Shortly after I became engaged, my family members began to worry aloud about the health of my future husband. You see, my fiancé Ray is a man—and he’s about to marry a pescatarian.

While it’s true that I don’t eat meat, I also have no plans to throw myself in Ray’s path if he wants to fix himself a burger. Yet my grandmother, cousins, and even my sister all seemed to assume that under my influence, he would wither away on a steady diet of fruit, vegetables, fish, eggs, cheese, grains and legumes.

To be fair, this is a pretty standard assumption. In the US, at least culturally speaking, we still seem to believe that men need meat. There’s just one problem: The close association between masculinity and meat is literally making men sick.

Until this year, US government guidelines supported the idea that meat was—if not manly—at least a staple of a healthy diet. But in January, US dietary guidelines broke with tradition. Buried many pages in the dense federal document was a caution directed at men: “Some individuals, especially teen boys and adult men, also need to reduce overall intake of protein foods by decreasing intakes of meats, poultry, and eggs and increasing amounts of vegetables or other under-consumed food groups.”

It’s clear that too much meat takes a toll on our health. High meat consumption has been linked to a long list of health problems, from cancer to weight gain to kidney problems and cardiovascular disease. But most men eat twice the amount of the protein they need. In 2011-2012, for example, American men between the ages of 30 and 39 ate an average of 110 grams of protein, according to US government data. That’s roughly double the 56 grams the government currently recommends for men. (American women in the same age group ate an average of 75.5 grams of protein, also higher than the government-recommended amount of 46 grams.)

How did it come to be this way? In terms of nutrition, there’s little meat has to offer that other food groups don’t. The meat industry likes to tout the high iron and B12 counts in animal protein. But iron is found in plenty of vegetables and beans, and B12 is available in dairy and eggs as well as vegan foods such as alternative dairy products and nutritional yeast. And studies regularly tout the health benefits of a vegetarian diet, connecting it to a reduced risk of heart disease, cancer, and Type 2 diabetes.

Yet the connection between manliness and meat-eating shows up everywhere in contemporary culture: in Carl’s Jr. commercials featuring a swimsuit-clad Paris Hilton, selling sex and burgers all in one go; in the pages of Men’s Health magazine; and in teasing depictions of Ron Swanson, that paragon of mustachioed masculinity, downing endless amounts of ribs, steak, bacon, and something called a meat tornado.

The idea that men need meat is a very old one, as Carol J. Adams argues in her seminal 1990 book, The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory. She traces these anecdotes all the way back to the Bible, when the Book of Leviticus chronicled how sacrificial meat was cooked only for the priests and sons of Aaron.

This patriarchal prerogative for meat extended into the 20th century. During World War II, the entire American nation cut its consumption of meat (along with sugar, butter, and a host of other supplies) so that the men in the army wouldn’t have to. The same global phenomenon was heavily documented in the 1960s and 1970s. In Indonesia, Frederick J. Simoons wrote, “flesh food [was] viewed as the property of the men.” In Ethiopia, women prepared two meals: One with meat for men, and one without for women, according to Lisa Leghorn and Mary Roodkowsky’s Who Really Starves: Women and World Hunger.

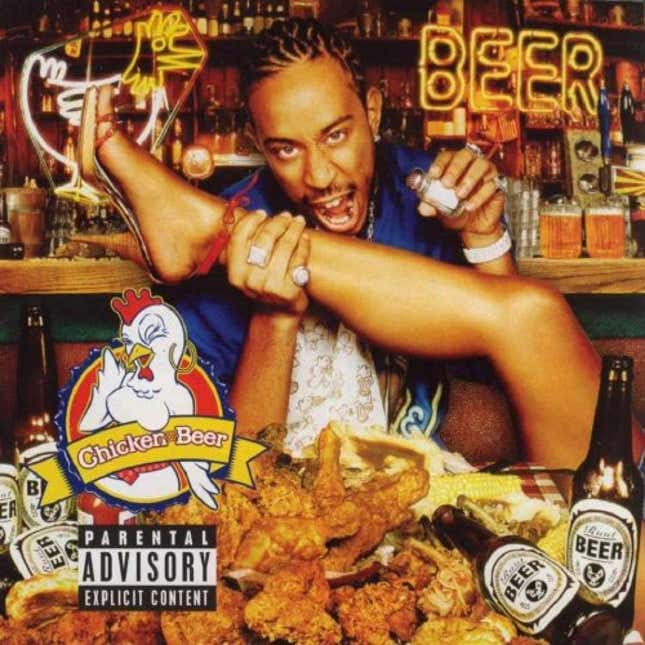

The link between masculinity and meat has been further reinforced by the sexualization of meat in popular media. The aforementioned Carl’s Jr. commercial featuring Paris Hilton is only one in a long line of images that equate women with meat. A 1981 photo from parody lad mag Playboar features Ursula Hamdress, a masturbating, panty-clad pig. The cover of Ludacris’s 2003 album Chicken-N-Beer shows the rapper surrounded by chicken, ready to bite into a woman’s leg. A federal judge in 2008 was revealed to have posted photos online of naked women painted like cows, standing on all fours.

All this does a disservice to both men and women. The message embedded in the sexualization of meat is that women, like chicken and steak, exist to be salivated over and consumed by men. And making meat consumption seem necessary to achieving full manliness also encourages men to overindulge—a behavior we now know to be unhealthy.

With these kinds of cultural connotations, it’s unsurprising that the business of meat is dominated by men at the top, as a meat industry veteran and contributor to the industry publication Meatingplace pointed out in November of last year. “I did a brief survey and found that of the top eight beef and poultry companies, only one had any women close to the top of the food chain in their corporate structure and none serving as CEO,” writes Mack Graves. He notes that women still do the bulk of the grocery shopping in the US. So why aren’t meat companies hiring more women to sell their products?

It’s a fair question, so I asked the North American Meat Institute, the trade association representing companies that process 95% of red meat and 70% of turkey in the US. At the very least, I expected to hear about the efforts being made to improve those numbers, as is common in other male-dominated industries such as tech, law, and medicine. Instead, when I asked about the lack of women in leadership roles, a spokesperson told me: “I’m not sure why you would be covering a marketing consultant’s blog.”

While women don’t hold many upper-level positions in the meat industry, their representation is much higher in meat, poultry and fish processing plants, according to the Department of Labor—close to 35%. These are the meat industry’s most dangerous jobs, with injury rates more than 17 times higher than that of the rest of the American workforce.

The upshot: Despite eating less meat, women still bear many of its costs—whether by braving dangerous work conditions in its packing plants, devoting money and time to buying and cooking it, or taking on caregiving duties as diet-related illnesses continue to rise. Meanwhile, women reap few of the $95 billion industry’s rewards.

Thankfully, the new dietary guidelines may be a harbinger of positive changes to come. Some of the most visible faces of the plant-based diet movement are now men. Josh Tetrick, co-founder and CEO of vegan mayo startup Hampton Creek, and Beyond Meat founder and CEO Ethan Brown are two highly visible—not to mention manly—entrepreneurs in the increasingly hot world of plant-based startups. Vegan politicians, including New Jersey senator Cory Booker and former president Bill Clinton, are also helping to destigmatize plant-based diets for men. And male doctors, athletes, and firemen dominate the pro-vegan documentary Forks Over Knives, all of them lauding the benefits of foregoing meat.

As a feminist, I’m tempted to defend what’s typically a woman-dominated domain from male encroachment. But as an advocate for health, animal welfare, and the environment, I say: Welcome. Have some hummus.