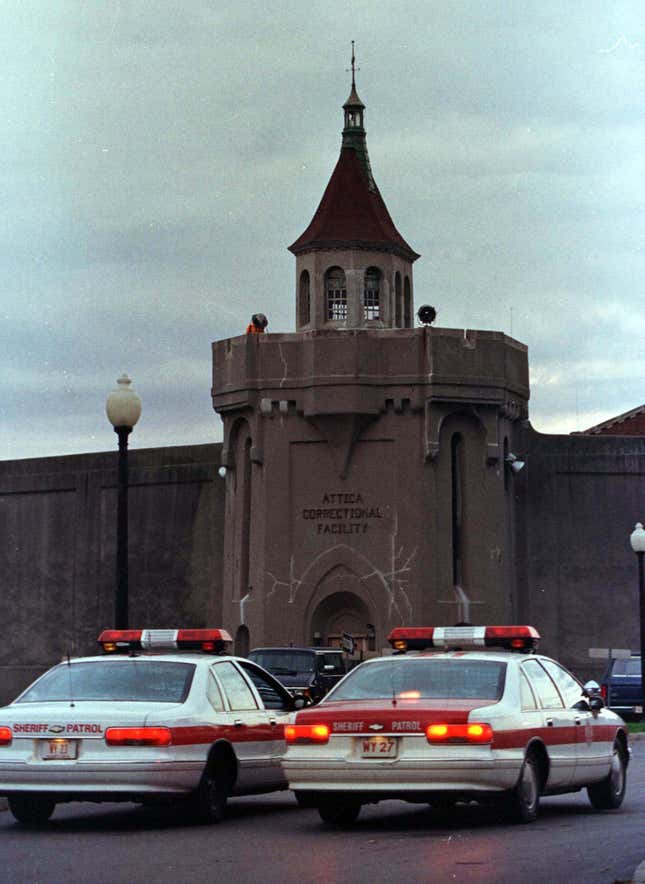

On Sundays, I attend Protestant services at Attica Correctional Facility in New York. It’s my safe place. There’s a band, a choir, clapping, and hands-in-the-air yelling—“Thank you Jesus!” “Hallelujah!” Most prisoners are black with green uniforms, and the guards, posted at the back of the chapel, are all white with blue uniforms.

Reverend Tomlinson, a sixty-something black man from the Bronx who looks forty and wears shiny suits, has kind eyes and a big, bright smile. One Sunday last March, before he began his sermon, the Rev called a prisoner named Steffen Jones to the front of the congregation. Arm around Steffen’s shoulders, he told us that Steffen’s son Tyquan had been shot to death. He was fifteen. We bowed our heads and the Rev led us in prayer.

The writer in me couldn’t help opening my eyes in the middle of the prayer. We were praying to God, asking Him to ease Steffen’s pain, but God knew that we had brought that same pain to so many other parents.

Weeks later, I was facilitating a workshop with the Alternative to Violence Project, a civilian-run volunteer program that began after the Attica prison uprising in 1971. During a break I was talking to a prisoner who calls himself “Paradise,” convicted of trafficking guns and attempting to commit murder with one of them. From behind his big beard and permanent diamond grill, Paradise told me how he used to take drugs from Buffalo, New York, to rural towns in Pennsylvania. After selling the drugs, he’d ask customers with clean criminal records to buy guns for him. Paradise would take the guns back to Buffalo to sell or trade for more drugs.

This is a phenomenon known as straw purchasing, a dangerous loophole that has remained open for decades. I should know, my friends and I had gotten guns the same way in the mid-nineties.

Conventional wisdom holds that if a problem exists—like, say, a loophole that allows untraceable gun purchases–we should just close it. And yet, illegal private-party gun sales account for as much as 40% of gun purchases in the US. Why do we refuse to actually address such a patently—and demonstratively—dangerous problem in American society?

First, apathy. Much of gun violence in America occurs in the self-absorbed world of gangster culture. Recently in the yard I was talking to a nineteen-year-old boy who calls himself “Shots.” He’s serving a sentence of 45 years to life for shooting and killing one victim and wounding another. He told me guns are so ubiquitous in his native Rochester, New York, that he once stumbled upon a nine millimeter handgun while walking in a field of weeds. He took it home. He was twelve.

Some in mainstream culture observe the behavior of incarcerated men like me with apathy: “Let them kill one another,” they say. The reality is some people refuse even to fill out one extra form or wait one extra minute when buying a gun, even if those measures would save a life. But the real apathy exists within the gun lobby. The NRA and like-minded interest groups justify the status quo with red-herring debates and self-righteous interpretations of the Second Amendment. This isn’t about politics, it’s about greed. The wicked irony, of course, is that mass shootings have in the past increased demand and positively effect earnings.

Gun lobbyists are a big part of the problem, and yet there is some truth to that infamous slogan: guns don’t kill people, people do. Surely, some people are always going to do bad things. (Although I also believe those bad things would be harder to commit if guns weren’t so accessible.) There’s a toxic mindset that permeates the counterculture in America’s inner cities and prisons, and it will only end if we create opportunities for the disconnected youth and young adults immersed in this lifestyle. But that will take time and support for the kinds of forward-thinking programs like the one that helped me get my act together.

As I wrote in The New York Times last April, we still have not realized the power of rehabilitation through information. Education in prison changes the lens through which we prisoners view the world, builds our moral fiber, and makes us more employable. All of this positive change will spill over into our communities when we return to them. (And remember, the vast majority of us will eventually return home, at least for a little while.)

Keep in mind, too, that no one will be more impressionable to young aspiring gangsters than seasoned ex-cons. Street cred and intellect is a powerful combination. As for the gun-control opponents who believe gun violence stems from moral decay alone, well, I hope they choose to support the educational programs I describe. Opposing both gets us nowhere.

This isn’t to say some people aren’t trying to make changes. President Barack Obama was right on point when, at CNN’s Guns in America town hall, he told the sobering tale of a van full of straw purchased guns crossing state lines and winding up on the streets of Chicago. But clearly, awareness isn’t enough. We need to investigate individuals who make suspicious gun purchases—like white drug addicts with clean records who saunter into Virginia guns and ammo stores and buy cheap 380-caliber automatics, Taurus 9-millimeters, Tek Nines, and boxes of hollow point bullets—and then file reports claiming those guns stolen before they flip them to criminals on the street.

In fact, there is already a system in place that may be able to help: the e-Trace Firearm Tracing Program, an internet-based tracing program that the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF) already uses. Once e-Trace is programmed accordingly, the Obama administration should provide gun merchandisers with an “Anti-Straw Purchase” memorandum and encourage them to show it to their customers. The memo itself could work as a deterrent by merely making gun buyers aware that e-Trace is investigating straw purchasers—and reminding them that handing guns over to felons is itself a felony punishable by up to ten years in prison. As someone who’s had firsthand experience with these kinds of crimes, I know how easy it is to get spooked.

Unfortunately, there’s no telling how effective these e-Trace investigations will be. The bottom line, though, is that straw purchasers need to be thrown a curve. We need to prevent these transactions from happening in the first place, not implement increasingly stiffer sentences after the fact. I don’t think hefty, new retributive sentencing laws will make a difference.

At the end of the day, if Google and Facebook algorithms can track individual purchasing patterns for the sake of advertisement and capitalism, why can’t the federal government? The Fourth Amendment doesn’t say corporations can pry for profits, and yet they have their way with everyone’s social media accounts. The Second Amendment, meanwhile, does say guns should be “well-regulated.”

There are no easy solutions. My ideas, especially those involving privacy, are bound to make some people upset, especially the ones who romanticize anarchy and the Second Amendment. But what about the people who actually have to deal with the consequences of gun violence every day? Recently, I spoke with a real-life revolutionary at Attica named Anthony “Jalil” Bottoms, a former Black Panther who’s been in prison for the past 44 years for shooting two New York City cops. And though Jalil has a few reservations, on the whole, he agrees that any change that could prevent a gun being trafficked is a good one because it may save black lives That’s important to him. It should important be for all of us.

Which brings me back to the Alternative to Violence Project workshop. On a break, I found Steffen Jones and asked him if we could talk about his son. As it turns out, Steffen is serving 38 years to life for murder and attempted murder. More gangland quarrels; all settled with guns. Stoically, Steffen told me how his child Tyquan was shot in the back of the head as he sat unarmed in a car on a Syracuse street. I told him how sorry I was.

It reminded me of the December night in 2001 when I easily obtained a (straw purchased) assault rifle from a friend and used it to shoot an associate of mine named Alex in the head. He, too, sat unarmed in a car, this one on a Brooklyn street. I killed Alex after learning that he was extorting a man who sold drugs for me. I can’t change what I did even as I feel remorse for it—the responsibility for pulling the trigger is mine alone.

I can’t help but think about what would have happened that night if I hadn’t had access to that gun. Instead, maybe another sequence of events would have unfolded. Perhaps the effects of the Xanax I had taken would have worn off. Perhaps I would have slept on it and felt differently the next day. Perhaps we would have talked it out. Instead, there I was–emotionally empty and angry, and impulsive. Big gun in the trunk. A bit high. It was over in three seconds.

We of this life are engaged in a vicious cycle of hurt—giving it, receiving it. Years ago, I was stabbed six times in a prison yard, and suffered a punctured lung as revenge for killing Alex. Had I been shot six times, I’d be dead.

I can’t speak to the motivations of those who commit crimes repeated ad nauseum on the nightly news. Such mass shootings, like the most recent in San Bernardino, stem from a hate to which I can’t relate. They are not the murders I know. What I do know about, however, are the kinds of murders that happen thousands of times each year. These are crimes committed by men like me, and despite what the NRA may say, at least some of them are preventable.

In June of 2015, nine beautiful people were gunned down after a Bible study at their church in Charleston, South Carolina. The members of Attica’s church are considered some of the most dangerous men in America—and yet it’s my safe place. I’m grateful that God is present in our church to bring out the best in us. I’m also grateful that guns are not accessible to bring out the worst in us.