Facebook boss Mark Zuckerberg lectured mobile phone operators gathered in Barcelona yesterday about their obsession with faster 5G connections for “rich people.” And indeed, a Pew survey on global internet use (pdf) released yesterday (Feb. 22) shows that there’s still a pervasive gap in the use of mobile and internet technologies between rich and poor countries, even as use of these technologies is increasing across the board.

But it turns out that the digital divide isn’t just about money. A study released by Facebook (pdf) yesterday points out that another major adoption barrier is the fact that the internet is dominated by a handful of languages, creating an exclusionary and irrelevant network for people who don’t speak those tongues. “Just 10 languages account for 89% of websites (56% are in English),” the Facebook report says.

While factors such as affordability, the availability of infrastructure and education levels are still significant, the linguistic exclusion reinforces the irrelevance of the internet to many. “The internet produces content to meet the needs of those already connected,” the Facebook report says. “In the absence of intervention, people who already use the internet will be the ones to shape its destiny, and the gap between the connected and unconnected will only grow deeper.”

One measure of linguistically relevant content on the internet is the number of “encyclopedic” articles available online. By this measure, nearly 60% of the world’s population has access to more than 100,000 Wikipedia entries in their mother tongues, or roughly the same number of entries contained in the online version of the Encyclopedia Britannica. That covers 55 languages.

But only speakers of 12 dominant languages get to experience the sheer breadth of Wikipedia, with more than a million articles available. This represents just a fifth of the world’s population.

It’s not just the content held in apps or websites that exclude many languages. The apps themselves, and the operating systems, need greater linguistic diversity. Taking Google’s Android 6.0 smartphone operating system as a benchmark, the Facebook study found that most of the developed world had their mother tongues covered. But in the developing world just 61% of the population would find a version of Android localized to their language.

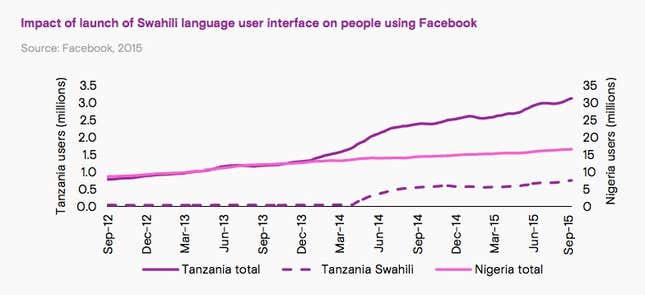

When localization does happen, there’s a rapid uptick in user growth, as Facebook discovered in Tanzania. It added a Swahili language user interface to Facebook there in March 2014, and proceeded to triple its user base within a year.

To be sure, the tech giants are working on getting their services rendered in a broader set of languages. And it’s easy to see why they would get behind an effort towards multilingualism: The more users, the better for their bottom lines.

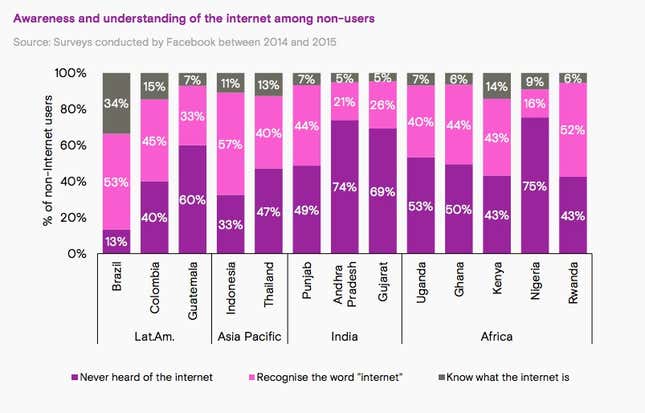

But language remains one of the major four barriers people face when getting online, according to Facebook’s report. There’s also the fact that offline populations often don’t know what it is we’re all babbling about when we talk about the internet. In Nigeria, a Facebook survey found that 75% of respondents had never heard the word “internet” before. The Indian states of Andhra Pradesh and Gujarat showed similar results.

Even as tech companies roll out low-cost plans to bring people in developing countries online, that disconnect remains evident—when new users, for example, don’t realize they’re on the internet when they use Facebook, as a Quartz-commissioned poll found in 2015.