Cape Town, South Africa

When you look at a profile on LinkedIn you see a job title, a set of skills, a resume with a list achievements. Though the social platform is based around connections, it still focuses on employment in a traditional way. What’s more, it doesn’t require face-to-face interactions.

In 2011, a UK social enterprise named Participle launched a two-year prototype of a career-building program called Backr, which focused on relationships not skills.

Hillary Cottam, founder of Participle and speaker at this year’s Design Indaba conference in Cape Town, wanted to approach work from a different starting point. Typically, the unemployed or underemployed—people who need networks the most—don’t have access to them. Most jobs aren’t advertised (paywall) and what’s crucial is learning how to build relationships.

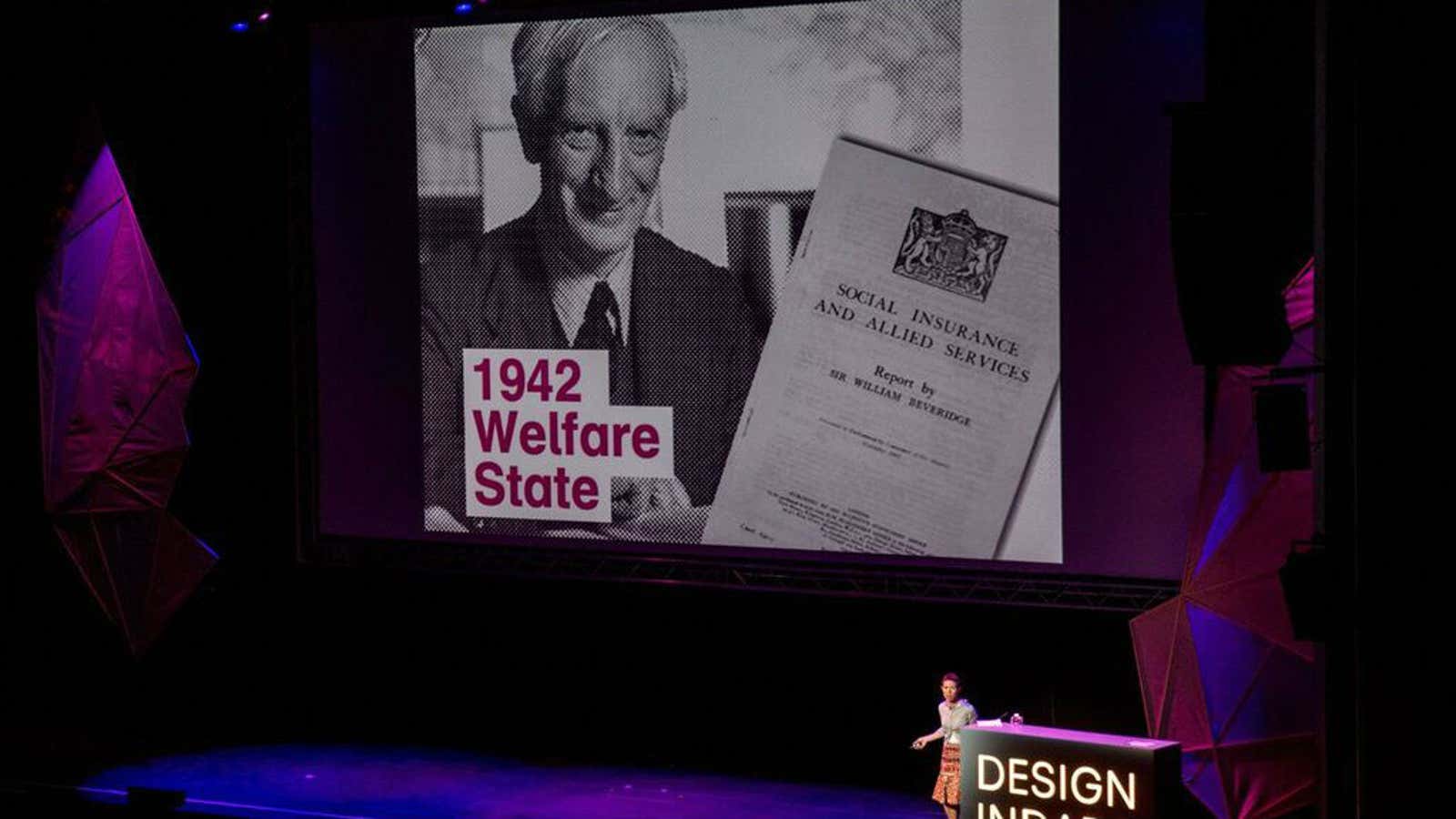

In her talk at Indaba, Cottam looked back to British economist William Henry Beveridge, who is known for his 1942 report “Social Insurance and Allied Services,” which shaped decades of social services in the UK. At the end of his life, Beveridge realized that his model addressed the structural problems, but left out one fundamental ingredient: the people.

Instead of making the same mistake, Cottam said it was integral for Backr participants to overcome “personal challenges” like obtaining childcare, building confidence, or making the leap to venture into a new part of town. Iteration was key and technology enabled the service to scale.

This is how the program worked: the government job center referred people who could opt-in to Backr. The service regularly called members, offered coaching sessions, and most importantly, pooled a mix of people who were employed, in-between jobs, and unemployed.

After two years, an independent evaluation by PricewaterhouseCoopers found the following about participants: 81% reported an improvement in confidence; 87% felt some or strong progress toward employability; 53% moved into some level of work. Financially, it made sense, too. Rather than working with individuals like a job center does, the Backr program lowers its average cost by having members work together.

Cottam is passionate about reinventing traditional business models and changing systems, not just pushing out her projects, though she told Quartz that an organization in New York is interested in using the Backr model.

Quartz spoke to Cottam about what she learned from Backr and how she envisions the future of work. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

For Backr, you said it’s really important ”the community includes people in work, out of work, and in between work.” How do you ensure that happens?

Our services are curated, we can’t just let it happen. We have to put a lot of work into encouraging people who have a lot of skills. I don’t really like to say it this way, but at the “top end and the bottom end,” we have to curate the service. We have to ensure that people who really need help—we encourage them in, and we have to ensure that people who have skills to give come in. But one of the things about people who have skills to give, the way that the labor market is changing, there are a lot of people in middle management jobs who need a lot more experience managing people to progress in their career. So this is a brilliant thing for them. They can come in, they can coach other people and they can use that in their own profile on LinkedIn or wherever to show this experience and that helps them move up.

How do you incentivize the people who are well-employed to participate?

Partly it is that a lot of people are getting skills to progress in their career but also people just want to give their time. People ask me this question for all of our work. You know we built this youth service that was entirely dependent on the community stepping up and working with young people. We worked with two local authorities and they said, “This will never work.” So we said, “Well, can we try?” In these two locations we went around to 100 businesses a day and we said, “Would you have a young person work with you?” Almost everybody we asked said yes. People are never asked.

One thing is that people are never asked and the second thing is that technology makes it simple. Let’s say you’re a busy person and you’ve got a great job, you live in Manhattan, so you’re probably not going to sign up for every Thursday. But you might say, “Over a month, I could spend one night a week. Wednesdays are generally better than Tuesdays.” Then we can kind of match your profiles. We’re able to use very small amounts of time, according to what people have.

Where does your revenue come from?

Our revenue came from local authorities, the local government, who have a statutory duty to basically support people into work.

So they’re outsourcing their job to you?

Yes. The idea would be, in a logical, sensible world, you do this work with thousands of people and you show how cheap it is. You have an independent body do an evaluation from somebody like PricewaterhouseCoopers that everybody trusts. Then everyone says, “Wow, so this is much better. Why don’t we stop doing this and start doing that?”

It just isn’t that simple—it’s politics. And at the moment, nobody in Britain wants to upset the unemployment system. The only way for us to work is to build a parallel system funded by local authorities rather than remove the existing system.

What are you interested in now, in terms of work?

I’m really interested in modern work. How do we create good work? In Britain, we have this things called “shit jobs.” What you get is a shit job; you have no prospects; you’re still living on benefits to keep your family alive; it’s not interesting. You’re treated like shit. I’m interested in how business, government, and people come together to resolve those problems in the 21st century. I don’t think these problems are good for business or society and I think that enlightened business realizes this already.

What do you think about the changing way that a new generation of young people want to work? In terms of telecommuting, flat hierarchies, and not having a job for life?

I think that is the future and what we need to do is build support around people in that kind of labor market. I think it’s fantastic, but you’re very vulnerable. For example, in Britain we have a society where you need to buy a home; it’s not great to rent. But all the financial packages for buying a home are built around having a job with a salary that can underpin your mortgage. So there are all kind of issues around safety nets for the millennial generation. I’m really interested in how you make this fantastic.