AFE), a rare complication that affects 1 in 40,000 pregnancies. In these cases, amniotic cells enter the mother’s bloodstream. The mother has an allergic reaction and goes into a type of anaphylactic shock. AFE is the leading cause of maternal death in Australia and Japan and the second-largest cause of maternal death in the United States and the United Kingdom, according to the AFE Foundation.

For 37 seconds, I flat-lined. First came the initial onset of cardiac arrest, followed by my lungs shutting down, bladder collapsing and kidneys failing. Then my body started to lose blood—a lot of it.

The trauma team and doctors at Northwestern Memorial Hospital brought me back to life. And they did so in seconds because they had a crash cart and extra supplies of my very rare blood type—O negative—on hand.

After seven hours of intense life-saving measures, my bleeding continued. The doctors decided that my uterus would have to come out. They called in the gyn/onc with whom I had met with months to perform the hysterectomy. The subsequent pathology on the uterus showed that an accreta had in fact started to form—it just wasn’t detectable on the MRI.

After coming out of a six-day, medically-induced coma, I started on the long and traumatic road to recovery. Then everyone started to ask me: “How did you know?”

I’m still trying to figure that out myself. I understand why human intuition is dismissed as unscientific. But I believe there are good reasons to trust in our “sixth sense”—so much so that even the no-nonsense US military is investigating the power of intuition.

“There is a growing body of anecdotal evidence, combined with solid research efforts, that suggests intuition is a critical aspect of how we humans interact with our environment and how, ultimately, we make many of our decisions,” Ivy Estabrooke, one program manager at the Office of Naval Research, told the New York Times in 2012. The Navy believes that learning to get in touch with intuition could help its fighters to improve their decision-making skills—perhaps saving lives.

Intuition is particularly important in the medical realm, when the issue may literally be one of life or death. Medical humanities scholar Kimberly Myers and radiologist Julie Mack recount how Myers’ conviction that she would be diagnosed with breast cancer, despite having no family history of the disease, helped Mack catch the cancer in a 2013 issue of Atrium, a journal published by Northwestern University’s Center for Bioethics and Medical Humanities. And a 2011 paper published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine notes that while patient intuition can be fallible, just like analytical reasoning, people can also be uniquely sensitive to changes in their own bodies. So it’s important that patients speak up when they feel something may be wrong—and that doctors listen to their own intuition, just as Dr. Lim did in my case.

In fact, Dr. Lim told me that as I was wheeled into the operating room to deliver Jacob, she told the attending physician anesthesiologist, “I have a bad feeling about this.” The fact that she was willing to vocalize that fear may have helped prepare other medical staff to watch closely for signs of trouble.

I’ve reached out to a number of members of the medical community in the aftermath of my experience. Everyone I’ve spoken with says there’s no medical explanation for my premonitions. But some have noted cases in which a patient’s sense of impending doom can be indicative of a future heart attack, seizure or other medical conditions.

With all this in mind, I believe we should put a new twist on the Department of Homeland Security’s familiar maxim: “If you sense something, say something.” What’s the worst that can happen? If your premonitions turn out to be wrong, you haven’t lost anything—except perhaps a little dignity. And if you’re right, trusting your intuition could save your life.