When my digital media students are sitting, waiting for class to start, and staring at their phones, they are not checking Facebook. They’re not checking Instagram or Pinterest or Twitter. No, they’re catching up on the news of the day by checking out their friends’ Stories on Snapchat, chatting in Facebook Messenger or checking in with their friends in a group text. If the time drags, they might switch to Instagram to see what the brands they love are posting, or check in with Twitter for a laugh at some celebrity tweets. But, they tell me, most of the time they eschew the public square of social media for more intimate options.

The times, they are a-changing

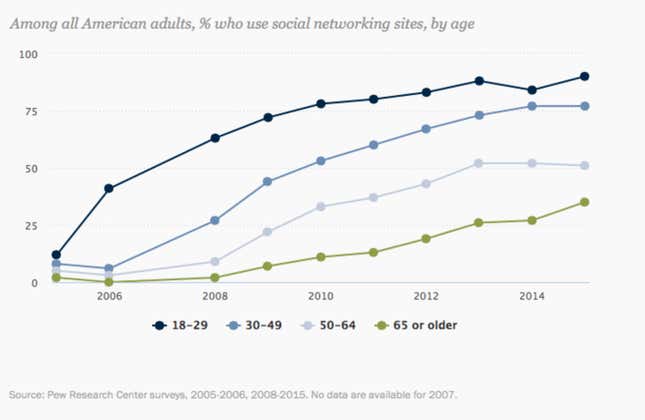

For a few years now, alarms have been sounded in various quarters about Facebook’s teen problem. In 2013, one author explored why teens are tiring of Facebook, and according to Time, more than 11 million young people have fled Facebook since 2011. But many of these articles theorized that teens were moving instead to Instagram (a Facebook-owned property) and other social media platforms. In other words, teen flight was a Facebook problem, not a social media problem.

Today, however, the newest data increasingly support the idea that young people are actually transitioning out of using what we might term broadcast social media—like Facebook and Twitter—and switching instead to using narrowcast tools—like Messenger or Snapchat. Instead of posting generic and sanitized updates for all to see, they are sharing their transient goofy selfies and blow-by-blow descriptions of class with only their closest friends.

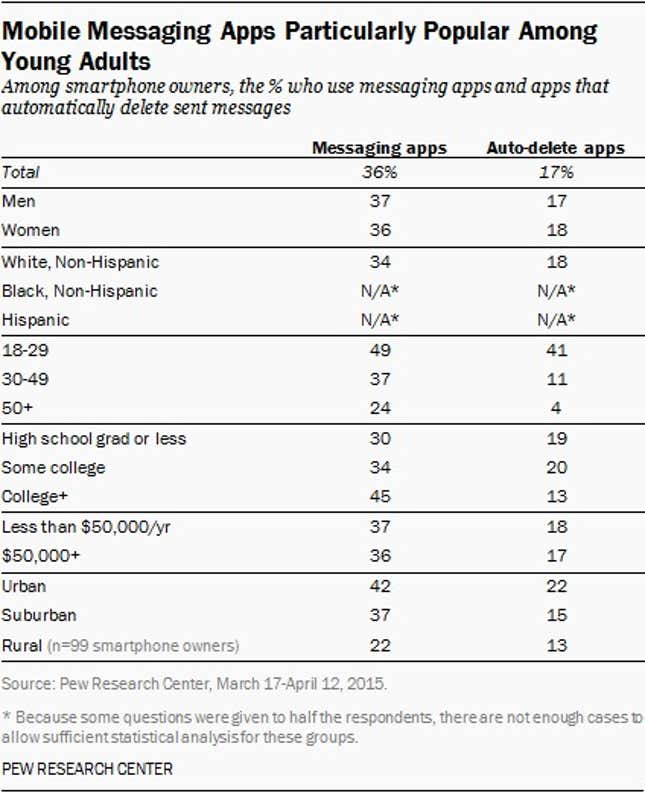

For example, in a study published in August last year, the Pew Research Center reported that 49% of smartphone owners between 18 and 29 use messaging apps like Kik, Whatsapp, or iMessage, and 41% use apps that automatically delete sent messages, like Snapchat. For context, note that according to another Pew study, only 37% of people in that age range use Pinterest, only 22% use LinkedIn, and only 32% use Twitter. Messaging clearly trumps these more publicly accessible forms of social media.

Admittedly, 82% of people aged 18 to 29 said that they do use Facebook. However, that 82% affirmatively answered the question, “Do you ever use the Internet or a mobile app to use Facebook?” (emphasis added). Having a Facebook account and actually using Facebook are two different things. While Pew does have data on how frequently people report using Facebook (70% said at least once a day), those data are not broken down by age. And anecdotal evidence such as what I’ve gathered from class discussions and assignments suggests that many younger people are logging in to Facebook simply to see what others are posting, rather than creating content of their own. Their photos, updates, likes, and dislikes are increasingly shared only in closed gardens like group chat and Snapchat.

Why would they leave?

Although there is not a great deal of published research on the phenomenon, there seem to be several reasons why younger people are opting for messaging over social media. Based on my discussions with around 80 American college students, there appears to be three reasons for choosing something like Snapchat over Facebook.

1. My gran likes my profile picture

As Facebook has wormed its way into our lives, its demographics have shifted dramatically. According to Pew, 48% of Internet users over the age of 65 use Facebook. As social media usage has spread beyond the young, social media have become less attractive to young people. Few college students want their parents to see their Friday night photos.

2. Permanence and ephemerality

Many of the students I’ve spoken with avoid posting on sites like Facebook because, to quote one student, “Those pics are there forever!” Having grown up with these platforms, college students are well aware that nothing posted on Facebook is ever truly forgotten, and they are increasingly wary of the implications. Teens engage in complex management of their self-presentation in online spaces; for many college students, platforms like Snapchat, that promise ephemerality, are a welcome break from the need to police their online image.

3. The professional and the personal

Increasingly, young people are being warned that future employers, college admissions departments, and even banks will use their social media profiles to form assessments. In response, many of them seem to be using social media more strategically. For example, a number of my students create multiple profiles on sites like Twitter, under various names. They carefully curate the content they post on their public profiles on Facebook or LinkedIn, and save their real, private selves for other platforms.

Is this a problem?

We may be seeing the next evolution in digital media. Just as young people were the first to migrate on to platforms like Facebook and Twitter, they may now be the first to leave and move on to something new.

This exodus of young people from publicly accessible social media to messaging that is restricted to smaller groups has a number of implications, both for the big businesses behind social media and for the public sphere more generally.

From a corporate perspective, the shift is potentially troubling. If young people are becoming less likely to provide personal details about themselves to online sites, the digital advertising machine that runs on such data (described in detail by Joe Turow in his book The Daily You) may face some major headwinds.

For example, if young people are no longer “liking” things on Facebook, the platform’s long-term value to advertisers may erode. Currently, Facebook uses data it gathers about users’ “likes” and “shares” to target advertising at particular individuals. So, hypothetically, if you “like” an animal rescue, you may see advertisements for PetSmart on Facebook. This type of precision targeting has made Facebook into a formidable advertising platform; in 2015, the company earned almost $18 billion, virtually all of it from advertising. If young people stop feeding the Facebook algorithm by clicking “like,” this revenue could be in jeopardy.

From the perspective of parents and older social media users, this shift can also seem troubling. Parents who may be accustomed to monitoring at least some proportion of their children’s online lives may find themselves increasingly shut out. On the other hand, for the growing number of adults who use these platforms to stay in touch with their own peer networks, exchange news and information, and network, this change may go virtually unnoticed. And, indeed, for the many older people who have never understood the attraction of airing one’s laundry on social media, the shift may even seem like a positive maturation among younger users.

From a social or academic perspective, the shift is both encouraging—in that it is supportive of calls for more reticence online—and also troubling.

As more and more political activity migrates online, and social media play a role in a number of important social movement activities, the exodus of the young could mean that they become less exposed to important social justice issues and political ideas. If college students spend most of their media time on group text and Snapchat, there is less opportunity for new ideas to enter their social networks. Emerging research is documenting the ways in which our use of social media for news monitoring can lead us to consume only narrow, partisan news. If young people opt to use open messaging services even less, they may further reduce their exposure to news and ideas that challenge their current beliefs.

The great promise of social media was that they would create a powerful and open public sphere, in which ideas could spread and networks of political action could form. If it is true that the young are turning aside from these platforms, and spending most of their time with messaging apps that connect only those who are already connected, the political promise of social media may never be realized.

This post originally appeared at The Conversation. Follow @ConversationUS on Twitter.