A diamond is carbon, one of the most abundant elements on Earth. But as anyone who has ever shopped for, admired, or worn a diamond can tell you, there’s a lot more to them than just a tetrahedal crystalline structure of atoms.

Both physically and culturally, these stones have weight. Diamonds are romance, love, commitment, legitimacy, achievement. Diamonds are forever. But why are they so loaded? Sure, they catch the light, but why do diamonds—rather than, say, emeralds, rubies, tourmalines, or sapphires—get to be a girl’s best friend and everlasting love?

Why? In a word: marketing.

“The diamond dream”

Today, we take sparkling, selfie-worthy, Pinterest page-filling, knuckle-duster engagement rings for granted. But the idea that a diamond’s size and authenticity is directly proportional to the love—and worth—of one’s partner is a relatively new one. It’s the product of an expertly executed marketing campaign staged over multiple years, and it can be attributed to a single company: De Beers.

In its 2014 annual report (pdf), the diamond company explicitly defined its greatest asset—and it wasn’t the $6 billion in rough diamonds its mines produced. Rather, De Beers focused on its commitment to relentlessly nurture and protect an idea— ”the diamond dream”—or, in other words, ”the allure that diamonds have for consumers, based on their association with romance and a sense of the eternal, and the fact that they are seen as a lasting source of value.”

Who dreamed this up?

Forever is a long time. Yet just 100 years ago, diamonds had only just started to trickle into the popular consumer conscience.

Before then, diamonds from India and Brazil were used as an adornment, but only by the ruling classes. Then, in 1866, a teenage boy playing on the Orange River near Hopetown, South Africa found an oddly hard, shiny stone: the 21.25-carat “Eureka Diamond,” that would set off an African diamond rush and transform the market. By the late 1880s, two British mining rivals in South Africa, Cecil Rhodes and Barney Barnato, flooded the market with diamonds as they tried to outsell each other. Prices plummeted, and the men recognized that controlling the supply of diamonds would be the best way to keep prices high. Rhodes took control of Barnato’s company, and in 1888 established De Beers Consolidated Mines Limited.

De Beers proved to be arguably the most successful cartel of the modern era—and after the stock market crash of 1929 hit the demand for diamonds—its savviest marketer.

“South Africa must do without her diamond industry,” wrote the Spectator in February, 1932. “An impoverished world cannot buy its gems; and the diamond syndicate dare not seek more custom by reducing its prices. Diamonds would lose half their attraction if they were cheap. Overproduction of them might spoil the trade for years to come.”

In the 1930s, De Beers already had its hand on the levers of the world’s diamond supply. Now it was time to create more demand.

Enter US advertising agency N.W. Ayer, with an innovative, multi-channel marketing campaign that came to define modern advertising.

Inventing the branding playbook

In 1938, when Harry Oppenheimer, the 29-year-old son of De Beers chairman Ernest Oppenheimer, assessed his options for boosting diamond demand—and prices with it—Europe was on the brink of war, so America became the company’s focus. Oppenheimer partnered with the Philadelphia-based advertising agency, N.W. Ayer, and launched an offensive on the US market.

N.W. Ayer’s researchers found that since the end of World War I, Americans had been buying fewer and cheaper diamonds. De Beers needed to develop demand for bigger, pricier stones. Engagement rings were the perfect vehicle.

Engagement rings had been around for centuries, made of everything from human hair (Victorians) and thimbles (Puritans) to precious metals and gemstones—including diamonds. But diamond-adorned versions were by no means obligatory. Only about one-fifth of brides wore a diamond engagement ring at the end of the 1930s—and the rocks were piddly by today’s standards.

The market was there, it just needed to be re-branded. N.W. Ayer was up for the job, as Edward Jay Epstein chronicled in The Atlantic in 1982:

W. Ayer suggested that through a well-orchestrated advertising and public-relations campaign it could have a significant impact on the “social attitudes” of the public at large…Specifically, the Ayer study stressed the need to strengthen the association in the public’s mind of diamonds with romance. Since “young men buy over 90% of all engagement rings” it would be crucial to inculcate in them the idea that diamonds were a gift of love: the larger and finer the diamond, the greater the expression of love. Similarly, young women had to be encouraged to view diamonds as an integral part of any romantic courtship.

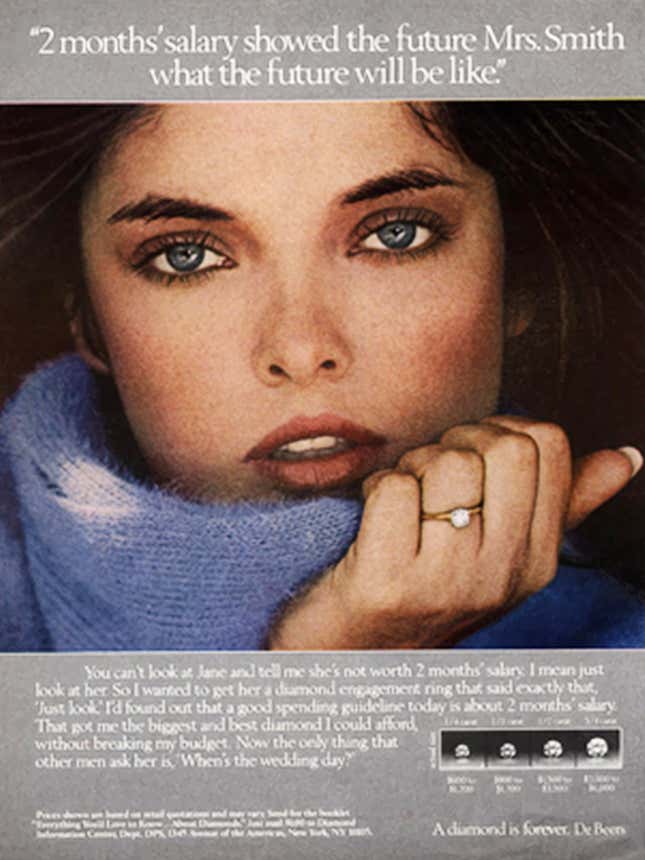

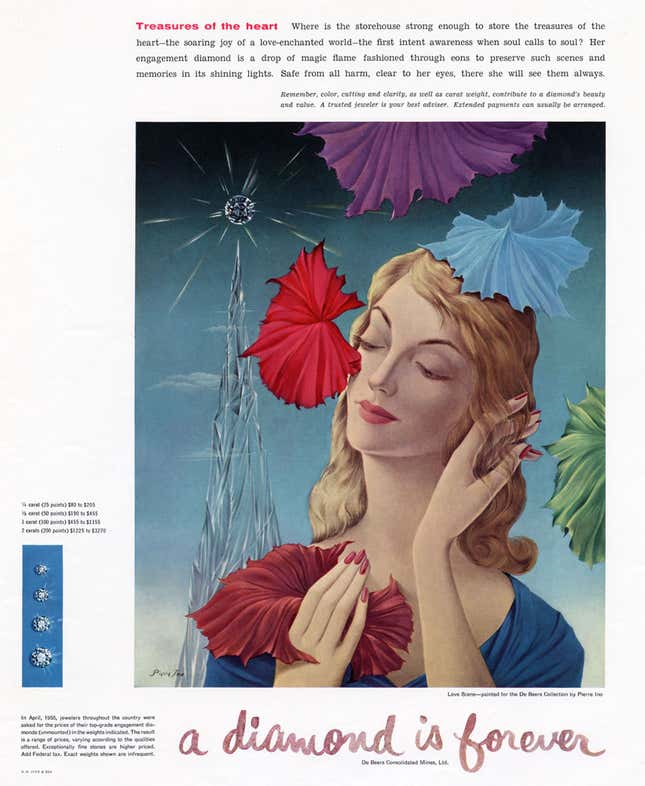

Rather than focusing on sales, N.W. Ayer took the very Don Draper approach of selling an ideal, a concept, a feeling. Ads featured paintings by Salvador Dali and Pablo Picasso, along with poetic copy about the deep significance and singularity of the engagement diamond.

By 1941 N.W. Ayer had already helped increase diamond sales by 55% in the US. More importantly, the agency had planted the seed for “the diamond dream,” laying the groundwork for what can only be described as the most successful marketing campaign of the 20th century.

Forever actually started in 1947

N.W. Ayer’s campaign imbued diamonds with a sense of eternal value. This was designed to not only sell stones, but also to ensure that owners held on to their diamonds. That way, De Beers, which effectively had a monopoly on mining, could control the flow of diamonds on the market, and the price with it.

In 1947, Frances Gerety, a female copywriter (unmarried) who had worked on the De Beers account since 1943, wrote the line that captured exactly the sentiment De Beers needed: a Diamond is forever.

Live from the red carpet

Meanwhile, Gerety’s colleague, Dorothy “Diamond Dot” Dignam launched a stealth marketing campaign to promote the stones outside the traditional realm of advertising. Decades before US Magazine or “Live from the Red Carpet,” Dignam wrote a monthly newsletter to the media, helping to plant stories about which Hollywood stars wore diamonds, and how integral the stones were to their courtships.

Today, it’s commonplace for celebrities to walk the red carpet in borrowed jewels—and namecheck the brands: Van Cleef, Tiffany, Cartier, and so on. But without Dorothy Dignam and De Beers before them, Harry Winston’s PR department might never have seen the opportunity in draping Jennifer Lopez with 200 carats of diamonds, giving women something to aspire to.

Surprise!

For decades, N.W. Ayer’s research findings would prove invaluable to De Beers, and by extension, the diamond industry as a whole. Many of the marriage proposal elements we think of as traditional, and quintessentially romantic, are actually products of De Beers advertisements. (Sorry!) For example, Ayers’ research found that unexpected diamond gifts were not only thrilling for women, they also freed them from feeling guilty about their partners’ purchases.

And as Anne Kingston writes in The Meaning of Wife, studies also showed men spent more when they shopped alone (as opposed to with their sensible partners). Surprise became an integral part of DeBeers’ diamond dream.

Exporting the diamond dream

Over N.W. Ayer’s first four decades of service, between 1939 and 1979, De Beers’ wholesale rough diamond sales ballooned from $23 million to more than $2.1 billion, and the diamond engagement ring was established as a new marker of American life.

In the 1960s, De Beers took the show on the road, targeting the Japanese market with the help of agency J. Walter Thompson. In Japan, diamond rings had no place in a tradition of arranged marriages. As Epstein writes, J. Walter Thompson created a series of ads that linked diamond rings with “modern western values,” with great success. In 1967, the campaign’s first year, less than 5% of engaged Japanese women received a diamond ring. By 1981, 60% did, making Japan the second-largest market for diamond engagement rings after the US.

The diamond dream goes global

The US is still the largest consumer of diamond jewelry, and now, De Beers and its rivals in the industry are turning to emerging middle classes to develop the diamond dream. In China in the 1990s, engagement rings were nearly non-existent; In 2013, nearly one-third of brides received them.

In India, the third largest market for diamonds, De Beers noted the majority of marriages are arranged.

“The true ‘Love’ acquisition route starts for Indian women after the wedding, mainly through the celebration of wedding anniversaries,” wrote De Beers in a 2015 report.

Has the diamond dream outshined the diamond?

Although De Beers isn’t the superpower it once was, the company still supplies a huge portion of the world’s rough diamonds, accounting for over a third of the market (pdf).

Today most brands have taken a page out of De Beers and N.W. Ayers’ multi-channel, psychological, category-defining marketing playbook—so much so that in some cases, brands themselves have superseded the products they set out to sell.

A 2013 McKinsey report (pdf) noted that jewelry consumers increasingly prioritize brands when shopping—a trend the consultancy expects to continue into the future. “Consumers will want ‘a Tiffany ring’ rather than ‘a diamond ring,” it says.

My hunch: They’ll want both.