A tentative ceasefire between warring parties in Syria is set to come to force on Saturday (Feb. 27), but the international community remains skeptical that it will hold. John Kerry, the US secretary of state, has warned that if the ceasefire fails, the US might have to consider a Plan B—namely a partition of Syria.

“This can get a lot uglier,” Kerry told the US Senate’s Foreign Relations Committee.“It may be too late to keep it as a whole Syria if we wait much longer.”

It’s the first time Kerry has spoken publicly about partition—which he is not yet advocating—but there have been plenty of murmurings of this so-called last-ditch solution.

Israel has expressed similar doubts that the ceasefire will hold. Defense minister Moshe Ya’alon suggested that Syria is “going to face chronic instability for a very, very long period of time” that could result in a number of enclaves, such as “Alawistan,” “Syrian Kurdistan,” “Syrian Druzistan,” and so on. Ram Ben-Barak, director-general of Israel’s Intelligence Ministry, went as far as to describe partition as “the only possible solution.”

Some suggest a partition plays into Russia’s hands (paywall); Britain has accused Russia of trying to carve out an Alawite mini-state in Syria.

As countries interested in protecting their own interests consider carving up Syria, the history of partition in the region highlights the problem with dividing people along ethno-religious lines.

Syria is no stranger to partition

This year marks the centenary of the Sykes-Picot agreement, where Britain and France secretly split up the Arab provinces of the Ottoman Empire between themselves after World War I. Iraq, Transjordan, and Palestine came under British influence, Syria and Lebanon under French power.

But the preliminary divisions in this treaty highlight the problem of dividing people by sectarian affiliations. For example, the proposals envisioned Lebanon as a haven for Christians and the Druze, while Syria was to be a place for Sunni Muslims. As political economist Tarek Osman points out, these secretion divisions weren’t necessarily a reflection of reality on the ground.

The French and British employed the colonial policy of divide-and-rule for their own economic and ideological purposes. Some go as far as to blame the Sykes-Picot agreement for the current problems in Syria, and the rest of the Middle East, today.

“The artificiality of state formation has caused numerous conflicts over the last few decades,” Henner Fürtig, director of the Institute of Middle East Studies at GIGA research institute in Hamburg, told Deutsche Welle. “These questions haven’t been solved for a century and burst open again and again, in a cycle, like now with the ISIS advance in northern Iraq.”

These divisions would later be quashed under anti-colonialist struggles, which called for a united Arab world against imperialist powers, and then later brutally suppressed in the 1980s and 1990s by what Osman describes as the “Arab world’s strong men,” including Hafez Assad, Saddam Hussein, and Muammar Gaddafi. Osman argues these cracks and divisions didn’t disappear, they came to the forefront at 2011 Arab Spring uprisings.

Ayse Tekdal Fildis, assistant professor in the Department of Political Sciences at Halic University in Istanbul, also blames artificial divisions imposed by French imperialists, arguing: “The process of political radicalization was initiated during the era of the French mandate, the legacy of which was almost a guarantee of Syria’s political instability.” CNN’s Fareed Zakaria used this argument to explain why Syria is imploding, and why Western powers should stay out of Syria.

Others are less convinced with the argument that those borders are the sole factor for the political instability in Syria today.

Sarah El Sirgany, a journalist and fellow at the Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East, told al-Jazeera that “to trace every event, mishap, war, conflict or even agreement back to the Sykes-Picot agreement would be giving it more than it deserves.” She argues a lot has happened since then, governments have been overthrown and world powers have shifted, while others point to other treaties as important contributing factors.

Who will own what?

Advocates for partition point to the relative success of the Dayton accords in 1995, which formally ended the three-and-a-half year war in the Balkans. Leaders of Bosnia, Serbia, and Croatia signed an agreement that preserved Bosnia as a single state, but divided it into two parts. The accord created a federal system; the Muslim-Croat federation would represent 51% of the country, while a Serb republic would hold the remaining 49%.

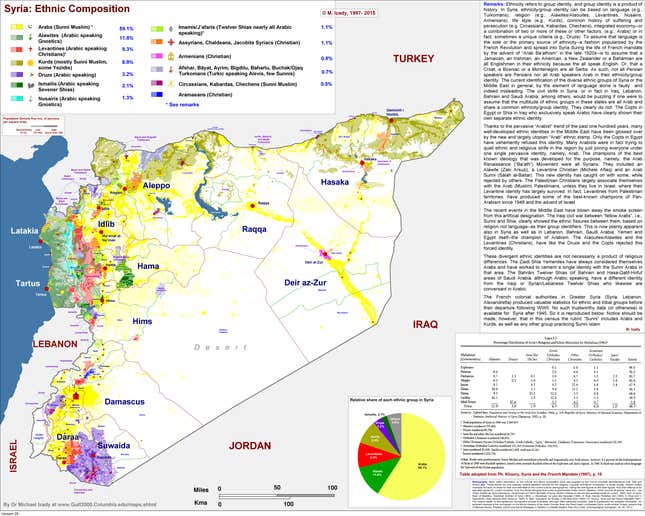

More than 200,000 died before the peace deal was reached. Bloomberg columnist Marc Champion, who describes the Dayton as an “imperfect solution” to end the bloodshed, calls for a similar temporary partition of Syria. A map created by Columbia University’s Gulf/2000 Project shows how difficult that could be. Each color represents different groups in Syria, which at times overlap.

Critics warn that a partition of Syria could require the mass displacement of different ethnicities, which could to the kind of horrors during the India-Pakistan partition.

The 1947 partition of colonial India divided it into two separate states; Pakistan, with a Muslim majority, and India, with a Hindu majority. Thomas Carlson, assistant professor of Middle Eastern History at Oklahoma State University, points out that “around 15 million Hindus and Muslims were on the wrong side of the line and were forced to flee for their lives. Hundreds of thousands were killed.”

These borders do not always last. The artificial state of Pakistan could not hold, with isolated East Pakistan becoming Bangladesh in a bloody war of independence. The border between Iraq and Syria, established by Sykes-Picot, lasted a long time—from when when it was created until ISIL established its own so-called Islamic State connecting large areas of the two countries in 2014. The Kurds have had their own autonomous region in Iraq since the US invasion in 2003.

The lessons of past partitions suggest those who have the most to lose are minority groups who don’t wield significant political power. While finding peace in Syria is proving to be very hard, dividing people by ethnicity or sectarian affiliation is no quick fix in the long run, either.